Arts & Lectures Kicks Off Sci-Fi Fridays

Robots! Aliens! Body Snatchers! Invade the Courthouse

Remember the future? It used to come in two cool flavors back in the day: There’s the bright, Mechanix Illustrated-meets-The Jetsons brand, promising technology that trumped drudgery forever. (Think streamlined robot assistants and houses that float underneath climate-conditioned domes.) But there is another, darker future that paradoxically never ages, no matter how many times we watch it on video or late-night TV. Let’s call it “Tomorrow Noir,” the fantastic movie-threat version of the future in which Earth gets overrun by the unexpected — usually due to our own shortsightedness. In this realm, aliens come to induct us into their passionless super-efficiency schemes because we messed with atomic power. (They don’t like it because we pose a threat to their intergalactic order.) In the other Tomorrow Noir mode, we’re hoisted with our own petard by way of atomic dabbling, which backfires on us and permanently changes the normal scale of things. (Think gigantic ants or crabs, or shrinking humans, or even, from time to time, an unleashing of our own latent powers.)

Luckily for us, Tomorrow Noir is infiltrating our near future thanks to UCSB Arts & Lectures and the Santa Barbara Parks Department. Starting this Friday, they’ll expose us to nearly every kind of Apocalyptic It (or Apocalypse Then) by way of their semiweekly free movie screenings at UCSB’s Campbell Hall (Wednesdays) and the S.B. Courthouse Sunken Gardens (Fridays). Why? Because they know we love to look ahead and find some mayhem, like ginormous flying saucers hovering over the White House. These kinds of images give viewers the sublime rush Susan Sontag calls a “cinematic charm,” made from our own guaranteed inadequate responses to the “unassimilable terrors” (atomic or otherwise) introduced by the modern world. In fact, this charm is immediately observable in the series’ thought-provoking and awe-inspiring opening film, The Day the Earth Stood Still. Directed by Robert (The Sound of Music) Wise, the film features Sam Jaffe as the requisite Einstein-like scientist, as well as Gort, the giant, technology-nullifying robot with the unforgettable mantra: “Klaatu, barada, nikto.” The smartest of the 1950s classics, The Day the Earth Stood Still casts humanity as both godly and venal. It also introduces the disintegrating ray, which later became a genre staple and a reminder of obliteration, which, also according to Sontag, is what we really mean when we talk about flying saucers.

From D.C. we travel way north to discover truly savage aliens, the backbone of the Tomorrow Noir genre. There we meet The Thing from Another World (usually just called The Thing), a movie secretly codirected by the great Howard Hawks and set in an arctic military outpost just to ramp up the paranoia factor. Kindly note the vague pronouns that run through these movie titles, like the following week’s film, It Came from Outer Space. It’s one of the few true B movies in the series, and it comes from the pen of the recently deceased Ray Bradbury, who wanted to create an alternative myth: invaders who want to bring us peace. (Of course, we decide to blow them up anyway.)

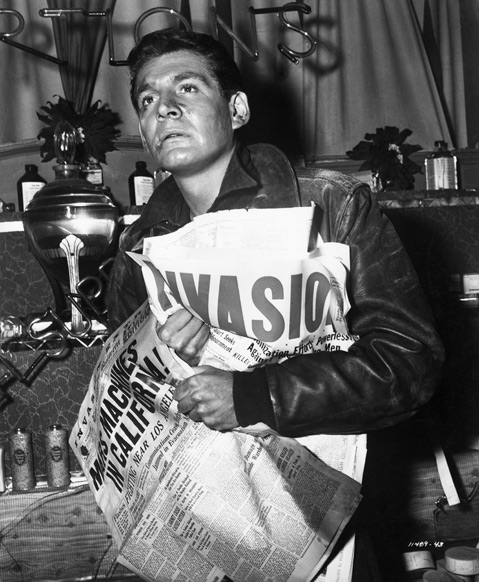

Invasion paranoia is a key theme in Tomorrow Noir, and the next three films propose to overwhelm us with it. The War of the Worlds, with its classic blending of a novel by H.G. Wells and Orson Welles’ famous 1938 radio hoax. This film introduces the first-ever hunky scientist — Dr. Clayton Forrester, played by suave Gene Barry — and features the cleverest of alien-disposing devices. Then comes Them! — in which giant ants attack Los Angeles against the backdrop of a compelling desert tale. (Keep an eye out for a cameo by our favorite developer, Fess Parker.) Next up is the classic paranoid thriller Invasion of the Body Snatchers. This is the one most oldsters consider a parable about either spreading communism or conformity. Either way, the pod people alight upon a major literary theme found in the works of Salinger and Pynchon: the wholesale downscale of humanism.

But Arts & Lectures’ brilliant film programmer Roman Baratiak saved the best for last. First, there’s the great Forbidden Planet, a space-opera rewrite of Shakespeare’s The Tempest with special effects by Walt Disney. Forbidden Planet also features Leslie Nielsen and Anne Francis alongside a robot who teaches us that we don’t really want to transcend our own passions and bodies and that a pure life might be where alienation begins. But leave it to that great testament of 1950s future fears to sum up the series: The Incredible Shrinking Man. The film ends as its protagonist realizes that a radioactive cloud was bringing him simultaneously down and face-to-face with the junction between the infinite and the microscopic realms. “I was continuing to shrink to become, what? The infinitesimal?” says our hero. “What was I? Still a human being? Or was I the man of the future?” he asks, staring toward the stars.

Now, some 50 years later, we know these prophecies were wrong. Aliens and mutation-ridden nightmares never claimed our present, but they still thrill us, and in an age when growing technologies have altered our climate — possibly forever. Chances are some of this summer’s moviegoers might even hope that awesome aliens do come down, if only just to remind us to be human again.

4•1•1

For a full schedule of summer screenings, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu.