No Bridge of Agreement

Citizens, Celebrity Weigh In on Suicide Barrier; Councilmembers Ask for More Transparency

Attorney Marc Chytilo wasn’t impressed by Caltrans’s public meeting last week on the proposed suicide barrier for Cold Spring Bridge. “It was hugely overstaffed and overproduced,” he said, estimating the agency spent $15,000-$20,000 on creating “elaborate presentation materials” and bussing in nearly a dozen staffers. “They had their posters in frames,” he chuckled.

Chytilo — representing members of the anti-barrier group Friends of the Bridge, who contend a blockade would ruin the span’s panoramic view of the Santa Ynez Valley — successfully sued Caltrans into reworking and recirculating its report on the nine-foot, seven-inch fencing that would line the historic steel structure. The proposed mesh wall is meant to prevent any more people from leaping off what has become a magnet for those wishing to take their own lives in Santa Barbara County. Fifty-four have jumped to the rocks below since 1963.

Chytilo argued that the state transportation agency’s original 2009 Environmental Impact Report (EIR) failed to properly address the visual and cultural impacts such a barrier would have on the bridge, and that the public wasn’t given the opportunity to weigh in on the project. Judge Thomas Anderle agreed, and ordered Caltrans to stop work in July until a supplement to the EIR was vetted by Santa Barbara residents and then resubmitted for approval. A 52-year-old man jumped the same week workers halted construction.

When confronted with Chytilo’s complaint, Caltrans spokesperson Colin Jones was exasperated and incredulous. “We take the judge’s ruling very seriously,” he said, admitting Caltrans didn’t do a good enough job on its original EIR but promising the agency is committed to getting it right this time around in order to stop people from “using the facility to kill themselves.”

Jones explained that the reason a significant amount of money and resources were devoted to the meet-and-greet forum — numerous informational placards, interspersed with suited Caltrans reps, encircled the interior of San Marcos High School’s cafeteria — was to satisfy the judge’s decision and let citizens learn about the proposed barrier in a mellow, nonconfrontational format. “You do too little and people complain, then you do too much and people complain,” he said. “You can’t want this and then criticize it when you get it.”

The hundred or so residents who showed up, he continued, were a testament to the event’s success. People tend to offer their opinions more openly when they can submit their comments in writing, he said, or privately with a court reporter, instead of facing a panel and crowd.

While Chytilo feels Caltrans went too far above and beyond, some members of the Santa Barbara City Council said there still isn’t enough transparency to Caltrans’s tune. Councilmembers Dale Francisco and Frank Hotchkiss will ask their colleagues during today’s council meeting to support a request that Caltrans provide precise engineering specs of Cold Spring Bridge so that they can better understand why a safety net alternative isn’t even an option.

“We hope that City Council will express its support for transparency in the interest of creating a true public consensus,” they wrote in a memo sent to City Administrator Jim Armstrong and other members of the council. Francisco and Hotchkiss also said that there’s no reason to release any figures to the public at large; specs would only need to go to State Historic Preservation Officer Wayne Donaldson, who’s worked with engineers on the submitted proposals.

