Wade Graham on Living the Dream

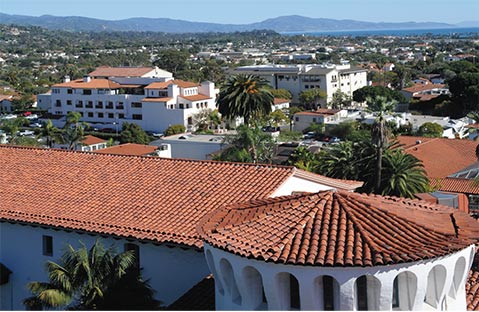

Author Ponders Whether Santa Barbara Is the Original Dream City

What do San Diego’s Balboa Park and the Montecito Country Club have in common? If you answered that they are both quite pleasant environments, you are certainly correct, but if you said architect Bertram Goodhue, give yourself a rousing Spanish Colonial “olé.” In his new book Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas that Shape the World, historian and landscape architect Wade Graham makes the case that the extraordinary beauty of Santa Barbara’s carefully tended architectural identity began not in Spain or Italy, but rather in the imagination of Bertram Goodhue. Graham cites as evidence for this claim the detailed traveler’s reports that Goodhue created between 1896-1899 of “three romantic, out-of-the-way, overlooked sites that still boasted ancient examples of buildings and bygone patterns of life.” Goodhue rendered each of these locations — Traumburg, a medieval town in German Bohemia; Villa Fosca, a Renaissance villa with elaborate gardens situated on a remote island in the Adriatic; and Monte Ventoso, a hillside village in northern Italy with a church and a piazza — in exquisite ink drawings that showed not only the relation of the landscape to the architecture but also detailed architectural plans of the major buildings and carefully observed sketches of daily life. To these elaborate drawings Goodhue appended “lively notes” recalling visits and conversations with the people who lived in these towns.

What’s the catch? At the time, Goodhue had never been to Europe, and all three of these portfolios described not real places but fantasies, or “traumburgs,” dream cities conjured out of the young architect’s budding imagination. This, according to Graham, is the origin of our famed paradise of a built environment, the idea of a “new kind of place: one with the economic and social advantages of a city, but none of its disadvantages.” The book’s opening chapter goes on to describe El Fureidis, the fabulous estate in Montecito that Goodhue created for his patron, James Waldron Gillespie, as the prototype of the contemporary suburban “castle,” an independent single-family dwelling designed to connect one’s current socioeconomic status with an artificial and imaginary version of the distant past. Subsequent chapters look at a range of equally influential notions about what the city could or should be, from the neoclassical “monuments” that establish cities as seats of governmental power to the tall “slabs” characteristic of both financial centers and public housing. Each designation comes complete with an origin story detailing the career of a particularly significant avatar of the style: Frank Lloyd Wright and the “homestead,” urbanist Jane Jacobs and “corals,” which are mixed-use, code-controlled groups of buildings that share a limited range of historicist styles.

As urbanists go, Graham is definitely a contrarian. For every predictable hero, like Jane Jacobs, there’s a surprise, such as his admiring portrait of Jon Jerde, the man who created Universal CityWalk, Horton Plaza in San Diego, and the Fremont Street Experience in downtown Las Vegas. When I spoke with Graham recently by phone, he emphasized the fact that in his version, urban design “is all the same story — the real world has always been constructed by engineers of our desire, and we have always lived in the run-down detritus of their fantasies.” Even today’s obsession with green projects and sustainability looks like self-deception to Graham, who compares LEED structures to space stations, as they make “the same promise of disconnection from the negative environmental impact of human habitation.” “The intelligentsia leans toward the future” he told me, “and green cities are just the latest version of greenwashing our dependence on natural resources. As a society, we have a magical belief in the power of objects, and science is an extension of that cargo cult mentality.”

Asked about the immediate future of Santa Barbara, where he was born and grew up as a UCSB faculty brat, Graham waxes more optimistic, stating that, despite the threat of significant population increases, we are still better off than most, even those who reside in the supposed models for the American Riviera. “In many ways, Santa Barbara is better than Andalusia or Florence,” Graham said, adding that he has not written Dream Cities to denigrate the work of architects and urban planners, but rather to educate non-architects in the various concepts that drive the world’s most common urban-planning conventions. Although it is not one of the forms addressed in the book, Graham cites the “ranch burger” as the most typical residential concept in Southern California. “A ranch burger is a satisfying but off-the-shelf, one-story, single-family home with a front and backyard and a covered garage or carport,” Graham explains. Asked if the ranch burger is “sustainable,” Graham observes that, “there are already too many of them, especially in greater Los Angeles and in Orange County, because here in California, everyone wants to live like a hidalgo.” What are the consequences of the ranch burger explosion? “Crazy long commutes, bad traffic, you name it.” And the alternatives? “Skyscrapers in Westwood and apartment block towers in Santa Monica, and this is already developing into open conflict on the Westside of L.A. People in Hollywood don’t want to look at a skyscraper out of their living room window.” Asked if there could be a middle way between the Manhattanization of Los Angeles and a zero-growth policy, Graham said that he thinks there has to be a middle ground because “it’s the all or nothing dreams that are the sources of the biggest and most destructive failures.” In an attempt to end things on a bright note, I turned the conversation back to Santa Barbara by asking Graham, who lives in Echo Park, a hypothetical question. “Okay, imagine you’ve got a couple of million to spend, and you are going to buy in Santa Barbara. What is it going to be?” Without hesitating, he said “something on the west side of downtown, maybe on Bath Street, and with a courtyard. That’s the way we should be living here. Those courtyard bungalows are the real indigenous architecture of Central Coast beach towns.”