Remembering Old Valley Days with Howard Sahm, Los Olivos Dairy Farmer

Longtime Farmer Shared Oral History of Valley Life with Students

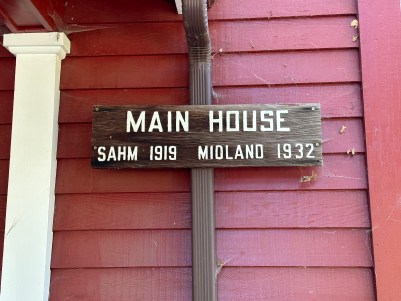

On a bright fall day more than 20 years ago, Howard Sahm and his wife, Ruth, welcomed my oral history students and me to their 19th-century house tucked away on a back street in Los Olivos. Mr. Sahm, who died in 2011 at the age of 85, had lived his entire life in this very house, built by his grandfather. “This was all our dairy property,” he said, encircling widely with a gesture of his arms. “It was run by my father and me until 1964.”

He had known Los Olivos in a very different era. He shared boyhood memories of playing marbles on the corner, making newspaper kites, and delivering papers on his bicycle for a penny a paper. “I’d go five and a half miles every day, out to the stores, by the schools, up Figueroa Mountain Road…,” he recalled. “It was gravel roads until the1930s, when they put down the blacktop. In later years, if we wanted to go to a movie on a Saturday afternoon, we’d ride our bikes into Solvang. There was a theater there where the Bit O’ Denmark is, and there was a bowling alley next door.

“Later, when I got to driving, after I became 16, there’d be a Saturday-night dance every week, old-time dances here at the grammar school or Santa Ynez, and then the regular dances down in the Veterans Hall in Solvang. We had live music, not albums. Our band instructor was Bob MacDonald, and the principal, Hal Hamm, he played the clarinet, and then there was Ivan and Ellen Sorenson — he played the fiddle and bass fiddle, and Ellen played the piano. For the dances up here, it was banjo, fiddle, piano … square dancing. We danced with everybody — two-step, foxtrot, polka. Girls asked boys, too. We liked ‘Melancholy Baby,’ ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz,’ ‘Let Me Call You Sweetheart,’ … songs like that. Ruth and I used to dance, and we never missed a polka, but then I had the stroke a few years ago, and my right foot wouldn’t quite track. And now I wouldn’t have air enough to polka.”

One of the students asked him about life during the Depression. “Everybody was in the same boat,” he said. “Nobody had any money. There was a hobo camp up by the bridge at Mattei’s. They’d come here and ask my mother for a potato, and I don’t think anyone ever got turned away. She’d say, ‘Okay, if you wanna chop some wood.’ They’d chop up a half a dozen pieces of wood, and she’d give ’em a potato, or whatever. But she wouldn’t give it to them just for nothing. They had to earn it. The work gave them dignity.”

He mused, “I wish I had a video of some of the characters we used to have here in Los Olivos. There was a big bench outside the post office, and they called that the ‘spit ’n’ argue club.’ Those guys would come there in the morning, waitin’ for the mailman, sittin’ on the bench, and they’d tell stories: the biggest fish, or the biggest spread of horns on the deer. One fellow who lived up there, Frank Cooper, was a staunch Democrat, and there was another guy who would argue Republican, and they’d be struttin’ around, chest forward, rooster-style, arguing….”

Operating the dairy farm demanded more and more of Howard’s focus over the years, and it was hard work. “We were milking 130, 135 cows,” he said. “We furnished milk to Camp Cooke, and we furnished milk to the creamery in Santa Barbara, and they in turn furnished it to marine bases, hospitals…. We had registered Guernseys, and in later years, we put in some Holsteins with them for a little more volume, less butter fat. They were all different, and we knew each cow, and all of ’em had names: Bossy, Opal, Suzy, Fanny, Petunia…. We had one that always had twins every year. It was easy to tell ’em apart. Even the Angus — black as shoe leather, but every one of ’em was different.”

He continued, “Before we sold out, our contract was big enough for one man, but it wasn’t hardly big enough for two, yet it took two to operate. Then they closed the plant down in Santa Barbara and started shipping our milk to Los Angeles. That increase in the freight, and the contract and all that, was just economically hard for us. At one time, there used to be 12 or 14 dairies right here in the valley, and about 55 or 60 in Santa Maria. Now there’s just one here in the Valley — Jacobsen’s out on Baseline Avenue — and one in Santa Maria.”

He continued, “So, in the late ’50s, early ’60s, it was time to think about selling. One of the dairy men over in Buellton bought our cows. And it wasn’t easy. You know, you’re born and raised with something.… Back when we was operating, my mother had to cull a cow sometimes. It didn’t bother her; you’d come back, and there’d always be one to take the place. But oh, that last day. The last day, it was … it wasn’t easy.”

All these decades later, Howard Sahm had tears in his eyes remembering. “Nothing was easy,” he told us. “But my dad always had a philosophy — never ask a hired man to do something that you wouldn’t do. You work hard. And that stands true. You just work hard.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.