Joel Alcox Is Resurrected

Did This God-Loving Man Serve 25 Years in Prison for a Murder He Didn’t Commit?

Somehow, 25 years of prison hasn’t hardened Joel Alcox. At age 52, he has the same gentle handshake and easy chuckle as he did when he was convicted of murder as a young Lompoc rocker. Apologizing as he slipped on reading glasses to text his new wife, he’s still unfailingly polite. Only his thick prison yard muscles under a Mickey Mouse T-shirt betray where he’s been.

In mid-May, Alcox and I sat at a Starbucks near his home in San Bernardino. He’d just finished another long day of delivering tires. He rubbed his cramping legs. The sun was setting, it was cold, but he chose a table on the front patio to sip coffee. He liked being outside and sitting where he pleased after decades under lock and key. “It’s the little things,” Alcox said.

A week earlier, on May 11, in the same courtroom where he was convicted, a Santa Maria judge overturned his sentence of 25 years to life for the 1986 shooting death of a Lompoc motel owner. The stunning ruling in an otherwise long-forgotten case marked a major victory in the tireless fight to prove Alcox’s innocence, and it cast a dark shadow of doubt over the police and prosecutors who’ve been accused of putting the wrong man behind bars. Friends and family huddled around Alcox and sobbed. “It was a joyous day,” he said.

The ruling upheld a verdict made last November by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit — second only to the U.S. Supreme Court in judicial clout — to dismiss Alcox’s case on the grounds that he received an inadequate defense at his original trial, a violation of his Sixth Amendment right. Magistrate Judge Andrew Wistrich also cited significant new evidence that spoke to Alcox’s innocence.

The Ninth Circuit didn’t exonerate Alcox, however, and the federal magistrates gave the Santa Barbara District Attorney’s Office the option to refile the murder charge within 60 days. They declined. By way of explanation, DA Joyce Dudley said in an email to The Santa Barbara Independent, “He already served his time, and he had been out awhile.”

But for Alcox and his legal team, actions speak louder than words. They think Dudley and her lawyers looked at the new evidence uncovered during his 16-year appeals process and finally realized they were beat. “You’re not going to let a guy go who you believe is truly guilty,” said Alcox. “You would at least put up a fight for the sake of the victim’s family.” Though his nightmare has ended, it continues for the family — many claim the real killer is still on the loose. “He’s still running around out there,” said Alcox.

Since being paroled in 2012, Alcox has concentrated on rebuilding his life. But that doesn’t mean he’s done fighting for what he’s lost — he’s preparing a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Santa Barbara and the state. Alcox’s supporters aren’t ready to forgive or forget, either. They want it publically known that their sweet-natured friend who loves God and his family suffered an irreparable miscarriage of justice. “The DA’s Office wants to keep this as quiet as they possibly can,” said Alcox’s close friend John Davis, a retired Raytheon engineer living in Goleta. “I’m here to do just the opposite.”

“This is one of the worst cases I’ve ever seen,” said Alcox’s defense attorney Juliana Drous. And she’s seen a lot. Based in San Francisco, Drous specializes in overturning wrongful convictions. Her victories have been widely publicized, including for Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt, a high-ranking member of the Black Panther Party who spent 27 years in prison for murder. Drous successfully argued that Los Angeles prosecutors had manipulated and concealed evidence at Pratt’s trial. She’s made similar allegations against Santa Barbara law enforcement.

“The facts of Joel’s case are amazing,” said Drous, who began representing him without pay in 2000. “How this ever happened in the first place is just unbelievable.”

•••

Life was never easy for Joel Alcox. He was born the youngest of nine siblings to a schizophrenic mother who was scared of aliens. His father died in a car accident before he was born. At age 8, Alcox was separated from his mother after the two were found wandering Riverside forests, eating bugs to survive. He was placed in six different foster homes and a boys’ home before the Alcox family finally adopted him at 14 and brought him to Lompoc.

