Sisters Say Brother Sick with COVID-19 Was Released from Lompoc Prison to Die

Local Prison Outbreak Worst in United States; Inmate Families Desperate for Information

Efrem Stutson was excited to go home. He had served 27 years of a life sentence for selling cocaine in northern Alabama, but he was getting out early under a new federal prison reform aimed at low-level drug offenders. Stutson, 60, talked to his sister Lawanda Rangal a week before his April 1 release. “He sounded happy,” she said. “He sounded relieved.”

But as the date approached, Rangal said, Stutson got sick. Very sick. “He could barely talk,” she said. Stutson had spent the last six months of his sentence working in the kitchen at United States Penitentiary Lompoc (USP Lompoc), where a severe COVID-19 outbreak is now spreading unchecked among inmates and staff.

Despite Stutson’s condition, which included a bad cough, Rangal claimed, USP Lompoc sent him packing on a Greyhound bus bound for San Bernardino. Their sister, Laura Harris-Gidd, met him there. “He was so out of it,” Harris-Gidd said. “He could hardly hold his head up.” Stutson refused to go to the hospital that night, but the next morning his family insisted. Paramedics wearing protective equipment rushed him to Kaiser Permanente medical center in Fontana. Doctors diagnosed him with COVID-19 and put him in quarantine. No visitors were allowed. Four days later, Stutson died.

Rangal and Harris-Gidd are heartbroken — and furious. “Why did they release him so sick?” asked Rangal. “They sent him home on his deathbed.” She wishes she could have gotten to know her older brother again, remembering that when they picked out bikes as kids, he wanted her to have the best one. Stutson paid his debt, Harris-Gidd went on. He deserved better. “You spend so much time incarcerated, so many days taken from you…,” she said, trailing off. “He never got the chance to experience the goodness of life in his children and grandchildren. He didn’t even get to enjoy a decent meal.” The family is now considering their legal options.

Worst in the U.S.

As of Wednesday, April 15, 69 inmates and 24 staff at USP Lompoc have tested positive for COVID-19, more than any other correctional institution operated by the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). With Santa Barbara County reporting 313 COVID-19 cases, the penitentiary now accounts for a full 30 percent of the region’s total.

Thirteen of the infected inmates are hospitalized. Eight are being cared for at Lompoc Valley Medical Center (LVMC) and five at Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital. Six are on ventilators. One staff member is hospitalized. “Lompoc Valley Medical Center, and the other hospitals within the county, are able to manage the present number of inpatients coming from the penitentiary,” said LVMC spokesperson Nora Wallace. “However, the hospitals and governmental entities are making significant contingency plans with the expectation that the number of patients will increase before it decreases.”

Hospitalized inmates are guarded 24 hours a day by two prison officers, who rotate on eight-hour shifts. To lessen the load on regional medical centers and to better accommodate the security measures necessary for inmates, Lompoc prison officials requested a 50-bed mobile hospital from the BOP, but they were told by their national office it could take four to six weeks to arrive.

The BOP has been resoundingly criticized for its response to the numerous outbreaks at their facilities, with inmates and their families ― as well as guards, who feel they’ve been unfairly put in harm’s way ― calling the containment efforts too little too late. So far, 446 inmates and 248 staff are confirmed infected; 14 inmates have died. The agency initiated its most restrictive measures on March 31, which included keeping prisoners in their “assigned cells or quarters” for 14 days and stopping all transfers between facilities. Officials said they would reevaluate the order after 14 days, but 15 days later, no decision has been announced.

Over the past week, family members of Lompoc inmates have contacted the Santa Barbara Independent with serious concerns for the safety of their relatives. Many are just desperate for information. “I have a son housed there and we are in constant contact 2-3 times a week,” said Susan Morsen in an email. “I have not heard from him in over 3 weeks. He also has acute bronchitis and other medical issues. I have not been able to obtain any updates from anyone at USP Lompoc to find out if he is ok.”

The wife of a longtime inmate, who wished to go by the name of Lavonne, said when she called the prison on Monday, an Officer Perridon answered and said he couldn’t provide her with any information. When Lavonne asked to speak to James Engleman, the acting warden, Perridon reportedly laughed, told her she might as well ask to talk to the president, and hung up.