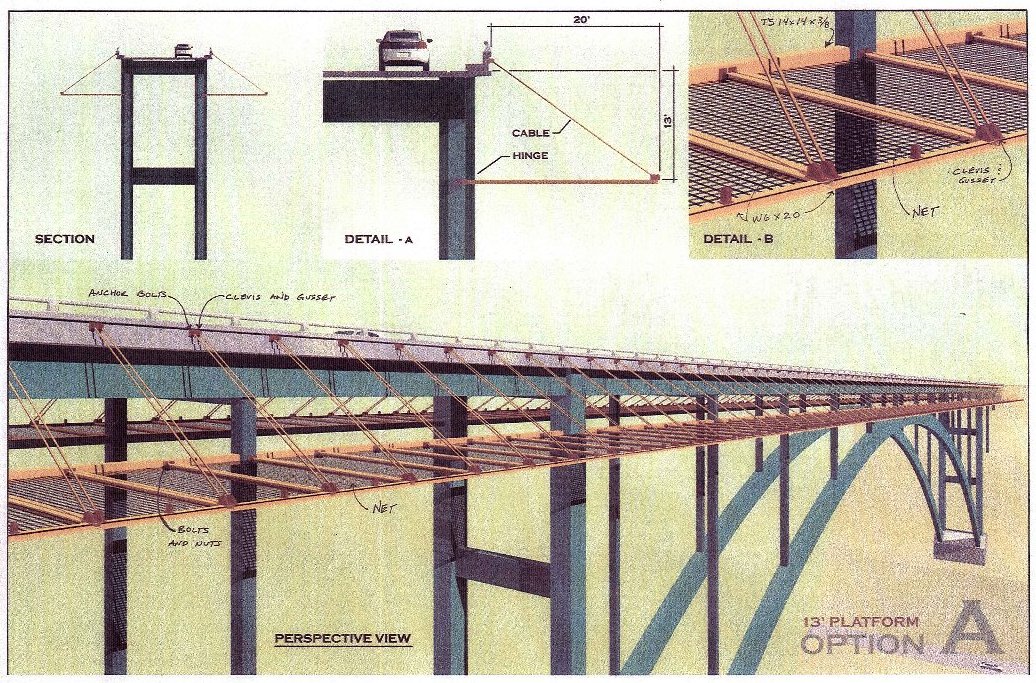

In its supplement to the original EIR report, Caltrans essentially nixed the possibility of installing a net below the bridge designed to catch jumpers. It argued that five net variations — all placed 13-20 feet below either side of the bridge, beneath the pedestrian walkways — were “ultimately withdrawn from consideration” for a number of reasons:

It’d take too long for rescue crews to reach someone who fell into the net, meaning they’d have time to recover from the stun of the original impact, make their way to the edge, and jump again. Emergency personnel would also be subject to “unacceptable risk” when plucking jumpers from the net, potentially dealing with a “distraught, uncooperative, or violent” individual while teetering 400 feet above the canyon.

The net would also act as an “attractive nuisance,” argued Caltrans, potentially luring thrill seekers. It’d also “diminish the integrity of the historic structure” by permanently altering its appearance and cost too much to put in and maintain. Lastly, and most importantly, Caltrans said Cold Spring Bridge simply can’t accommodate a net alternative because of the structure’s design load limitations.

The EIR supplement, though, intentionally omitted any specific data on this last point because of “sensitive public safety and security issues pertaining to Homeland Security, which have been in place for several years well before a suicide barrier was proposed,” said Jones in a statement.

Marc McGinnes, a lawyer and former UCSB professor who now heads anti-barrier group Friends of the Bridge, doesn’t buy it. “Caltrans was wrong before,” he said, claiming the agency has already made up its mind and is finding any excuse to push the fence barrier proposal through. “We have learned enough not to take their word on it,” he said.

McGinnes and others contend a net below the bridge would preserve “years of viewing time” for the 16,000 people that drive across it every day, and save lives at the same time. And McGinnes said when it comes to building a barrier, money should be no object and Caltrans shouldn’t use the additional cost as an excuse. “It’s a world-renowned bridge,” he said. “Spend the money.” The project’s price tag, growing larger every time its delayed, is currently hovering above the $3 million mark.

Central to McGinnes’s argument for a net alternative is news that San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge is moving closer and closer to putting one in place to catch the average of two dozen people who jump off that span each year. If it works for the Golden Gate, McGinnes argued, it should work for Cold Spring Bridge. Chytilo agreed, explaining that the net alternative for the Bay Area span faced the same challenges and criticisms but has so far been able to overcome them.

Like McGinnes, Chytilo thinks Caltrans isn’t looking hard enough at all the options, and is pushing the fence barrier without providing all the facts. “It was clear from [Wednesday’s] materials that Caltrans has already made a decision,” said Chytilo, elaborating that the Sheriff’s Department — which supports the fence option — is being similarly, prematurely dismissive.