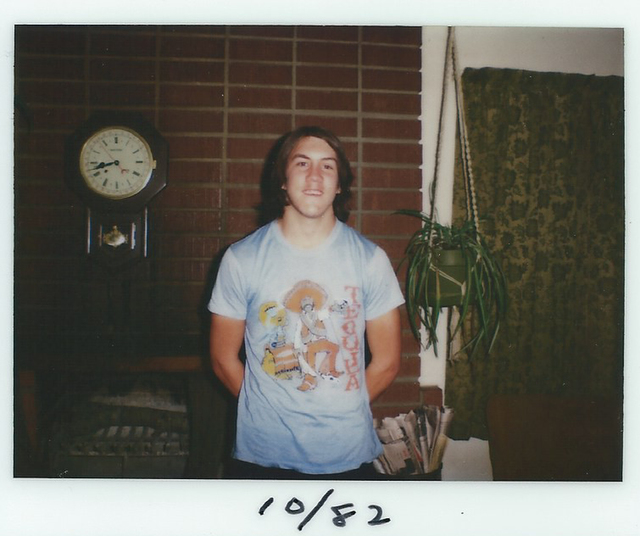

In high school, Alcox was quiet but well-liked. He had shaggy hair and crooked teeth. He played varsity football as a linebacker and defensive end, and he went camping and riding motorcycles with his brothers. He graduated in 1982, the same year he was baptized. Alcox immediately joined the U.S. Army, inspired by his late biological father, a U.S. Air Force veteran who served in Korea. He was stationed in Germany for two and a half years before being honorably discharged for drug and alcohol abuse.

Back home, his addictions spiraled. At the time, Alcox sang in a rock band, listened to Iron Maiden, and dreamed of breaking into the Los Angeles music scene. He refused to get a job or go into treatment. His parents kicked him out, and he spent months sleeping on friends’ couches. He was arrested for DUI and drinking in public but avoided any serious trouble with the law.

On February 16, 1986, at approximately 6 p.m., a man staying at the downtown Lompoc Motel heard shouting and then loud bangs down the hall. He peeked out his door and saw the motel’s owner, 49-year-old Thakorbhai Patel, slumped on the ground. He’d been shot through the left lung. The man asked Patel what had happened and who had shot him. Patel murmured, “Sanjo… Sanjo… Sanjo…” The guest ran to his room and called 9-1-1 as Patel staggered back to his small apartment attached to the motel’s front office.

Police found Patel collapsed on his living room floor, clutching a phone. The office cash drawer sat open and a crumpled $5 bill lay nearby. As paramedics and a firefighter rushed to his side, they heard Patel utter words that sounded like “Sanjo” or “Sanjay.” He died a few hours later at the hospital.

Five weeks went by. With a population of just under 30,000 and an economy on the upswing with the new Space Shuttle program at Vandenberg Air Force Base, murders were relatively rare in Lompoc, a rural community in northern Santa Barbara County surrounded by wildflower fields. Police were under increasing pressure to make an arrest but had few leads.

Then one day out of the blue, detectives received an anonymous tip that a “John Wilcox,” along with another young man named Ricky Lothery, killed Patel. Lead investigator Sergeant Harry Heidt pored over booking records and found that Joel Alcox had recently been arrested for public drunkenness. The name was close enough. Heidt went looking for Alcox.

On March 25 at around 9:45 a.m., Alcox was loafing around with a group of friends at the Lompoc Shopping Center. He had dropped acid the night before and was still high. He hadn’t slept or eaten, except for a quart of beer that morning. Heidt approached the group, asked for IDs, and singled out Alcox to ride with him back to the police station. Alcox asked why. Heidt said he’d tell him when they got there.

In a cramped interrogation room, Heidt and another investigator sat across from Alcox, nearly knee-to-knee. They asked where he was the night of February 16. Alcox said he was partying at a bandmate’s house. He remembered that evening clearly, he said, because they had planned to have a BBQ, but it rained. They stayed inside. Heidt told Alcox he didn’t believe him. He told him police knew he and Lothery killed Patel.

Alcox denied he had anything to do with the shooting. “I don’t know where you guys are comin’ from,” he said. “There’s no way I could have killed somebody.” He stuck to his story for hours, even as the LSD continued to wash over him — video of the interrogation shows him speaking rapidly and giggling oddly.

Eventually, Heidt and the other investigator leaned in closer and told Alcox they already had a mountain of evidence against him. They claimed Lothery, an acquaintance and the son of a Lompoc police officer, ratted on him, his fingerprints were at the scene, eyewitnesses put him at the motel, and his alibi didn’t check out. They hooked Alcox up to a polygraph machine and told him he failed two of their tests.

None of that was true. There was no testimony or physical evidence linking Alcox to the crime, but the police were relentless. They used every weapon at their disposal to get him to confess. Their tactics, though aggressive and dishonest, were legal — law enforcement is allowed to use what they call “ruses” to draw information from suspects.

“You know why we’re here,” Heidt said to Alcox. “Joel, it’s not going away …” After several more hours, Alcox — hungry, exhausted, and crashing from his acid high — started to question his own memory. Maybe he actually was at the hotel, he thought. Maybe he blacked out. He asked to be hypnotized to perhaps remember better. He combed the recesses of his brain for any recollection but found nothing. He only remembered being with his friends.

