Judge Eskin’s Last Hurrah

Veterans Court Holds First Graduation

Although Judge George Eskin officially hung up his black robes nearly a month ago, last Friday’s event — the first graduation of Santa Barbara’s budding veterans court program — may have been the proudest moment of his 10-year tenure on the criminal bench. Looking at the ceremony strictly by the numbers, it was an exceedingly modest affair. Five men who’d served in the armed services and subsequently got themselves in trouble had managed to stay clean and sober, attend therapy, and stare their demons in the eye for about a year each.

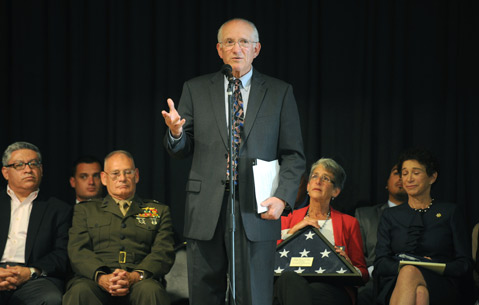

For so doing, the criminal charges against them were either dropped outright or reduced. The four graduates — one could not attend — stood at the front of the main hall at the Veterans Memorial Building along Cabrillo Boulevard. Celebrating with them — and bearing witness to their success — was not just Judge Eskin, who got the veterans diversion court off the ground, but a veritable who’s who of Santa Barbara’s political class. There was Eskin’s wife, State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, District Attorney Joyce Dudley, Judge Jean Dandona, three county supervisors, three Santa Barbara city councilmembers, Goleta’s mayor, the Public Defender, representatives from a host of other elected officials’ offices, and a handful of city cops, many in white gloves and their dress blues, bursting with pomp and solemnity. The rhetoric of the event, as one speaker put it, was all about “compassion not condemnation, rehabilitation not retribution.” As group hugs go, it doesn’t get more high-octane than this.

Veterans courts, like drug courts and other diversion programs, are not particularly new or even novel. There are at least 200 throughout the country, including one in Santa Maria that is about two and a half years old. What distinguishes veterans courts from other diversion programs is that there are actually resources — money and programs — available to help returning servicemen and women struggling with mental health and substance-abuse issues. The threat of criminal prosecution is brought to bear to induce vets to avail themselves of the help they might not otherwise seek. But even so, Santa Barbara’s court personnel — facing sustained budget woes — have been hard-pressed to take on unwieldy new programs requiring the active collaboration between a wide array of agencies with conflicting missions in the face of chronic shortfalls.

Getting all these parties — prosecutors, defense attorneys, probation officers, mental-health caseworkers, law enforcement, and the Veterans Administration — on the same page was Judge Eskin. He never served, having blown his knee out in high school playing football. But his father served as a lieutenant colonel in the Army during World War II and was stationed in Europe. His uncle was part of the D-Day invasion of Omaha Beach. “This is my way of trying to pay back,” Eskin said. It took a lot of stubbornness on his part to do so, recalled prosecuting attorney Michael Carrozzo. “I can’t tell you how many times I heard him told, ‘No, it can’t be done,’” said Carrozzo, who served as the District Attorney’s point person in the program. “And he’d say, ‘We’re going to do it anyway.’” It was Eskin who interviewed judges who presided over successful veterans courts elsewhere in the country. It was Eskin who brought in experts in the special care required by combat vets. And it was Eskin who shoehorned Carrozzo — who served four years as a judge advocate general as an Army captain at Ft. Irwin — to get involved.

Eskin is quick to heap praise on Carrozzo for making the program work. Carrozzo functions as the point person and gatekeeper who weeds out vets who got into trouble well before their years of service from those whose service contributed to their problems with the law. “I never deployed, but I know what some of the consequences of deployment are,” Carrozzo said.

Carrozzo said he’s screened 70 veterans for the South Coast Veterans Court thus far; aside from the five who graduated, 32 are still in programs and treatment. Some wash out, he said, others decline participation, reasoning that they’d serve less time in Santa Barbara’s overcrowded jail than they would in treatment. The typical offender is looking at county jail time, not state prison. No sex offenders are considered, nor are individuals charged with violent crime. The more serious the offense, Carrozzo explained, the more weight he places on the individual’s service record.

For Eskin, the lightbulb moment came in 2006 when presiding over the case of Gulf War vet Steven Lopez, who pled guilty to carjacking after having a psychotic break while confronting his boss, who’d just fired him. When police tracked Lopez to his residence in Isla Vista, they claimed he resisted arrest. Lopez said he was on his knees with his arms in the air trying to surrender. But when one of the officers executed “a flying knee” to his back, Lopez said, “It was on. We fought. It was bad.” Combat vets, he cautioned, don’t respond “normally” to displays of police authority. “It’s fight or flight,” he said. “In my case it was both.”

There was no veterans court at the time. But Eskin was struck that Lopez, then 33, had no criminal history, not even a misdemeanor. His high school record was so exemplary he’d been offered a “full ride” scholarship to UCLA. But Lopez chose the military. He’d served in high school ROTC and, as a child of immigrant parents, said he wanted to do his patriotic duty. And being a young dude, Lopez acknowledged, he was looking for action.

