Good-bye to Kenya’s Kids

Reflecting on Weeks of Work in East Africa

How do you bid farewell to a place that has forever changed the way you view the world? What do you say to people who have inspired you beyond words? How do you show gratitude for a more grounded and humane perspective on life? I suppose there is no other way than to say, “I promise to return.” I would feel incredibly lucky to be welcomed back.

The experience of my last week in Western Kenya brought with it a mixture of emotions. I would miss my walking morning commute full of spiky African flora, braying donkeys hauling water from the lake, and the constant waves and welcoming smiles of the people. I was excited to keep in touch with the passionate teachers I had worked so closely with. I knew I would feel inevitably detached from a community that is so unique in their passion for progress, education, health, and love for one another. However, even with these myriad emotions, I would be lying if I said I was not looking forward to swashbuckling on a safari in the Masai Mara, and later landing in a comfortable Istanbul hotel, complete with air conditioning and a rooftop bar.

My last week in Mbita District schools was dedicated to the teachers. I spent my days leading school-specific conversations based on the positives and challenges of their current education system. At some schools, we discussed the teachers’ trepidation about inclusion due to a lack of special-education training. At other schools, teachers were eager to learn new strategies and receive fresh resources to help them to better support students with disabilities in their classes. These responses were surprisingly similar to the feedback I receive from teachers in Goleta. It was exciting to work with one school in particular on enriching their already fully inclusive school program with discussions on tolerance, parent education, community awareness, and life after secondary school for students who are deaf.

During my time at these schools, the main focus of our efforts was to help dispel the myth of the “curse” of disabilities held by many people in this region of Kenya. One way we approached this issue was to change the stigma through employing community-based education strategies. The head teachers of these schools invited community members to participate in these discussions, and promised to increase school programs that include active involvement of community leaders, school board members, parents, siblings, and teachers from neighboring schools. Every school I collaborated with during the last week had different combinations of the aforementioned stakeholders present at our discussions. This dedication and follow-through by these teachers is a healthy indicator of the potential lasting effects of our collaboration in the short time we were together.

My rapidly diminishing stretch in Mbita District was spent tackling a breadth of issues. We discussed the drought currently plaguing Kenya and its devastating effects on the already-strained country. Teachers brought up the lack of access to food and clean water, a desperate need for an assessment center, the always-present HIV/AIDS epidemic, as well as the need for books, libraries, classrooms, teachers, computers, and electricity. We successfully held two grant-writing seminars, which were attended by head teachers from 13 schools.

During my last week in Luanda, more support came to the region from Santa Barbara in the form of Engineers Without Borders from UCSB (EWB-SB). I had met with the director of the Luanda water well project, David Poerschke, prior to departing to Kenya. He explained EWB-SB was similarly partnered with Benson and the Viagenco team, and said that this was their second project in Luanda. The first EWB-SB well project was visible from my porch, and it was very evident how many locals depended on the ingenious and passionate work done by the UCSB group. I felt honored to be another delegate from the Santa Barbara area collaborating with Benson and his talented team. Benson’s influence could be felt in every aspect of daily life in this region.

One member of Benson’s team, Bernard, invited me to accompany him to witness and document the three-day-a-week food donation to the elderly, a project sponsored by Viagenco. This project was founded by Visiting Nurse and Hospice Care-Santa Barbara’s (VNHC-SB) Susan Saperstein and her mother, June. I was very excited to learn more about the program and see it in action. Bernard first took me to Mercy Support Education Center, a primary school Benson had helped found so that orphaned children could have access to a high-quality education. Shortly after our arrival at the school, a number of elderly citizens and caregivers weaved their way through the throngs of frolicking children to queue up for a helping of beans and rice. Bernard explained the program to me as I snapped photos for Viagenco and VNHC-SB, and informed me that we would be visiting the homes of two of the recipients of the program.

Bernard led me from the school, through a brush-filled, meandering dirt path that wound up at a shockingly small mud shack. I was surprised to find out that it housed a 90-year-old man named David. The shack was dark, stuffy, and could barely fit a bed with a tattered and stained mattress pad, a threadbare mosquito net, and two small, rickety wooden chairs. His first wife (of four — polygamy is legal in Kenya but is declining due to the high rates of HIV/AIDS) had the charge of feeding him. David greeted me with a feeble handshake and a warm smile. The realities of his living conditions were shocking, and made me wonder how he eats when VNHC-SB does not provide the meals.