“That’s what I thought I did that night,” a visibly trembling Alcox said to Heidt. “Oh geez, I wish I knew. I’m telling the honest-to-God truth.” Heidt told Alcox to help himself and come clean. Don’t let Lothery decide your fate, he warned him. “You just wanna go down on first degree?” If Alcox admitted his guilt, Heidt promised, things would go easier. “We already know what happened,” he said. “What’ I’d like to know is did you plan to go in there and blow this guy away?”

By evening, Alcox was desperate to escape the two men in the tiny room. He believed he had no choice but to give them what they wanted. Alcox buckled and signed a written confession. It said he and Lothery had been drinking and decided to rob the motel. Alcox claimed he remembered Lothery pulling a revolver from his waistband and saying, “Let’s go get some money.” They walked past the motel and saw the office was empty, so Alcox muffled a bell above the door with his hand, entered the room, and opened the cash drawer, he said. When Patel suddenly walked in and confronted them, Alcox ran out. That’s when Lothery opened fire.

None of that was true, either. Almost all of the information contained in Alcox’s confession came from the police first — they drew a map of the motel for Alcox to describe the scene, showed him their service revolvers to get a description of Lothery’s gun, and so on. The few details Alcox offered on his own were inaccurate. Alcox said Patel was 5’11” with short hair. Patel was actually 5’4″ and mostly bald. Alcox said he heard two shots. Patel was fired at three times.

Nevertheless, with his hard-won confession in hand and the case all but closed, Heidt walked Alcox over to jail and booked him on charges of robbery and homicide. Police had their man. Nothing could convince them otherwise.

•••

It’s almost inconceivable that someone would admit to a murder they didn’t commit. But, as Alcox explained at Starbucks, his reason for self-incrimination was simple: “I didn’t understand what was going on,” he said, shaking his head. “I was overwhelmed, totally confused — and I wanted to get out of there.” When he finally did, he remembered thinking, “Fuck, what just happened?”

Though Heidt read him his rights, Alcox said he didn’t think he needed a lawyer. He knew he was innocent; he had faith Heidt would see that, too. He was close friends with another Lompoc cop and believed that the police never lied, that they cared more about catching the right person than closing a case.

As soon as Alcox got some sleep, ate a meal, and started thinking clearly again, he tried to recant his confession. But it was too late. The wheels of justice had started to turn. Nevertheless, he held out hope that prosecutors would figure out he gave a false statement, his lawyer would confirm his alibi, and the truth would set him free. “Obviously, that didn’t happen,” he said.

The court appointed defense attorney Ken Biely to represent Alcox. Prosecutors offered Alcox 15 years to life if he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. Alcox refused to lie on the stand. He’d take his chances with a jury.

Biely ran a law firm in Santa Maria at the time and was one of just a handful of private attorneys in North County with the resources to handle high-profile homicide cases. He had a reputation as a “tenacious and probing” lawyer, recalled clinical psychologist Dr. James Tahmisian, who testified for the prosecution in a number of Biely’s trials. “When Mr. Biely questioned me as an expert witness, I knew I was in for a rough time,” he said. Biely’s former colleague, attorney Richard Weldon, had similar recollections. “He was an honorable guy,” said Weldon. “I always thought he did a good job.”

If so, Biely’s defense of Alcox was far from his finest hour. The Ninth Circuit found Biely, who died in 1993, utterly incompetent. He performed “no investigation whatsoever” prior to Alcox’s trial and met his client in jail just once before proceedings began. From then on, he relied almost exclusively on the District Attorney’s Office for discovery and information in the case. Overall, his “so-called defense” was “factually far-fetched” and “legally unsupportable,” Magistrate Wistrich stated in his ruling.

Most bizarrely, Biely told jurors — in closing arguments, no less — that Alcox’s confession was true, that he entered the motel with the intention of robbing it. “I know that looks bad,” he said, according to court transcripts. But Biely claimed his client fled before any shots were fired. Even if that sequence of events were accurate, Biely’s admission condemned Alcox under California’s felony-murder rule, which makes a defendant guilty of murder if he or she or a fellow perpetrator kills someone while committing a felony, such as burglary.

“His closing argument essentially sealed the deal,” said Wistrich, who disagreed with previous state court rulings that Alcox wasn’t allowed to “second-guess” his attorney’s “strategy.”

When Juliana Drous and her investigator opened Biely’s mothballed case file 13 years after the trial, they were shocked to find he had not interviewed any of Alcox’s friends who would have confirmed his alibi of being at his bandmate’s party at the time of the shooting. Instead, Biely took the DA’s Office at its word that the witnesses were unreliable and could easily be impeached on the stand.

