Things to Know with Jean-Michel Cousteau

Ocean Preservationist Talks About Chemicals in Our Waters, Fish Bones Neutralizing Lead, and His Upcoming Fundraiser at Cate School

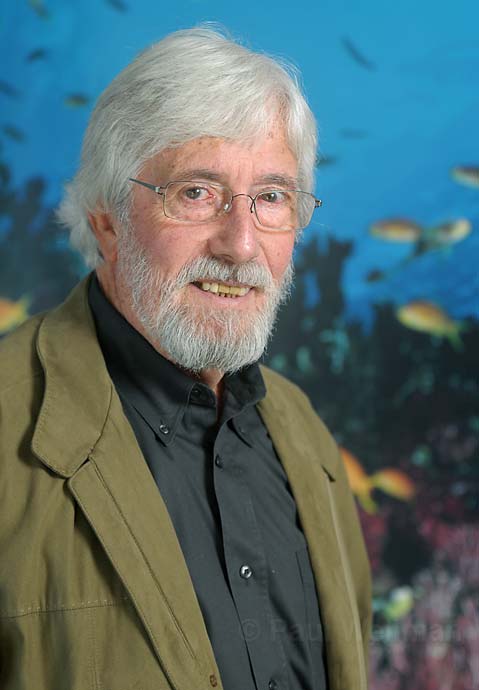

Jean-Michel Cousteau, eldest son of the late, great Jacques Cousteau, is no stranger to recognition for his ocean-related activism: He’s an Emmy Award winner, a Peabody Award recipient, and a member of the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame. In 1998, vice president Al Gore gave him the Environmental Hero Award.

As president of Santa Barbara’s Ocean Futures Society, Cousteau has made education an integral part of his preservation-minded work. So as a South Coast resident — though spending a lot of his time meeting with government officials around the world — Cousteau, along with diving partner Holly Lohuis, will speak at Cate School in Carpinteria this weekend for a fundraiser presentation and Q&A conversation.

Before the upcoming event, The Santa Barbara Independent wanted to pick his brilliant brain about teaching, Earth Day, protecting the Channel Islands, and what he sees as today’s single biggest threat to our oceans.

What can the young people in attendance expect to learn from your talk? It’s not so much what can they learn, it’s what are they going to learn. Because the amazing thing with kids is they are like sponges, and anything you make available to them — provided it’s not boring — they are unbelievably stimulated by. You can meet those kids 10, 15, 20 years from now, and they’ll remember.

I was in the state of Washington, south of Seattle, when somebody walked up to me and said, “You don’t remember me? I am so-and-so.” And I said, “No, I’m sorry I don’t.” Then the person explained, “Well, I was in your program 27 years ago. I’d like to present you my wife and kids, and I want you to know that all the decisions I make are impacted by the experience that I had 27 years ago.”

So we know we’re not wasting our time. I love to open [my talks] for questions, but I’m a little scared, because sometimes kids ask tough questions. [Laughs.] Occasionally, I have to say, “I’m sorry I don’t know the answer.”

What about the people that aren’t so young? How can you teach them? You can, but it takes more time. [With children], I think it’s mostly instinct. When a child is born, and you put him in the water, no water will go in his lungs. They have the instinct of shutting it down, because that’s what they did for nine months.

Then we scare them. We really need to rethink the way we educate young people. We need to stop using the words “no,” “don’t,” “bad.” That doesn’t help. It’s very difficult for us not to say that to young people, instead of taking the time to explain. The amazing thing is that, if you explain it, it will go in their mind right away, and they’ll never forget it.

What can people expect from the fundraiser? We’ll hopefully entertain the young people and their parents, but I would love to open it up for questions. When you talk, you don’t learn anything. By opening it up to questions, it forces you to think. It’s always my reward — I always tell people that I’m looking forward to the Q&A.

Earth Day was last weekend. What are some things that people can do to make sure that the Earth and its oceans are around for a long time to come? Earth Day is wonderful, but I wish it was Ocean Day, since oceans cover 70 percent of the planet. We all depend on the ocean. We’re all connected to the ocean. There’s only one water system. When you see the snow, that’s the ocean. When you drink a glass of water, you’re drinking the ocean. We all depend on that water system for the quality of our lives.

That means we need to be better managers of those resources which keep us alive. Whether it has to do with the use of electricity or switching to solar panels, whether it has to do with the automobiles we’re using or switching to a hybrid — everybody can do that. There are many little things that everybody can do, and at the end of the month, you’re saving money and you’re helping the environment.

The most difficult thing is to stop allowing many objects — mostly plastics — from going into the water system. We have examples where we found between eight and 12 pieces of plastic in the stomachs of dead chicks who could never fly because their parents are bringing back anything that floats on the ocean. The parent picks up that thing and regurgitates it into their babies’ mouths. That’s what we’re doing to nature and ultimately to ourselves. A plastic bag is going to kill a turtle, because a turtle will look at the plastic bag and think it’s a jellyfish.

