No ‘Silver Bullet’ Can Solve the Homelessness Problem

Governor Newsom Has Provided Funding to Address the Issue

California is home to more than a quarter of the nation’s homeless population. There are an estimated 161,548 homeless living on our streets. A recent poll by the Public Policy Institute of California found that likely recall voters ranked homelessness as the third most important issue in California, after jobs and COVID-19. John Cox, Kevin Faulconer, and Larry Elder, among other Republican candidates, have picked up on this issue in their bids to unseat Governor Newsom. Because of the prevalence of homelessness, and tent encampments in our cities, it could dominate the recall election.

There are three things to understand in evaluating this issue: The Republican candidates are promoting one-dimensional talking points, Governor Newsom’s homeless legislation is comprehensive, and there is no “silver bullet” that can solve the problem.

The homeless have become our neighbors. Their population consists of several very different kinds of people composed of resident homeless, mentally ill homeless, substance abusers, adult and youth transient homeless. They have legal rights that allow them to ask for money, and if a city doesn’t have enough beds, to sleep on the street. Voters need to understand there is no one solution to addressing, much less solving, the issue of homeless people sleeping on the streets.

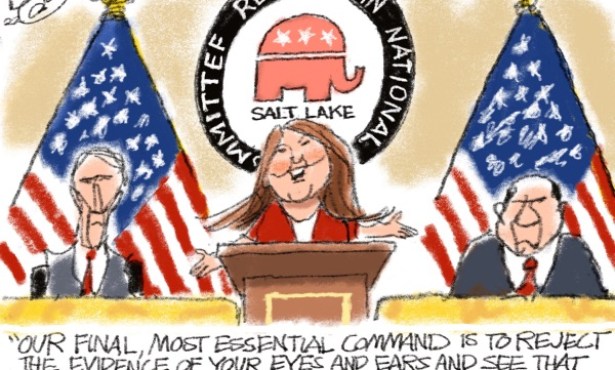

Cox, Faulconer, Elder et al. have essentially framed this issue as one of mental illness requiring forced removals of the homeless from our streets into mental institutional settings. Their mental-health talking point is best summed up by John Cox: “[W]e’re going to have to force people into that treatment if need be.” (Ironically, it was the repeal of funding by governor Ronald Reagan’s administration for federal community health centers that created an explosion of people, including the mentally impaired, living on California streets.)

It would be a mistake to conclude that homelessness is predominately a mental-health issue. Clearly, living on the streets can exacerbate mental-health conditions. However, researchers like the California Policy Lab have found that while “[homeless] people who are suffering from substance use disorder or mental illness are very visible [and] challenging, there is a very large unsheltered population that doesn’t have either.” Homelessness, like all complicated problems, is multi-dimensional. Its causes include poverty, tragedy, abuse, family deaths, and physical disabilities, as well as mental health and addiction.

If you’re interested in California government addressing this issue you should vote not to recall Governor Newsom. On July 19 he signed a comprehensive and historic housing and homelessness funding package as part of his $100 billion California Comeback Plan. The legislation invests $12 billion over two years to tackle homelessness. This is the largest investment addressing the homeless problem in state history. It focuses on behavioral health, housing and solutions to tent encampments. It allocates $5.8 billion to add 42,000 new housing units for the homeless; $3 billion to house those with the most acute behavioral and physical needs, $3.9 billion for mental health, and $2 billion for local governments to address problems like tent cities. There are no line items for punitive actions against homeless people.

It seems to me that the seminal issue in addressing homelessness is their occupation of the “commons,” like the tent encampment on Venice Beach.

Cities have always had common places, with commercial and recreational facilities where people congregate. Historically, such common places developed norms of behavior allowing different kinds of people to mingle. Learning how to resolve life in the commons has been left out of the homeless recall debate. Venice Beach is a “commons” where people from all over Los Angeles go to swim, recreate, and sunbathe. It is not, nor should it be, a place for a tent encampment of homeless people living at the beach.

Historically, when norms in the “commons” were violated, the etiquette was restored by law enforcement. This doesn’t necessarily have to change, as long as the police officers removing the encampments are trained to deal with homeless populations, and Restorative Courts, not traditional law courts, are used to deal with recalcitrant problems.

Restorative Courts counsel homeless people and refer them to housing, and /or treatment facilities when needed, rather than fine or imprison them for violating local laws. Community police are trained to understand the diverse nature and needs of homeless populations. Newsom’s bill provides sufficient funding for local communities to establish both of these kinds of innovations, along with resolving encampment issues like the one at Venice Beach.

If we keep Governor Newsom in office all of this can happen.