Drous and her colleagues spent the next few years tracking down Alcox’s friends, now spread across the country — Sean Daugherty in Tennessee, Charles Robb in Missouri, Roberta Ude in Los Angeles, Birgitte Barker in Florida, Kathleen Webb Schmidt in Lompoc, and so on. Every one of them said the same thing: Alcox was with them the night of the shooting. He couldn’t have killed Patel.

Biely also failed to argue against two of the prosecution’s key pieces of evidence. One was the trial testimony of a 15-year-old Lompoc girl named Caroline Gonzales, who claimed to have overheard Alcox admit to the murder during a late-night conversation with one of her friends in an alley behind the Alcox family home. Biely chose to not cross-examine Gonzales, instead writing a single line in his file: “Caroline Gonzales is simple minded and should be disregarded.”

In 2006, Drous located Gonzales living in Washington State. Gonzales said she now believes the details of that back-alley conversation were a figment of her imagination. She was a heavy drug user at the time. She didn’t want to admit that to police and recant her statements. “I do remember I was on LSD, and I was scared to say that,” she told Drous. “Because I certainly didn’t set out to lie.” Gonzales broke down in tears when she learned her statements helped keep Alcox behind bars.

Gonzales thinks she actually heard her friend speaking with John Alcox, Joel’s older brother. Gonzales remembered police first suggested the name “Joel” to her and that she only picked him out in court because she knew that’s who prosecutors wanted her to identify. It was Gonzales’s mother who left the anonymous tip with Lompoc police that Lothery and “John Wilcox” had shot Patel.

In addition to Alcox’s false confession and Gonzales’s untruthful testimony, lead prosecutor Christie Stanley relied heavily on portions of a jailhouse conversation between Alcox and Lothery to convince the jury of his guilt. At trial, a Lompoc jailer named Carol Seilhamer testified that the morning of March 27, shortly after Lothery was arrested, she overhead the two speaking to each other through a ventilation shaft connecting their cells.

“Joel, we’re in a lot of trouble,” Lothery said. “You really fucked us by giving that statement to police.” Alcox responded, “They don’t have any fingerprints, and they don’t have the gun. The only evidence they have against you is my statement, and I’m going to say it was a false statement.” Alcox also told Lothery his friends would tell police that he was with them the night of the shooting. Everything would be cleared up soon, Alcox promised.

In her closing arguments, Stanley recounted the conversation and argued the men were concocting a fake alibi. She asked if they weren’t, wouldn’t Lothery be furious with Alcox? “Don’t you think that if he were not responsible for this murder, that would have been the perfect time for him to say, ‘You absolute idiot. You crazy liar. What are you telling these people?’” she asked. “But you heard none of that in this jail conversation because it didn’t occur.”

But it actually did occur. Unlike Biely, who did not cross-examine Seilhamer, Drous listened to the full recording of the men’s conversation. Lothery was livid. “I just can’t fucking believe why you would make up that story,” he said to Alcox. “I can’t understand how you got yourself into this.” Alcox explained he was high and scared. “I was freaking, man. … I was under pressure. I didn’t have much sleep, and I wasn’t thinking right.”

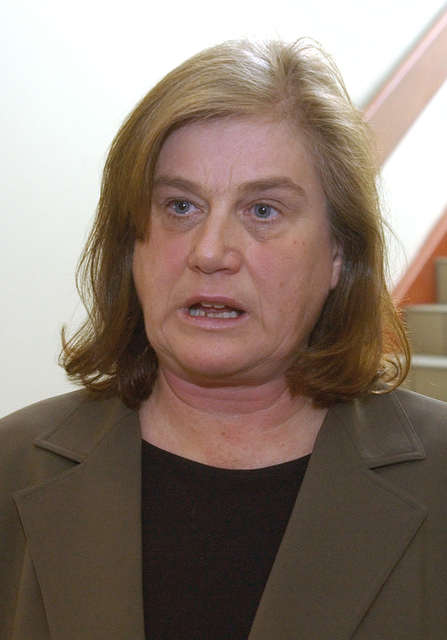

For Stanley to intentionally misrepresent the pair’s conversation, to take a portion of it out of context and manipulate its meaning for the jury, is unconscionable, said Drous. What’s worse, she claimed, Stanley — who was elected District Attorney in 2006 and died of lung cancer in 2010 — withheld evidence that points to the identity of the real killer. “The District Attorney’s job is to get justice,” Drous said. “It’s not to get convictions.”

•••

Sanjay Patel went by the nicknames “Jay” and “Sanjo.” He was a close family friend of Thakorbhai Patel; Sanjay’s father and Thakorbhai did business together. Despite their shared last name, they were not related.