Lt. Darin Fotheringham, in attendance last week with a few other department representatives, said the preferred mesh fencing design is a good one and that he doesn’t think a net would be as feasible or practical. In its EIR supplement, Caltrans explains that the fence’s in-curving grid panels would have two-inch square openings that’d make it hard for anyone to secure finger- and toe-holds. And the steel itself, the agency writes, would be coated with a low-reflectivity finish to help reduce glare and “allow the grid/mesh to recede visually.”

The other barrier option — called the Vertical Picket Alternative and characterized by a row of thick steel rods — wouldn’t blend with the background as well and would “result in the barrier itself being more noticeable,” writes Caltrans. Regardless of the final design, Fotheringham said, it’s imperative a fence be put in place soon. Some of his most hair-raising moments on patrol duty, he explained, were on the bridge. “It’s flat-out scary,” he mentioned regarding the two-foot, seven-inch railing now in place. He also spoke about his experience of recovering bodies, explaining that the instances when he had to deliver death notifications to surviving family members still haunt him.

Responding to those who say no barrier is acceptable — that any such addition to the bridge would be detrimental to its grandeur and history — Fotheringham said the benefit would far outweigh the impact. He opined that while there’s definitely resistance to the barrier, it’s only coming from a small, though admittedly vocal, minority of Santa Barbara residents.

One of those citizens, who declined to give his name, approached the group of deputies shortly thereafter and said saving someone’s life isn’t worth obstructing his view from the bridge. The Sheriff’s personnel respectfully disagreed and the man moved on. Others against a barrier, though, approached the issue more sober-mindedly last week. Santa Ynez resident Dan Hoagland said he thought the fence wouldn’t save anyone’s life, and that suicidal individuals will simply figure out other means to kill themselves.

This argument — that a barrier wouldn’t decrease suicide rates overall, but would just push men and women toward other fatal strategies — was resolutely refuted by Dr. Lisa Firestone. Firestone, who works closely with the Glendon Association, said “access to the means” does matter, elaborating that multiple studies conducted across the country in recent years show that barriers are effective in deterring suicides overall and giving those thinking about jumping time to reconsider and seek help. All 29 people who leaped off the Golden Gate Bridge and survived, she said, reported that they immediately regretted jumping as soon as they left the ledge. None went on to kill themselves. Suicide by jumping is oftentimes a spontaneous, impulsive act, and erecting a barrier would eliminate that immediate option for troubled people, said Firestone.

Karen Aydelott, whose 41-year-old son Matthew fell to his death in September 2008, thinks a barrier would have given him enough pause to rethink his options. She tabled with other Glendon Association representatives in support of the fencing. “There’s another 32 miles of gorgeousness along the route,” she said, in reference to complaints of lost vistas from the bridge. “We’re risking lives for a 10-second view — what does that say about us?”

Son of former county supervisor Brooks Firestone and former Bachelor contestant Andrew Firestone (no relation to Dr. Lisa Firestone) came to the meeting in support of the barrier. He recounted seeing firsthand a man leap over the bridge’s short railing in October 2009 and plummet downward. Firestone explained he was driving from Santa Ynez to Santa Barbara when, on the bridge, he saw a car coming the other direction slow down and stop. “I knew in my gut the person was going to jump,” he remembered. Firestone stopped his car to get out and stop what he knew was about to happen, but couldn’t reach the man in time. “The guy took four steps forward, glanced back at me, and jumped,” he said.

Rattled by the experience, Andrew Firestone agreed with Dr. Lisa Firestone that suicide is an impulsive action, and taking away the option of Cold Spring Bridge to commit the final act is a no-brainer. “To have such a public, romantic way to express frustration, depression, and anger is dangerous,” he said. “It chills me to the bone when driving across to know that it’s a place where people go to commit suicide. It’s not healthy.”