He found it. And then some. Eskin would later say of Lopez’s wartime experience, “Something happened.” Of the 250,000 troops who served during the Gulf War, Lopez says only one percent saw actual combat. “I saw it every day for about a year,” he said. When Lopez was discharged one year later at age 19, he was deemed 30 percent disabled. “I was involved in some shit,” he said in a recent interview. “I was messed up.” Friends would wonder what happened. “How about two decades of night terrors,” he answered. Lopez said he sought help from the VA half a dozen times but was never told there were programs available. For 15 years, he held it together, sort of, drinking too much, getting high, and not getting along. Then he got fired from his job and everything exploded.

“I was looking at five years in state prison,” Lopez said of his first offense. Over the objections of the prosecuting attorney, Eskin said he sentenced Lopez to five years felony probation on the condition he obtain mental health treatment. Based on the calculus of California’s three-strikes law, Lopez got his first strike.

Four years and six months later, something else happened. Lopez and his girlfriend at the time got into an argument. She picked up the phone to call the cops. Lopez picked up a piece of wood and said, “If you call the cops, there’s going to be trouble.” Lopez insists he was talking about the violence that might ensue between him and the police. Prosecutors didn’t see it that way. Even so, he got a second chance based on his military history. More probation, not prison time. But he also got a second strike added to his record. If he screwed up again, Lopez was now looking at 25 years to life. “That’s a hell of a pill to swallow,” he said.

Then in 2011, Lopez got in a fight with his brother. He claims his brother punched him first and that he didn’t want to fight. So he pulled a knife as a defensive maneuver. And he also smashed the windshield of his brother’s car.

By the time Lopez’s case made its way to Judge Eskin, the veterans court had been established. Eskin — when first announcing the formation of the new specialty court — had cited Lopez’s case in particular as one of his inspirations. Now, Lopez was actually before him. But Carrozzo had second thoughts. As far as violent offenses, Lopez’s actions were on the “upper end,” Carrozzo said. “He was a risk.”

At Eskin’s insistence, Lopez was invited to participate. He was sent to a treatment facility in L.A.’s Koreatown — Bimini Recovery Home — known for its boot-camp, no-second-chances discipline. There he stayed one year. Treatment there wasn’t cheap — $1,500 a month — but the feds picked up the tab. “I was finally forced to face the things I didn’t want to face before,” Lopez said. “Mental illness is so taboo,” he said. “If you don’t talk about it, it comes out,” he cautioned, “but it doesn’t ‘come out.’ It explodes.”

What made the difference for Lopez was that he went through the program with other combat vets. “When I got out in 1992, I was the only one. I was really lonely. Now guys like me are a dime a dozen, and I’m not alone anymore,” he said.

Indeed not. During Friday’s graduation, Fred Lopez, a retired brigadier general with the Marine Corps, reminded those in attendance that an estimated 20 percent of the 2.3 million men and women who served in Afghanistan and Iraq suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Many will wind up homeless; some will become enmeshed in the criminal justice system. Of the veterans court, Fred Lopez said, “This is a great start, but we need to do more,” adding, “They fought for us. Now it’s our turn to fight for them.”

Since his most recent run-in with the law, military authorities have reclassified Steve Lopez 100 percent disabled, or as he puts it, “100 percent retired.” Lopez is currently studying to become a counselor for vets struggling with addictions. Looking back, he recalls his first meeting with Judge Eskin. “I was saying they’d be seeing a lot more people like me,” he said. “I told them they’d better get ready.”

Below is an interview with Judge Eskin about his time on the bench, treating and sentencing addicts, and the need for sentencing reform:

So why retire? I was one of the oldest attorneys appointed to Superior Court when my appointment was made — 65. If I were to remain on the bench through the second term I would be 80. There were two precipitous events. First was [Judge] Ed Bullard’s sudden death. He was only 59. The second was my daughter Jenny giving birth to my new granddaughter. According to the actuarial tables, I have 12 years left. So how do I want to spend those remaining years?

And there were influences that made the job much different from what I perceived when I was appointed. The budget constraints have made the job much more difficult. You can’t do this, you cant do that, there isn’t the personnel, there aren’t the programs you can refer people to, there are mistakes made, files slip between the cracks. People are doing far more with far fewer resources.

How does that affect you and the cases you handle? What does ‘handle’ mean? We don’t have that many trials. On the criminal side, why does the DA have a 90 percent conviction record? Why does every DA across the state have a 90 percent conviction record? Because 90 percent of the people plead guilty to something. Maybe 5 percent of all cases go to trial. The others are dismissed or diverted. So what does ‘handle’ mean? It’s trying to figure out what to do with the 90 percent of the people who plead guilty and the others who are convicted to increase the likelihood they won’t re-offend. And there are fewer options available to a judge now. The budget cuts have eliminated alternatives to incarceration. So that’s a big frustration.

The burden on the public at large is there’s less access to the courts for them. It’s just not a very healthy environment. It’s amazing the court personnel are available to work as well as they do with reduced morale.

