Full Belly Files | Can Old Vines Get Official?

This edition of Full Belly Files was originally emailed to subscribers on June 30, 2023. To receive Matt Kettmann’s food newsletter in your inbox each Friday, sign up at independent.com/newsletters.

In an industry that’s awash in romantic notions of beautiful places, interesting personalities, and authentic connections to the past, few ideas pull on the wine world’s heartstrings more strongly than the allure of old vines, those gnarled plants that continue to produce quality wines many decades, and even many generations, after first taking root.

I’ve been fascinated with old vines since the earliest days of my wine writing career, when I started to appreciate how directly they link today to yesterday, While carrying familiar flavors and textures through the vintages, the vines serve as repositories for tales about each vineyard and the people who’ve cared for it over the years, which is simply storytelling gold as both a journalist and interested consumer. I’ve written stories and spoken on podcasts directly about old vines (see: here, here, here, here, and here), and the topic is frequently woven into my other features as well (like here, here, and here).

As I’ve researched and reported on old vines throughout the years, I’ve run into a number of minor debates and curious questions around the topic. The age of many vineyards really depends on who you talk to and which story you believe. Without proper documentation, which can be spotty the further you go back, you wind up relying on anecdotal information, or historical photographs, or other auxiliary evidence that can sometimes be pieced together to reach a likely origin date.

There’s also the question of what makes a vine “old.” Should we only celebrate vines that are more than a century old, or should we move that meter back closer to the present?

And last but not least, is there a true value to these old vines? Did they survive because they were especially good vines to begin with, or are they actually better because they’re old? Do they make better wines? If so, why?

There are a number of old-vines-minded organizations that exist, including California’s Historic Vineyard Society, whose website is worth a rabbit-hole dive for anyone interested in the state’s viticultural past. There are also efforts in places like Australia, Chile, and South Africa, where the Old Vine Project is certifying heritage vineyards and even adorning bottles with special labels.

But, as announced during a webinar this past Monday, there’s now a global umbrella organization for registering and recognizing old vines. A project spearheaded by the Old Vine Conference, the Old Vine Registry is now live at OldVineRegistry.org, so far listing 2,200 vineyards from 29 different countries. (Their answer to what qualifies as “old” is 35 years, the time that most vineyards will be replanted if not performing well.) And the list will grow, as there are at least a few vineyards I recently visited in San Benito County that aren’t yet on the list (Wirz and Gimelli, to name two), and I’m sure there are many more like that.

The nonprofit, volunteer, totally grassroots effort is being led by a team of wine industry superstars, namely renowned wine critic Jancis Robinson, who started a list of old vines in 2010 and then wrote a 2013 article about Rosa Kruger’s South Africa old-vine project that further set things in motion; Master of Wine Sarah Abbott, who rallied the industry around the idea; and Robinson’s editors Tamlyn Currin and Alder Yarrow, who compiled and designed the registry. (I interviewed Alder about his book in 2015, and he was kind enough to show my own book some love in 2021.) They all spoke during Monday’s webinar, which you can view for yourself here.

So far, Santa Barbara County has seven entries on the registry, with Gypsy Canyon’s mission grape wines being the oldest, planted in 1887. Both Cambria (1971) and Sanford & Benedict (1971 and ’72) are split into two entries for their chardonnay and pinot noir plantings. Ernest Wickenden, which is used by Foxen Winery, dates back to 1966, while Julia’s Vineyard — owned by Jackson Family Wines, like the Cambria sites — was planted in 1970.

The Old Vine Registry goals are pretty modest for now: Grow the database into a one-stop shop for accurate info on these vines; use the platform as a tool toward preserving these vines; and fundraise as much as possible to pay for the digital and design costs.

But like is being done in South Africa, I’m sure many producers and consumers would welcome a special label for these old vine wines. The regulatory hurdles for doing so are surely more daunting and bureaucratic than we can imagine, but at least we can hope.

Lunch @ Duvarita + Christy & Wise

As I write this on Wednesday afternoon, I just returned from a lunch at Duvarita Vineyard near Lompoc, which is located just west of the Sta. Rita Hills boundary. Vineyard owner Brook Williams, who bought the former Presidio Vineyard property in 2012 and now makes the J. Dirt Wines, invited me to join many of the producers who buy fruit from that vineyard as well as Christy & Wise, another property he planted on the sandy hills just to the east. The last time I’d come to such a gathering was in 2020, and that experience became the introduction to my book Vines & Vision: The Winemakers of Santa Barbara County.

