McLuhan’s Message

Understanding Media at 50

There should have been conferences and lectures, seminars and symposiums. Discussion and debate should have reverberated through print and television; the Internet should have been frantic with countless hits and posts and blogs. Instead, there appears to be nothing, or next to nothing. It is the strange and fateful anticlimax to one of the most unique intellectual moments—and noteworthy publishing events—of the 20th century.

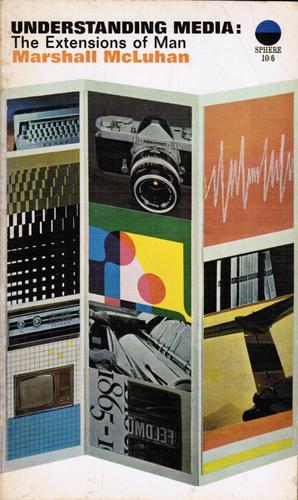

In 1964, a largely unknown Canadian English professor published his most important book, Understanding Media. A small volume with an inconspicuous title, it was the great loblolly masterpiece of all the author’s conflated ideas. Frequently trenchant and hortatory, often contradictory and confused, it was an astonishing success, and we have been using some of the author’s language, living with his ideas or avoiding them, ever since. McLuhan seemed to be telling us something original and important about the time in which we were living and the new age that was nearly upon us.

The book was a huge bestseller and the author, a gray-haired gentleman, angular, tweedy, and slow to speak, became a colossal media celebrity. He was called a “pop philosopher,” equated with an artist like Andy Warhol. He was the “television guru,” and in an era of competing sensation and controversy, he was a polemical lightning rod as incendiary as myriad political radicals, a drug and counter-culture advocate like Timothy Leary, or countless British and American rock bands. He was the advocate, prophet, and expounder of the virtues of television and electronic technology, and he estimated or adumbrated even more than he could have foreseen.

McLuhan had a small scholarly reputation based on his first two books. In The Mechanical Bride, A Folklore of Industrial Man, (1951) he presented in what he liked to call a “mosaic format” a kind of scrapbook of images and commentary on contemporary American culture. Comic books, advertising, movie posters, the book is part sociology and part broad satire. McLuhan would later be characterized as an indiscriminate champion of the bric-a-brac of popular culture, which he was not. What fascinated him was the style of communication in mass culture, the use of art and photography, clichés, slogans, jingles, and the powerful efficacy of all these techniques as “packaged understandings.”

The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) appeared when the author was about fifty years old. Here the foundation is laid for a few of his basic ideas. The most important is the historical creation of “typographic man.” As a historian McLuhan roughly falls within the group that believes that tools or advances in technology (the wheel, the plow, the pulley, etc.) become absolute determinants of change, growth, or style of civilizations. This type of reasoning is sometimes referred to as “flattening out history,” because such a single-minded idea will always have the same result: All the irregularities and difficulties are removed. A simple formula is presented as the key to everything. In McLuhan’s case the most important factor in all civilization is communication and modes of communication. It is around this social nexus that virtually everything else is determined. In McLuhan, alphabetical civilization has dominated in the West since about the time of the ancient Greeks. But with Johannes Gutenberg and the creation of movable type and the printing press around 1440, everything was compounded and magnified. A media creates its own social environment; civilization is changed and people are changed.

It was common in the ’60s to see McLuhan as sui generis, entirely unique and unexpected in his ideas. He was not. In general, McLuhan was a kind of literary modernist, most devoted to James Joyce, especially the oral and meta-literate novel Finnegans Wake. But this kind of modernism also allowed for a reactionary side, and McLuhan was conservative in an Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot kind of way. He was also a convert to Roman Catholicism, like one of his other heroes, G. K. Chesterton. He looked back as much as forward and was interested in those leveraged historical occasions when a fundamental change of axis takes place. The change in human society from oral to alphabetical and print culture, which interested McLuhan, was an area that the American scholar Milman Parry had explored. McLuhan’s peers and colleagues Walter Ong and Eric Havelock became scholars in this area, and it remains a subject of interest in scholarly and academic circles.

For McLuhan, however, the biggest influence came from his friend, the Canadian academic Harold Innis. A professor of political economy at the University of Toronto where McLuhan also had a long career, Innis was a theorist of social history and communication. It was his original idea that types of media have a bias, or their own sort of meaning or defining power. When McLuhan published Understanding Media the first chapter was “The Medium Is the Message.” This key concept, expanding on Innis, means that styles of communication carry with them ideology and social organization. The medium molds the way people think and act in the world. The organization of the senses, both relations in time and space, are created in human beings by the type of media that is most pervasive or dominant. The medium is the paramount message, more important than any content that may be communicated.