On April 11, 1987, more than a year after Thakorbhai was shot and killed but before Alcox’s trial, Sanjay called 9-1-1 from his parents’ house. “Jay Patel. I’m ready to go in for the murder,” he told the operator. “I’m ready to confess to murder. Lompoc Motel.” Then he hung up. Police traced the call and brought Sanjay in for questioning.

During his interview with Sgt. Heidt, Sanjay, who smelled of alcohol and appeared drunk, immediately demanded a lawyer but continued talking. His statements were rambling and suspicious. He asked Heidt if he was a father, and what he would do if his son committed murder. “I hope I was drunk enough even if I did commit a murder,” Sanjay said before going quiet. Without more evidence against him, Heidt terminated the interview and released Sanjay.

The recording of that interview never made it to Biely’s file. Drous only heard it when she petitioned the District Attorney’s Office for copies of all tapes related to the case. Drous asked Lothery’s original trial attorney James Voysey if he had received the recording as part of the pretrial discovery process. That’s when the prosecution is required to turn over all relevant evidence to the defense. Voysey said he did not.

Shortly after Alcox was convicted in 1987, Lothery was, too. Voysey provided his client a complete and competent defense, trial records show. He is now a judge in Santa Maria.

If Stanley intentionally withheld the tape from both Biely and Voysey, it would amount to a massive breach of authority, Drous said. “That’s gross misconduct,” she said. “That’s horrible misconduct.” In 2005, Drous filed a formal request for information from the District Attorney’s Office about whether the recording was ever turned over to the two defense attorneys. The DA’s Office never responded to that request.

There is an array of other evidence implicating Sanjay, Drous continued. Some of it was presented to the jury during the original trial. Much of it wasn’t. At trial, Sanjay’s former girlfriend Junia Fritz testified that on the night of the murder, Sanjay came to her apartment. He took a handgun from his waistband and told her to hide it. One of Sanjay’s friends, Mike Coleman, later told police that Sanjay “bragged” about the shooting on multiple occasions, disclosing a detail only the killer would have known — one of the three bullets fired at Thakorbhai Patel ricocheted off a ring on his hand and lodged in his jaw.

Sanjay was never charged or arrested for Thakorbhai’s murder. Some years after the shooting, he moved to London, where Drous’s investigator reached him by phone. “That was a long time ago,” Sanjay told the investigator. “Things are different now.” He declined to speak any further.

Lothery was sentenced to life in prison, where he remains. For a long time, he stayed furious at Alcox for implicating him in the shooting. At one point, he put a bounty on his former friend’s head. When Drous contacted him in 2000, he refused to help.

But after a number of phone calls and letters — and a personal visit from Alcox’s aunt — he changed his mind. “I could cut Joel loose,” Lothery said in a letter to Drous. “He wasn’t even there,” though Lothery said he would never understand why Alcox gave a “bogus confession” to police.

In a signed 2003 declaration, Lothery wrote what he says really happened that night: Lothery had been drinking with a group of friends when he met up with Sanjay at Thrifty’s in the Lompoc Shopping Center. Lothery told Sanjay he was going to steal more alcohol, but Sanjay suggested they instead try and sell a power drill he had in his bag to Thakorbhai, whom he referred to as “uncle.” Inside the motel office, Sanjay and Thakorbhai started arguing in a language Lothery said he could not understand. As the dispute escalated, Thakorbhai took a $5 bill from his cash register and threw it at Sanjay. Sanjay drew a gun from his waistband and fired.

“Joel Alcox has served 18 years for Sanjay Patel’s crime,” Lothery wrote. “Joel Alcox was not there.” Lothery said he had no reason to lie — by admitting he was with Sanjay during the shooting, he was condemning himself to the life sentence he was already serving. “I have nothing to lose and nothing to gain by telling the truth,” he wrote.

“The more this sits on my mind, and the more I read these transcripts, the more I understand that this was a tragedy,” he said to Drous in a phone call. He wished Alcox the best, “because he got the worse end of this whole situation.”

•••

By the time the jury returned with Alcox’s guilty verdict in 1987, he’d been in County Jail for 16 months. He’d already given up. The shame paralyzed him. “I was embarrassed that I had made this false confession,” Alcox told me. “I was embarrassed no one would believe me.” He became a fatalist with no control over his destiny. “I basically thought, ‘Whatever’s going to happen is going to happen,’” he said. “‘Do whatever you want with me.’”

Like anyone in prison, Alcox had to watch his back. “It’s survival,” he said. He saw people die by stabbing, shooting, and disease. He had few visitors. Eventually, Alcox fell into a routine. He lifted weights, read the bible, took theology classes, and toiled in a maintenance shop. A religious man even before he went away, Alcox said it was his Christian faith that kept him going. “I still had that hope,” he said.