Families have also provided the Independent with emails and letters sent to them from inside the penitentiary. The messages paint the picture of an institution overwhelmed and underprepared. “The BOP is not being transparent to the public about what is happening behind these walls,” one note reads. Most of the sources requested anonymity for fear of reprisal from prison officials.

Social-distancing orders simply aren’t possible in a prison setting, the Lompoc inmates stressed. One said he bunks in a single large room with 230 other offenders who sleep within three feet of one another. Hand sanitizer ran out weeks ago, and soap is in short supply. Many have wondered why, despite an April 3 order from Attorney General William Barr for all 122 BOP facilities to thin out their low-risk populations with home confinements, the Lompoc prison hasn’t tried to do so.

Guards, officers, nurses, and other staff rarely wear gloves or masks when working, the inmates allege. The staff themselves are frustrated, with some complaining that basic protective equipment came to them well after the virus started spreading, and even then in inadequate quantities. Guards have also protested being forced to work in the Lompoc prison’s quarantine area, which has taken over its Segregated Housing Unit, or SHU, a grouping of high-security, single-occupancy cells normally reserved for violent inmates.

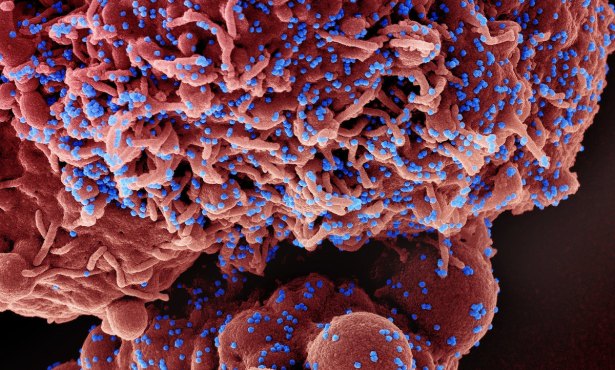

On March 30, the American Federation of Government Employees, the national union representing 33,000 BOP correctional workers, including those in Lompoc, filed a class-action lawsuit demanding hazard pay. “Federal prisons are already dangerously understaffed, and now they are a petri dish for COVID-19,” said Heidi Burakiewicz, at attorney representing the union, in a statement.

Phone Minutes and Masks

Santa Barbara County health officials say they are coordinating with BOP authorities to address the outbreak. “Our team has been in very close communication with the Lompoc prison,” said Dr. Van Do-Reynoso, director of the county’s Public Health Department, at a media briefing last Thursday. She said the county has made its Care Center in Lompoc available to penitentiary staff for testing, and her team is providing guidance on “how to stand up a medical center on their grounds.” Do-Reynoso also said that if the prison needed additional resources, “we will be the ones to facilitate those material requests.”

Emery Nelson, a BOP spokesperson, said the agency understands “these are stressful times for both inmates and their loved ones.” He said prison officials are taking all the necessary precautions and following Centers for Disease Control guidance to maximize social distancing among inmates populations.

In contrast to the claims of Lompoc inmate families who say they can’t reach their relatives inside, Nelson said mail is being distributed daily. “We encourage inmates and family to write to one another often,” he said. “To further assist inmates to communicate with their loved ones and friends, we have increased the monthly phone minutes per inmate from 300 to 500 per month.”

Nelson confirmed that Efrem Stutson was released on April 1. But for “privacy, safety, and security reasons,” he said, he could not comment on Stutson’s medical condition at the time. “All inmates, prior to releasing from the BOP, will be screened by medical staff for COVID-19 symptoms,” he said. “If symptomatic for COVID-19, the institution will notify the local health authorities in the location where the inmate is releasing, and transportation that will minimize exposure will be used, and inmates will be supplied a mask to wear.”

Laura Harris-Gidd said Stutson wasn’t wearing a mask when she picked him up from the Greyhound bus station. “I just don’t understand why they would let him out instead of quarantining him and taking care of him,” she said. “I think they’re hiding a lot.”

This article was underwritten in part by the Mickey Flacks Journalism Fund for Social Justice, a proud, innovative supporter of local news. To make a contribution go to sbcan.org/journalism_fund.

You must be logged in to post a comment.