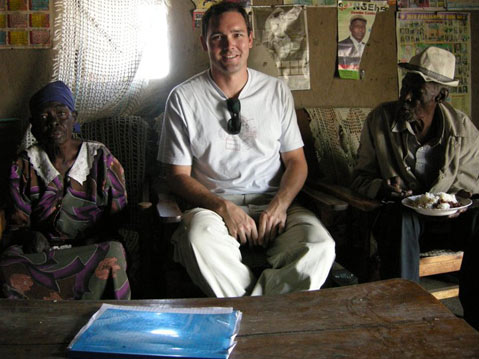

I was still reeling from my visit with David and trying to absorb the devastating level of poverty surrounding me when Bernard and I set off in search of Gilbertus and Anastasia, two more recipients of the food program. As it turned out, they lived a stone’s throw away from David, and experienced a slightly higher quality of life. By slightly, I mean that they both had their eyesight, and their house was barely larger than David’s. They were ambulatory, but Gilbertus walked hunched over in what appeared to be the late stages of arthritis. Their walls were covered in images of bygone leaders of Kenya as well as more recent political inspirations, such as President Obama. Gilbertus spoke proudly of his time as a Luandan police officer, and about how happy he was that he had a “m’zungu” visitor in his house. As Gilbertus’s spirit pleasantly permeated the room, Anastasia sat quietly and nibbled away at her meal. As we said our good-byes and took photos, I could not help but wonder how I would feel if my parents were destined to experience this type of extreme poverty in the twilight of their lives.

As my three weeks in Luanda quickly came to a close, I became aware that my experiences there were about much more than education and disability in Kenya. Though advocating for people with disabilities was my motivation for embarking on this journey, the heart of the trip became apparent in witnessing the day-to-day lives of the people I was fortunate to meet. Along the way I encountered a multitude of people with a tremendous variation of abilities, talents, and plights.

Though most of the Luanda and greater Mbita area can be described as encompassing varying degrees of poverty, I do not think I have ever met people who were so gracious and proud of the richness in their community. I witnessed firsthand the power of collective social responsibility with the goal of progress through education, health care, and clean water. I lived within the boundaries of a place where traditions are rooted in respect and love for your neighbor. I was welcomed with embracing arms, and open minds.

My goal was not to impart my Western wisdom on a culture that was distinctively Kenyan. My intention was to initiate conversations that were decided to and directed by the local people. As a result, I was given access to a way of life that has taught me countless life lessons that I will carry with me indefinitely — lessons that cannot be taught within the confines of any classroom, and lessons that have to be learned when you step outside of yourself and let go of familiarity.

In Kenya, I witnessed multiple groups of vulnerable children with disabilities living away from their families at special schools. Many are growing up without living parents, forgotten by the outside world. The people I encountered, with or without disabilities, gave me glimpses into lives that are unfortunate, powerful, and shocking. For individuals with disabilities living in the Luanda area, life at first appears bleak and insurmountable. However, the spirit of these people, coupled with the tireless efforts of Benson, the teachers, Viagenco, VNHC-SB, EWB-SB, and countless others inject hope and compassion into this at-risk region of Africa. There are many people dedicating their lives to improving the area’s quality of life and creating positive and sustainable change. Benson and everyone he is involved with are helping to provide opportunities that most of us take for granted: access to health care, healthy food and water, and the opportunity to attend school.

If you would like to learn more about any of the charitable groups mentioned in these articles, please contact the following people:

* “Donations to Orphans” or Viagenco. Contact Benson Oswago at boswago@yahoo.com

* Visiting Nurse and Hospice Care – Santa Barbara. Contact Susan Saperstein at ssaperstein@gmail.com

* Engineers Without Borders-UCSB. Contact David Poerschke at david.poerschke@gmail.com. See their website here.

If you have any questions or comments for me personally, please feel free to contact me at brent_elder05@yahoo.com

These articles are dedicated to the memory of Dr. June Downing, who recently passed away after an 18-month-long battle with cancer. June was my mentor as I was receiving my special education credential at Cal State University-Northridge, and was the one who connected me to opportunities to develop inclusive supports abroad. She was a visionary in the field and in her personal life. She will be missed by all who had the privilege to be near her.

I would like to extend a special thank you to Vanessa “S” Vance, and Katie “H. F.” Dwyer for taking the time to scour my writing and make it comprehensible to others. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Ruth Marquette and Jen Sousa for lending me their expertise on grant writing.