Time passed slowly. Alcox kept himself distracted, but he feared he would die behind bars. “There are times when you’re just … you literally cry yourself to sleep.”

Many inmates are forced to join gangs for protection. Alcox avoided that though came close. While at Folsom State Prison, a member of a black gang stabbed a member of a white gang. The white gang leader passed around a hat and demanded every Caucasian man put his name in. Whoever was picked had to retaliate or suffer the consequences. But when the hat got around to Alcox and the other “bible-thumpers,” as they were called, the gang boss gave them a pass. “I guess he saw something in us and thought, ‘That ain’t right,’” Alcox mused.

A few years later, Alcox, whose family birth name is Tissue, started searching for his birth mother and the rest of her family. Maybe one of them would take an interest in his case, he thought. “But I didn’t want to use people,” he insisted. His adoptive mother helped connect him with a cousin named Sharon Tissue, a historian for the Tissue family, whose Pennsylvania lineage goes back to the 1600s and the American Revolution. Alcox wrote Tissue a letter. He told her his story but didn’t ask for help. Still, his message made her nervous. She didn’t reply for six weeks.

When Tissue finally wrote back, she gave Alcox the third degree. She asked him about every detail of his case. Before long, she believed him. Tissue contacted her pastor, who spoke with an attorney, who connected her to Drous. “I prayed about it,” she said. She organized a list of more than 200 friends and church members who also prayed for Alcox. They sent him small gifts. “Joel is a blessing in our lives.”

John Davis met Alcox at Santa Barbara County Jail in 2003 during one of his many appeals hearings. Davis’s mother, a close friend of Sharon Tissue, had heard about his case and asked her son to pay a visit. Davis was won over, too. They talked about sports and life. “He’s very disarming,” Davis said, “a very gentle soul.” When Alcox was paroled in 2012, he lived with Davis and his wife, Lisa, in their guest room in Goleta. “You can imagine that conversation,” he said. But Davis trusted Alcox, and soon Lisa did, too.

They cooked him filet mignon and introduced him to cell phones. As a parolee, Alcox had weekly urine tests and a strict curfew. For 18 months, he worked as a carpet cleaner and then as a Vons stock hand before moving down to the San Bernardino area. Davis knew it was just a matter of time before Alcox’s case reached higher courts and his sentence was overturned. “Federal courts are the adults in the room,” Davis said. “State courts are elected officials who spend most of their time trying to stroke each other and save face.”

James McCloskey with Centurion Ministries in New Jersey took up Alcox’s cause in 2008. The founder and director of the New Jersey organization that petitions on behalf of prisoners it believes were wrongfully convicted wrote a letter to Governor Jerry Brown, pleading with him to review the case. McCloskey said Alcox’s claim of innocence was “among the most compelling I have encountered in the nearly three decades of doing this work.”

McCloskey called the “deathbed utterance” of Thakorbhai Patel the most convincing piece of evidence of Sanjay Patel’s guilt — two paramedics, a firefighter, and a motel guest all heard Patel say the words “Sanjo” or “Sanjay.” McCloskey also noted how surprisingly common false confessions are — 25 percent of prisoners exonerated by DNA had wrongly confessed to the crime for which they were convicted.

Accompanying Alcox’s petition to the Ninth Circuit court was a report written in 2001 by Dr. Richard Leo, professor of psychology and law at the University of San Francisco and a nationally recognized authority on police coercion and false confessions. Leo conceded that the phenomenon of false confessions may seem irrational, if not impossible — unless a person is tortured or raving mad, why would they ever admit to a crime they didn’t commit, especially if they knew doing so meant a lengthy prison sentence?

To understand why that happens, Leo wrote, it’s necessary to know that interrogations are specifically designed to manipulate a suspect’s perceptions and decisions. And interrogations — as opposed to interviews of victims or witnesses — are meant for the guilty, not the innocent. Police go in thinking they’ve caught the right person. Their goal, and their job, is to elicit an incriminating statement that confirms that belief.

Investigators work to erode a suspect’s resistance — they attack his alibi, dismiss his denials, confront him with seemingly irrefutable evidence (whether real or made up), and convince him that he is caught, that no one will believe he is innocent. They try to persuade their suspect that, given the circumstances, confessing will improve his otherwise hopeless predicament; admitting his guilt will look good to a judge and jury.