We need to stop using the ocean as a garbage can, number one. Number two, what about what we don’t see? What about chemicals? What about when you take a tablet of aspirin. You think it’s going to take care of a headache, but where are those chemicals going? They go in the ocean.

If there is one single, biggest threat to the oceans today, what is it? I would say chemicals. They accumulate in the foundations of all life, which is plankton. So, you have planktons, which are loaded with those chemicals and metals, and these planktons are being absorbed by many animals of the food chain, all the way to the dominant species, which are the whales, dolphins, big fish, and sharks. It’s a little bit like destroying the foundation of a high-rise building.

I’ve seen toys in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. They decompose and become part of the food chain. You look at what’s happening to some killer whales on the border of Canada and the United States. There are scientists who have been studying those for 30-40 years, and now they can report to us that the mothers’ babies — if they’re able to give birth — will die within the next three years. That’s what we’re doing. What are they feeding on? They’re feeding on the same fish that we put on our plates.

And that’s when you talk about issues like PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyl], which were outlawed. They’re still there. You talk about the fire retardant PBDEs [polybrominated diphenyl ethers], which are everywhere — carpets, pillows, clothes, toys, your computer. They’re everywhere, particularly in California. Hopefully the government of California is slowly changing this. But it’s still everywhere — we breathe it all the time. All that accumulates in the food chain, and we find it in what we put on our plates. I know it sounds huge, but it starts with every one of us, and we can do a little bit at a time.

What can we do to protect the Channel Islands? First of all, we need to make sure nothing — that we can see — goes in the ocean near the Channel Islands. I know there are major campaigns to pick up anything on beaches, but we need to try to pick it up before it goes on the beach, because most of the time, if it’s on the beach, it means it went in the ocean. There are major efforts in that area, and that’s great, but we need to have better regulations. We need to communicate with our mayors, with our congress people, senators, and governor and do everything we can to improve what’s going on.

In West Oakland, which is very, very poor — about 50 percent unemployment — you have 150 families that are living on land which is loaded with lead. And where do kids play? On the ground. Where do cats and dogs play? On the ground. So we’re finding out that they have problems — attention span issues, thyroid problems, and on and on. There’s a scientist who came and asked, “How can we take care of that?” She found out that if you take the fish bones of the biggest fishing industry in Alaska (which are normally discarded) and turn them into a powder, you can inject them into the ground of those 150 families’ properties, and it neutralizes the effect of the lead. There are solutions to all of our problems.

We need to roll our sleeves up and go to work. Things are changing fast, and I believe that we can use that technology to inform people. We’re not there to blame them — we’re there to help and educate. Remember one thing: Never point a finger at somebody. That’s how you can eliminate this defense mechanism that most people have. Sit down, have a dialogue, and try to find solutions together. It works.

How do you feel about the marine protected areas? Some people say the new rules are hard to enforce. Enforcement is critical. If you have a law, but don’t have anybody to make sure you respect the law, that’s useless. We need also to understand that those protected areas have been created for good reason: It’s to make sure that those species are not going to disappear. We need to change, and we can by learning and going in the right direction. That means huge opportunities in science, in farming, in research, in communication. There’s going to be thousands and thousands of new jobs because of that.

What other projects do you have in the works? One, I want to do a show on the water cycle in 3D, with children, to present at Rio+20 [a worldwide conference on the environment] in June. Two, I want to do a one-hour special on the fish bones that I mentioned. And I’m trying to do a television series called Ocean Alive, and I want young people to be involved. I want to dive with young people and have them speak to the world from underwater. I want some dedicated personalities to be involved, either underwater or above water, to communicate with these young people or for these young people to communicate with them.

What makes a big difference is to make sure that we have new, young ambassadors who are going to be the decision-makers of tomorrow, communicate with their family, with their parents, because they’ll coil that knowledge. And there’s one thing, and I know how difficult it is presently: the difficulty of schools to get kids out of school. But we need to get them out in the environment — whether it’s in the ocean or on land — to feel, sense, smell, touch. They will learn a lot more than by being sitting in a classroom. I keep begging for that to happen.

We have a program on Catalina [Island]. Thanks to sponsors, we are able to take a classroom from downtown L.A. with kids who have never seen the ocean and bring them to Catalina. You take these boys and girls, and in three to five days, you teach them to swim, you teach them to snorkel, to go snorkeling at night with a flashlight to see the lobsters crawling on the ocean floor. When you send those kids back to downtown L.A., they are your best ambassadors. They’re going to talk to their friends, their neighbors, their parents. That will change their life.

Those are the things that we need to do a lot more. It’s an exciting time, but time is of the essence. If you protect the ocean, you protect yourself.

411

Jean-Michel Cousteau will be speak at the Cate School Theater in Carpinteria on April 29 at 6 p.m. For tickets and more info, visit cfsfamily.com. Proceeds will benefit Carpinteria Family School Green Initiatives.

For more information about Ocean Futures Society, visit oceanfutures.org.