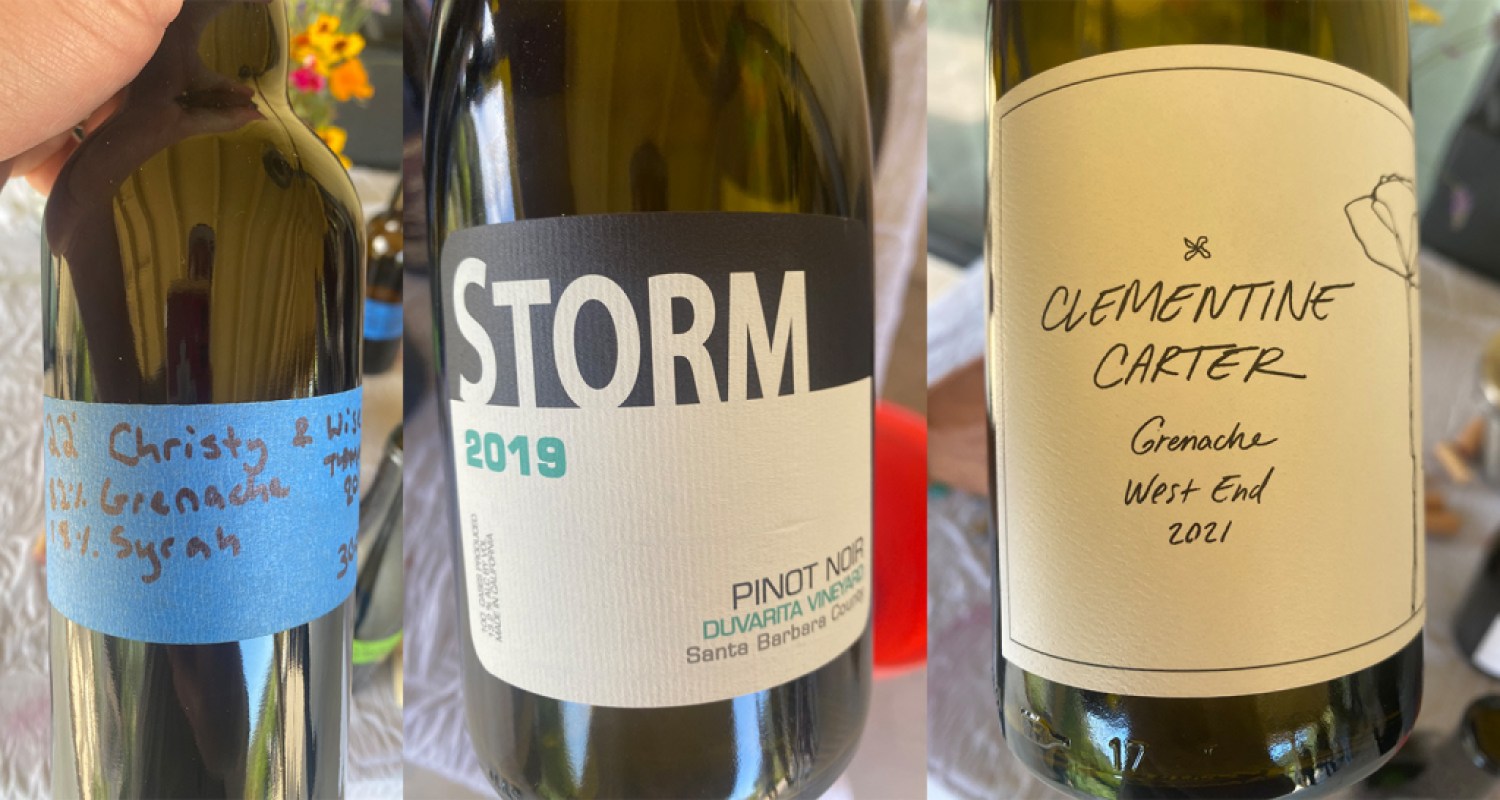

This time around, there were actual wines to taste from Christy & Wise as well as examples from Duvarita, both of which are wind-tormented properties that struggle to put out much of a reliable crop. And yet the grapes that do get harvested are coveted by wineries both veteran, such as The Ojai Vineyard and Lindquist Family Wines, and on the slightly younger side of the scale, such as Storm, Dragonette, and Camins 2 Dreams.

The pinot noirs that we tasted from Duvarita tended toward the earthy, savory, umami-laden range of the flavor spectrum. “They taste like whole-cluster without being whole-cluster,” said Brandon Sparks-Gillis of Dragonette of the herbal qualities as we sipped on one from a new brand called, punningly, Cote of Paint. Sonja Magdevski of Clementine Carter explained, “There’s an interesting kinship to all of these pinots,” to which Williams agreed: “They’re all from the same home, but they went to different colleges.”

The wines from Christy & Wise were interesting in their own right. The entire vineyard is head-trained rather than on a trellis system, including the chardonnay, which is quite uncommon for that variety. The grenaches were especially unique, showing both elegant floral qualities as well as fairly intense tannins.

The head-trained pinot from Christy & Wise is struggling the most, due most likely to the endless wind but also the gophers. But that wind is only expected to increase as climate change warms up the inland areas, sucking more air that way. “This is why we have more syrah, mourvèdre, and grenache,” said Williams. “They’re wind-averse, or at least wind-tolerant.”

From Our Table:

In case you missed them, here are some recently published stories:

- Leslie Dinaberg checked in with Sushi by Scratch: Montecito for this report.

- I interviewed Eleven Madison Park’s Chef Daniel Humm via email in advance of his dinners at Caruso’s this weekend.

- Vanessa Vin checked in with SAMsARA Wines for a tasting of the 2013 vintage, which is on sale now.

- I texted about Lee “Scratch” Perry with Jack Johnson to write this short piece on his new dub remix album.

You must be logged in to post a comment.