All of these tactics were on display during Alcox’s interrogation, Leo said. While the methods are legal, they’re risky, especially if used too aggressively on a suspect who is young, has a low IQ, or is under the influence of drugs or alcohol. In those instances, the suspect’s reasoning system becomes so warped that logic melts away. Leo called Alcox’s interrogation “highly coercive” and said it had every hallmark of a police grilling that can, and does, lead to a false confession.

Magistrate Wistrich and the Ninth Circuit agreed there existed strong evidence of coercion. “When [Alcox’s] answers did not conform to the facts as the officers believed them to be,” the federal court wrote, “they inquired further until they got an answer that fit with the evidence.”

Leo told The Independent that back in the 1980s, academics had a good understanding of false confessions, but criminal defense attorneys, police, and prosecutors did not. (Police and prosecutors still don’t, he said.) It was common practice at the time for defense attorneys, representing clients who had confessed, to base their trial strategies on the belief that their client was indeed culpable and had already admitted his guilt.

Law enforcement tends to remain in stubborn denial whenever they lock up an innocent person. “They almost never admit that anything they did contributed to a wrongful conviction,” Leo said, “and they almost always insist that the confession was true, even when the evidence clearly indicates the opposite.” Honest mistakes can happen, he agreed, but the only way law enforcement should be forgiven for miscalculations that wreck such devastating consequences is if their department takes a hard look at what went wrong.

In Alcox’s case, Leo continued, the Lompoc Police Department and Santa Barbara District Attorney’s Office should also “push to make sure Mr. Alcox receives appropriate compensation for his wrongful conviction and deprivation of liberty, which they caused.”

•••

Alcox doesn’t expect police or prosecutors will ever admit they made a mistake or apologize. “I’m not holding my breath,” he said. Sgt. Heidt did not return requests for comment for this story. Current Lompoc Police Chief Pat Walsh declined an interview. Other law enforcement officials quietly defended Heidt’s investigation but would not speak on the record.

In a 2004 interview with the Lompoc Record, Lothery’s defense attorney Voysey said he believed Alcox’s confession was false, but that the police didn’t intentionally frame the wrong man. “In my experience, Harry Heidt is not the type of guy who would coerce a confession out of anybody,” Voysey said. “He’s well-respected.”

Even in hindsight, DA Dudley stands by the verdict. “After numerous state and federal appeals and writs of habeas corpus filed by Alcox,” she said, “no court has made a finding of actual innocence, nor has Alcox presented any new evidence indicating actual innocence or evidence that undermines our confidence in the conviction.”

Dudley pointed to the 2005 ruling of Judge Arthur Garcia in Santa Barbara Superior Court, the first stop in Alcox’s long journey through the appeals process. Although Garcia found that Alcox had received ineffective legal counsel — which overturned his conviction and ultimately paved the way to his freedom — he called evidence of Alcox’s innocence unconvincing. Lothery was not a credible witness, he said. Neither was Gonzales.

Dudley spent weeks after the May 11 hearing reviewing Alcox’s case and his interrogation. “We concur with Santa Barbara Superior Court Judge Garcia’s finding that ‘the confession of Joel Alcox was freely and voluntarily given,’” she said, “and that ‘it was not the product of coercion.’” State courts ultimately reversed Garcia’s decision, prompting Alcox to petition the Ninth Circuit court.

So while her office chose not to challenge the federal magistrates’ final ruling to overturn Alcox’s conviction, Dudley concluded, “We stand by our decision to prosecute because Alcox freely and voluntarily confessed to his role in the murder.”

Alcox and his legal team still can’t wrap their heads around this. “So what changed since 1986?” Alcox asked. “A mountain of evidence that has been put in front of their faces, and now they have to deal with it.”

Alcox tries not to dwell on the investigator who allegedly coerced him into a false confession or on the prosecutor who purportedly misled the jury to secure a conviction. He even manages to stifle bitterness toward the defense attorney who failed him so miserably. “But there’s a lot of pain there,” he said.

Sometimes Alcox fantasizes about confronting Heidt and telling him to his face: “You’re a liar.” “But stuff like that isn’t going to do any good,” he said with a shrug. “I know I have my freedom, that they have no hold over me anymore.” Still, Alcox can’t hide his anger for Stanley and what he called the “twisted” methods she used to put him in prison.

In a strange coincidence, Alcox had been at Stanley’s house more than once before he was arrested — her daughter dated his brother. Alcox remembered her making rude remarks to him and others at the time. “I thought of her then as an arrogant bitch,” he said. “And that’s how I still regard her.”

Stanley had a reputation as a tough, tenacious prosecutor. She graduated first in her class from the Ventura College of Law and practiced private civil law for two years before joining the Santa Barbara District Attorney’s Office in 1980. She often said the murder of her uncle in Kansas inspired her to join law enforcement. Stanley was the first female lawyer to work for the DA’s North County office, where the majority of Santa Barbara’s most serious violent crimes are prosecuted.