You’ve been concerned about court security over the years. How has that changed? We recently had some additions to the Figueroa Building that increased the level of security for ingress and egress. The security situation in the historic courthouse is somewhat appalling from the judges’ perspective. None of us are able to get from chambers to our cars without passing through crowded hallways with the relatives and friends and associates of people we’ve just sentenced or who have come before us in a variety of hostile situations.

Has anything happened because of this? We’ve been fortunate that hasn’t happened and I hesitate to say yet. There have been threats but nothing that’s been a major catastrophe like someone getting shot or stabbed. But I can’t get from my car to my courtroom without passing through crowded hallways. It’s a tragedy waiting to happen. From my narrow perspective, that’s a big deal.

You started the veterans court about a year ago. How is that going? It’s going very well. The thing I’m most proud of is we did this without any grants. We made it work as a result of everybody pitching in and making it happen. We haven’t had any administrators. Most important in my opinion is Deputy District Attorney Michael Corozzo.

How so? He makes the difference because he is a military vet himself, a JAG officer, a little older, more mature. He exercises good judgment and assigns a high priority to the quality of a vet’s service. He is understanding of the sacrifices that were made and the significance of the injuries that were incurred. He tries to find a way to get a military vet into an appropriate treatment program.

Is there a typical profile of a vets court defendant? Nearly all the people have some kind of drug and alcohol problem. Many have mental health issues and histories. Many are homeless. One who will be recognized Friday appeared before me years ago. He had earned an academic scholarship to UCLA out of Oxnard High School; it was a full ride. He’d done extremely well. He decided instead to serve his country by enlisting and going to the Gulf War. Something happened. I don’t know what, but something. He returned home. He was clearly damaged. He came before me 6 or 7 years ago. He was working as an auto mechanic and he was fired from his job and he showed up at his place of employment with a big stick and he was doing Aztec Indian chants and causing quite a scene at the dealership.

He went into the former supervisor’s office, confronted him about being terminated, there was a mild scuffle. He ran out. He was on a bicycle. He rode to another dealership where he saw a vehicle parked in a lot with keys in the ignition and took the car. And he drove away to his residence in Isla Vista. He was charged with a variety of offenses. It became clear he needed mental health treatment which we were able to provide at the time, over the objection of the deputy assistant attorney at the time. In any event, he cleaned up his act, got a job at a local repair shop, and was doing very well for a while. Then something happened. I don’t know what, and he re-offended and was back in the system. Only this time we had the veterans treatment court. And he’s been at the VA hospital doing extremely well by all reports. He’s going to graduate.

We’ve been very fortunate because the county has a veterans service officer named Andrew Miller. Vets come in and say they’re not eligible for services. He plugs their name into his whatever it is and finds out that they are. Or how to get past the red tape that says they’re not. He’s just fabulous.

What about the other people with drug, alcohol, or mental health problems in jail who aren’t veterans and can’t get services from the VA? We have to have a major paradigm shift. It includes how we deal with mental illness and its effects on anti-social conduct. And we have to have the courage to do something drastically different about the abuse of drugs and narcotics. In my opinion, state prison is a place we send people who commit violent crimes. Violence is not limited to physical violence. It includes financial violence. People who exploit elders exploit their positions of trust and confidence and steal, they commit acts of violence that have serious consequences. But the state prisons should not be a repository for people with mental illness or addictions.

So you’re saying drugs should be de-criminalized? Yes.

What do we do instead? What works? The most discouraging news about methamphetamine addicts is that treatment doesn’t work. But in terms of societal values we should look to some other countries who have dealt with this in more humane and effective ways. I think the European and Scandinavian countries have approaches to drug use and abuse that do not include state prison or incarceration. Education and mental health treatment is so far superior to the expense associated with court proceedings and incarceration. You just have to get people to accept a different way of approaching it. Drug addicts, no matter what the drug, should be treated for their addiction. People who sell drugs for something other than supporting their addiction should be treated more harshly. Maybe they need incarceration.

I always hear how from law enforcement officials that we don’t put people behind bars for simple possession. How many people did you see in your court? A significant portion. I wish I could give you a number. A significant portion of our cases are DUI. How many are public intoxication? And how many are now called burglary for what used to be called shoplifting. This is one of the flaws in our system. If I enter a store with the intent to steal a tube of toothpaste, I’ve committed a second degree commercial burglary. And if I’m convicted of that crime I now have a prior theft conviction which can be used to enhance my next shoplifting offense and make me eligible for prison. So not only do we need prison reform but we need sentencing reform. Drastic prison reform and drastic sentencing reform. Every day of the year people are received at the Department of Corrections as a result of my order sentencing them there. Every day people are released on parole. How many people? I don’t know. I can’t help but believe we could manage the spigots and reduce the population without endangering public safety.

How is that going? The governor vetoed a bill this session that would have been of great assistance. It would have given the DA and judges the discretion to reduce simple possession of narcotics from felony status to misdemeanor status. It would have given judges discretion to avoid state prison sentences that are now required. You reduce the flow into the bucket by having other options to incarceration.