For McLuhan, the rise of “typographic man” and print culture carried with it nearly every social and personal ill imaginable. Oral, preliterate culture had been harmonious and coherent and relatively peaceful. With the alphabet came the Roman Empire. The Gutenberg calamity was the deathblow to a more organic or multilevel personality and gave rise to strident nationalism, destruction of shared values, modern alienation, modern individualism, modern conformity, passivity, and violence. Print culture is linear, tenacious, and driven, and so limiting of human consciousness that MuLuhan suggests at one point it may have created schizophrenia.

But there is hope. Electronic media, especially television, returns humanity to the lost Eden of oral culture. It is more suitable to the senses, audile and tactile. It facilitates again the community and tribal aspect of human civilization and helps create the “global village.” Electronic technology will repair the rift in human consciousness created by movable type.

McLuhan’s theories have a prodigious inclusiveness and are a virtual sensory and cognitive description of the human condition. It is very speculative neuroscience, and it goes further. Different media have very specific effects on the senses and can be designated as either “hot” or “cool,” depending on impact or type of interaction. The assignment of “hot” and “cool” status always appears arbitrary and paradoxical. Print is hot, television is cool, radio is hot, speech is cool, and so on, with little real explanation of what this means. Also, while electronic technology has advantages, a medium like radio can be narrow and deceiving. When McLuhan insists that the political triumph of Adolph Hitler was attributable to the nature of radio technology and could never have happened in a television culture, more than one reader felt they had reached the summit of intellectual tomfoolery.

McLuhan’s success, keep in mind, was a literary success. The prose of Understanding Media is vehement, propulsive, and thrilling. There is always something partial, fragmentary, and inspired in the writing; the reader is always waiting for what happens next. His prodigious erudition is flung about on every page with infinite reference to other writers and a profusion of quotations. He is sometimes farsighted and sometimes farfetched. In McLuhan there is statement, then overstatement. There is a supportable fact followed by some unsupportable extrapolation and conclusion.

McLuhan’s new ideas and his own hot style brought him enormous attention and many readers. It also brought him a lot of critics. This was the era when Dwight MacDonald decried the ignoramus “mass-cult” of American culture, when Herbert Marcuse described the “one-dimensional man” of commercial society. Anyone praising television in any form was at best wrongheaded or more likely a fraud. And when McLuhan wrote that the best part of any newspaper or magazine was the advertisements, he established himself as a buffoon.

A few individuals, like the journalist Tom Wolfe, sounded hosannas and said McLuhan was possibly the most important thinker since Newton and Freud. Few others were as enthusiastic. In fact most critics (social and historical types) had a delightful time flaying and roasting McLuhan. His reasoning was wrong, his history was wrong, his chronology was unbelievably wrong, and his assumptions and leaps of imagination were madness. The literary critics hated him and the Marxists loathed him. George Steiner, Harold Rosenberg, Susan Sontag, Dwight MacDonald, every critic and public intellectual seemed to have something to say about McLuhan. There was so much commentary that anthologies of critical essays were published within a few years after Understanding Media appeared.

There was always an underlying assumption that McLuhan belonged to the youth of the period. Indeed young people of that time were the first generation to have come of age with television as part of their lives, but their chief virtue was that they could actually read McLuhan and follow all his references from Shakespeare to Cicero, James Joyce, and Alexis de Tocqueville. The American generation of the 1960s was probably the most literate generation in the history of the world. They are still the largest group of book buyers in the United States. They read McLuhan because he was part of the new ideas and climate of the times. And of course, as time has gone by, it seems that the generation that McLuhan really predicted or anticipated have barely ever heard of him, and certainly never read him.

Marshall McLuhan was not the first prophet to be off by a generation or two with his predictions. He was not the first to say something would come about without knowing very well, or completely, how it would happen. Computers are mentioned only in passing and infrequently in his work, but at his most oracular he wrote, “The computer promises by technology a Pentecostal condition of universal understanding and unity.”

The universality of computers is a condition that daily is being achieved; the consequences of this are more problematic. The “global village” may have become a tangible reality, but a skeptical view of this is more realistic than Pollyanna expectation. McLuhan died in 1980 before the computer revolution had really commenced. He was forgotten in popular culture but continued to be valued in scholarly circles as a theorist and one of the creators of communications and media studies in academia. Some media scholars, nevertheless, like Todd Gitlin, have almost been eager to forget him, to dismiss him as a crank.

McLuhan had a lot of ideas and subsets of ideas. But he had one very big idea: that human civilization had passed through two stages of communication history, oral and print, and was embarking on another: electronic media. He believed the new media would change the way people relate to themselves and others and would change societies dramatically. Is the computer, then, the ubiquitous laptop and other devices, the McLuhan “audile-tactile” dream come true? There is no way to know. And it will take at least another 50 years to make a full evaluation of the work of Marshall McLuhan.

Meanwhile, the Gingko Press in Berkeley has kept all of McLuhan’s work in print. Very artful and handsome editions, his books are available for all the consideration and debate they continue to deserve.