Stanley started campaigning for DA in 2005, the same year Garcia overturned Alcox’s sentence. She argued strongly and successfully against his release. Thakorbhai Patel’s family donated $5,000 to her campaign, which was one of the largest contributions she received, finance records show. She beat two other candidates and was elected in 2006 with an overwhelming 69 percent of the vote.

Stanley served as DA for less than two years before her cancer forced her into retirement. Longtime colleague Josh Lynn remembered her as a “wonderful, giving, honest human being.”

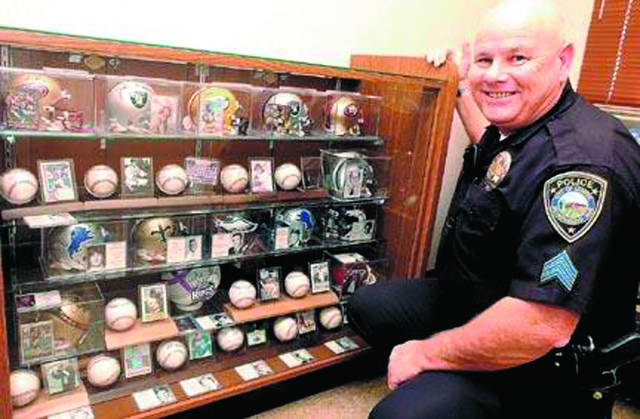

Heidt retired as a sergeant in 2004 after a decorated 33-year career in law enforcement, though he continued to work part-time as an investigator. Attempts to reach Thakorbhai Patel’s family have not been successful. Detectives have no plans to pursue Sanjay Patel.

It remains a mystery why police and prosecutors became and stayed so fixated on Alcox. He thinks it was political. It would have certainly hurt Stanley’s chances of becoming DA if a high-profile murder conviction was overturned in the midst of her campaign. Dudley won’t admit a killer remains free, as that would hurt her chances for reelection, he said.

Drous had a much simpler explanation: “This wasn’t a conspiracy,” she said. “It was just incompetency at the highest levels.”

•••

Even after Stanley’s death, the DA’s Office fought hard to keep Alcox behind bars. For a parole hearing in 2012, Dudley dispatched Ann Bramsen, one of her top North County prosecutors, to Avenal State Prison, around 80 miles northwest of Bakersfield. Rather than focus on the facts of the case, Bramsen attacked Alcox’s character. She called him a drug addict and a liar. She said he was a coward with “delusions of innocence.”

Alcox was a model prisoner for 25 years; he didn’t receive a single disciplinary citation. He took general education college courses, as well as Spanish and French, and taught himself a little German, too. Last February, Alcox graduated from online college Ashford University with a BA in applied linguistics. He’s now looking at master’s degree programs and wants to one day teach linguistics at the college level. Ancient Greek, a biblical language, interests him the most.

In the meantime, Alcox works hard to make ends meet. He’s on the road six, sometimes seven, days a week, delivering tires around the Inland Empire. It’s backbreaking, but he’s grateful. Alcox still savors every small moment and sensation of the outside world, like the weight of silverware and sleeping with the lights off. He’s still impressed by motion-activated sinks and the variety of sugar packets at restaurants.

Alcox loves spending time with his wife, whom he met online two years ago, and his two stepdaughters, the older of whom is deciding where she wants to go to college. He reads and writes a lot of fiction and hopes to eventually publish a book about his life. Now that his criminal case has ended, he’s exploring his options for civil litigation. “But how do you put a dollar figure on life?” he asked. “Time is priceless.” On the other hand, “a million dollars per year in prison sounds like a good place to start,” he said.

Much of Alcox’s remaining angst evaporated with the May 11 ruling, and despite what he’s been through, he beams positivity. “I can’t carry that burden around with me and live a happy life,” he said. His freedom is still hard to fathom, and it may not fully sink in until he travels out of state, which he hopes to do soon. “I can go anywhere I want!” he exclaimed. “And I don’t have to ask anybody. I just go.”

Alcox recalled one of his many trips in a prison transport van: “I remember seeing weeds go by on the side of the road and wishing so badly I could just go walk in them,” he said. The other week, Alcox was stuck in traffic when he saw a small field of dry grass out the window. “I just stared at it,” he said. “I thought to myself, ‘I could literally just stop my truck, get out, and walk into that.’ That freedom is there.” He feels lucky to appreciate those fleeting joys. “It’s a gift most people don’t have,” he said. “It’s wonderful.”