Life in the Commons with the Homeless Population: Part 1

Human Rights and Human Foibles Present a Challenge

City discussions about the future of State Street miss the mark unless they focus on the homeless problem. Making State Street a walking mall, promoting mixed-use commercial-residential, lowering rents, and expediting permits for new business are all very good ideas. However, until we figure out how to deal with the incredibly difficult and tragic problem of the homeless, the decline of State, I’m afraid, will continue.

Cities throughout the U.S. are experiencing an increase in people without homes who are interacting with fellow citizens in the “commons” (common areas). The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development statistics showed nearly 554,000 homeless across the country in 2017 (134,278 in California, with some 55,000 in Southern California), up one percent from previous years. Of these, approximately 193,000 have no access to nightly shelter and are living in vehicles, doorways, tents, on the streets, beaches, and adjacent to railroad tracks.

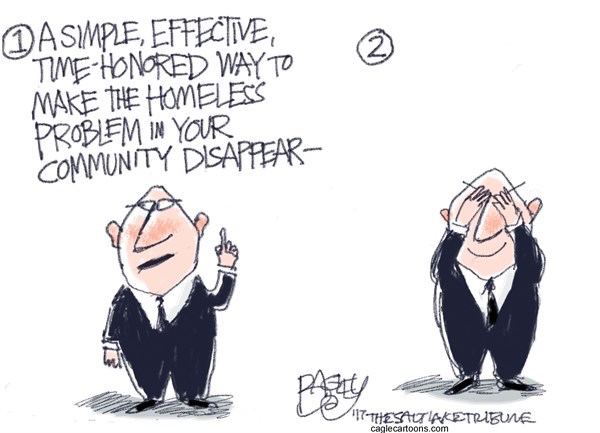

In Santa Barbara County the numbers fluctuated between 1,536 in 2011, to 1,489 in 2017. The most recent survey found 790 homeless people in Santa Barbara, with 363 living unsheltered and 427 living in nonprofit or government shelters. Unsheltered or sheltered, the homeless have become our neighbors. They are not going to disappear. Unless and until we resolve how to integrate these citizens into the commons, i.e., State Street and its environs, the city will continue to experience lost tax revenue from State Street stores (needed for such public services as education, parks, police, and fire) and declining participation by residents and visitors in the State Street experience.

State Street is the face of the city. At last count there were 38 vacancies on State. All manner of tenants, including Saks, Macy’s, Panera, Pierre La Fond, Blush, Bucatini, Aaron Brothers, Goorins, K-Frank, Design Within Reach, and Staples, have closed up shop and left. It’s simply hard to believe that all of these different kinds of business have left just because of high rents or e-commerce. Current research suggests that people across the country are still making their way to retail stores because they want to have actual physical interactions. The kind that don’t exist on the internet. People want the experience of physically participating in the dynamic of the commons.

The homeless, too, are drawn to the commons. They see it as a living space, a place to make money by panhandling and pilfering cash-worthy recyclables from city receptacles, a place to live (which includes spending daylight hours socializing, resting, reading, sleeping, entertaining themselves, and relieving bodily functions). If we’re honest, homeless socializing is essentially no different from the other socializing that goes on among people on State. Where the behavior breaks down and where it can become frightening is in aggressive panhandling, living in public, intrusions into personal space, unkempt appearance, and outbursts which are very different from the way people normally look and act when out in public.

To say the least, the problem is profoundly complicated. People living on the street are displaced persons without the stability of having a home and are deserving of compassion. They also have legal rights that allow them to ask for money, and if the city doesn’t have enough beds, to sleep on the street. (The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal recently ruled that unless beds are available, it is “cruel and unusual punishment,” violating the Eight Amendment, to prosecute people for sleeping on the street.) On the other hand, homeless behavior is often deviates from social norms.

My wife and I lived downtown for five years, just off State Street. We witnessed homeless people defecating and urinating behind our home, dressing at the curb in front of our home, barbecuing at a bus stop, masturbating, arguing and fighting with each other, soliciting for money, and barging into restaurants and threatening people. It got to the point that my wife no longer felt safe going out alone.

This kind of aberrant behavior was also experienced by neighbors and has been reported by State Street merchants. (And, in April a homeless man killed a patron at the Aloha Steakhouse in Ventura, who was seated with his daughter on his lap while having dinner with his family). This is not the kind of behavior that is tolerated in the commons.

Cities have always had common places. These places have always been characterized by commercial and recreational facilities. Historically, such common places developed norms of behavior, a social etiquette allowing different kinds of people to mingle. When these social norms were violated, the etiquette was restored by law enforcement.

To fully understand the sociological problem of people without homes living among us, we have to look back to the 1980s when the Reagan administration slashed federal funding for public housing and Section 8 by half, and repealed a law that would have continued funding federal community health centers. These actions created an explosion of people, including the mentally impaired, having to live on the street. Factoring in the economic downturn of 2008, decreased funding for housing assistance, and the fact that the homeless are not a homogenous community, and the magnitude of the problem becomes apparent.

The homeless population consists of several very different kinds of people: resident homeless, mentally ill homeless, substance abusers, adult transient homeless, and youth transient homeless. Many need social services assistance, which are provided by the county and city, for instance, shelters, hot meals, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, medical and dental services, and overnight parking for those living in vehicles. Especially effective have been the Pescadero housing project in Isla Vista, funded by the federal government and the county Housing Authority (and provides not only housing but also mental health services, alcohol and drug addiction counseling, computer and financial literacy classes, and job training); Johnson Court in the City of Santa Barbara, being built to serve the homeless veteran population; and the award-winning city Housing Authority, which provides affordable rental housing for low-income families and elderly and disabled persons). These are all good, humane, necessary things that should be supported and expanded. It also means that given these services and Santa Barbara’s temperate weather, the homeless problem is not going away.

The homeless are now our neighbors. We have to figure out how to ensure their rights while preserving the sanctity of the “commons.”