Santa Barbara Unified Staff Seeing Pink

School District Community Raises Concerns over Looming Cuts to Positions, Hours

Pink slips — or layoff notices — are a routine process for school districts. Usually, new teachers and other school staff receive them annually until they have established some seniority.

But this year, stacks almost an inch thick sit on some principals’ desks. They have piled up in school districts across the state, including Santa Barbara Unified, mainly due to COVID-19 hires and the loss of one-time, pandemic-era funding.

Employees are bearing the burden of uncertainty with these notices and are, frankly, angry, frustrated, and freaking out. Many staff members on the chopping block are considered low-income based on Santa Barbara housing costs. They quickly questioned: Why are the people making the least shouldering the most of the strain?

The district is mostly gutting classified positions — such as campus safety and office assistants — and newer positions paid for by one-time funds. The March 12 school board meeting, where boardmembers approved the layoff notices, was wrought with worried staff.

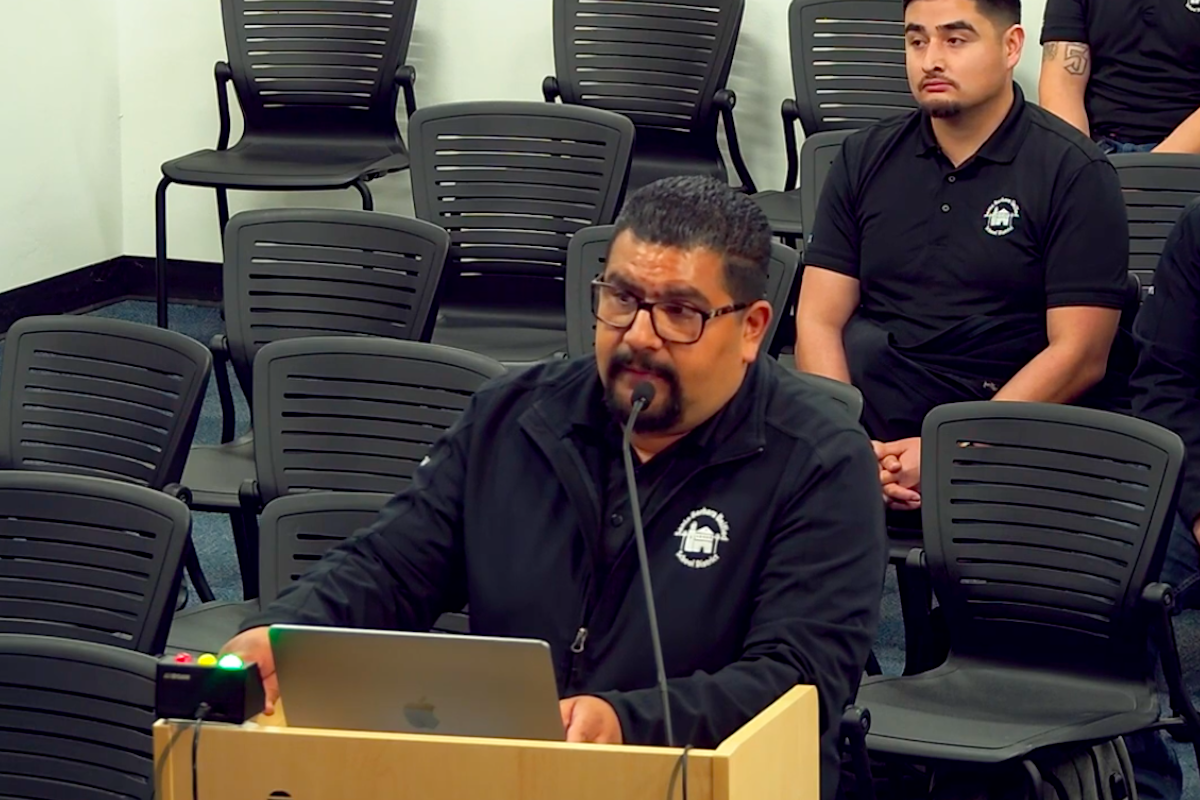

“I am a first-generation immigrant and dreamer,” said Ed Herrera, an IT support specialist with the district.

He explained that he grew up in town, attended local schools, and is now raising his family here — he even married his high school sweetheart. He choked up as he spoke to the board, as his position is one of roughly 90 up for elimination.

“My goal at the district was to find stability that wasn’t offered anywhere else,” he said, explaining that he worked as a custodian for his first two years.

“And it wasn’t until I had the chance to come to [Educational Technology Services] where I felt like I could truly grow and make a difference in the education of these young students. Most of them look like me and see careers in the field of tech. It is devastating to me that I may lose my job to provide the basic necessities for my family and uproot them from a place they were born and raised.”

It is a difficult position to be in, district leadership has said. Although it is usually standard procedure, they have not given out pink slips in three or four years, since pre-pandemic.

They said they do not want to lay off employees, but a “perfect storm” of external factors — including a new law saying they had to give out notices by March 15, whereas in the past they could do it with a 60-day notice — is forcing their hand, causing over-notices (more employees will receive a notice than actually be laid off). The bumping process — where promoted employees are “bumped” down to a former position — also complicates matters, they said.

Credit: Paul Wellman File Photo

“It is definitely more than a usual year — way, way more than normal,” said Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources John Becchio, a former principal of Santa Barbara High School. Becchio, the stock image of a friendly, Santa Barbara–born educator, is the only remaining cabinet member of the former administration after Superintendent Hilda Maldonado was hired in 2020.

“There’s a higher stress level about it for employees, too. When I was principal, and we did these every year, it was the same people every year. I’d call them in, like, ‘Oh, yep, same notice.’ This year is different because, for these people, it’s not an annual thing they’ve experienced.”

Becchio explained that when he began as a teacher at Santa Barbara Junior High, he received a notice every year for about the first four years. “Every year, I didn’t know whether I had a job,” he shared. However, teachers are not the ones receiving pink slips this year, since the union and the district agreed to keep class sizes small. Hiring and retaining extra teachers for smaller class sizes was originally a one-time-funds expense, but the $6.2 million cost will need to be shifted into the regular budget.

If they had not come to that agreement, somewhere around 50 teachers would have also received a layoff notice this year, explained Kim Hernandez, assistant superintendent of business services.

“We need to prepare for getting ourselves back to a place where we don’t have those ongoing expenditures that we were paying for through the use of the one-time funds,” Becchio said.

Some staff have accused the district of using the layoff notices as a “scare tactic” to undermine support for the unions as contract negotiations with both teachers and classified employees continue. Becchio called that an “unfortunate statement,” noting converging factors of an expected state budget crisis and declining enrollment — the district is community-funded but receives some funds from the state to support programs such as special education — as well as a lack of certainty around upcoming revenues and expenditures. He said the labor contract proposals as of now are adding up to $42 million in new expenditures.

“To suggest that it’s to scare people … there’s just nothing behind that,” Becchio said. “These are our people; these are our employees who we care about. So to play games with their livelihood would just be, I mean, not something that we would engage in.”

Another question that has been raised is: What if the people at the top took pay cuts? Yes, there are management positions that were pink-slipped — including the director of community partnerships and director of educational technology services — but it is the lowest-paid employees who are taking the brunt.

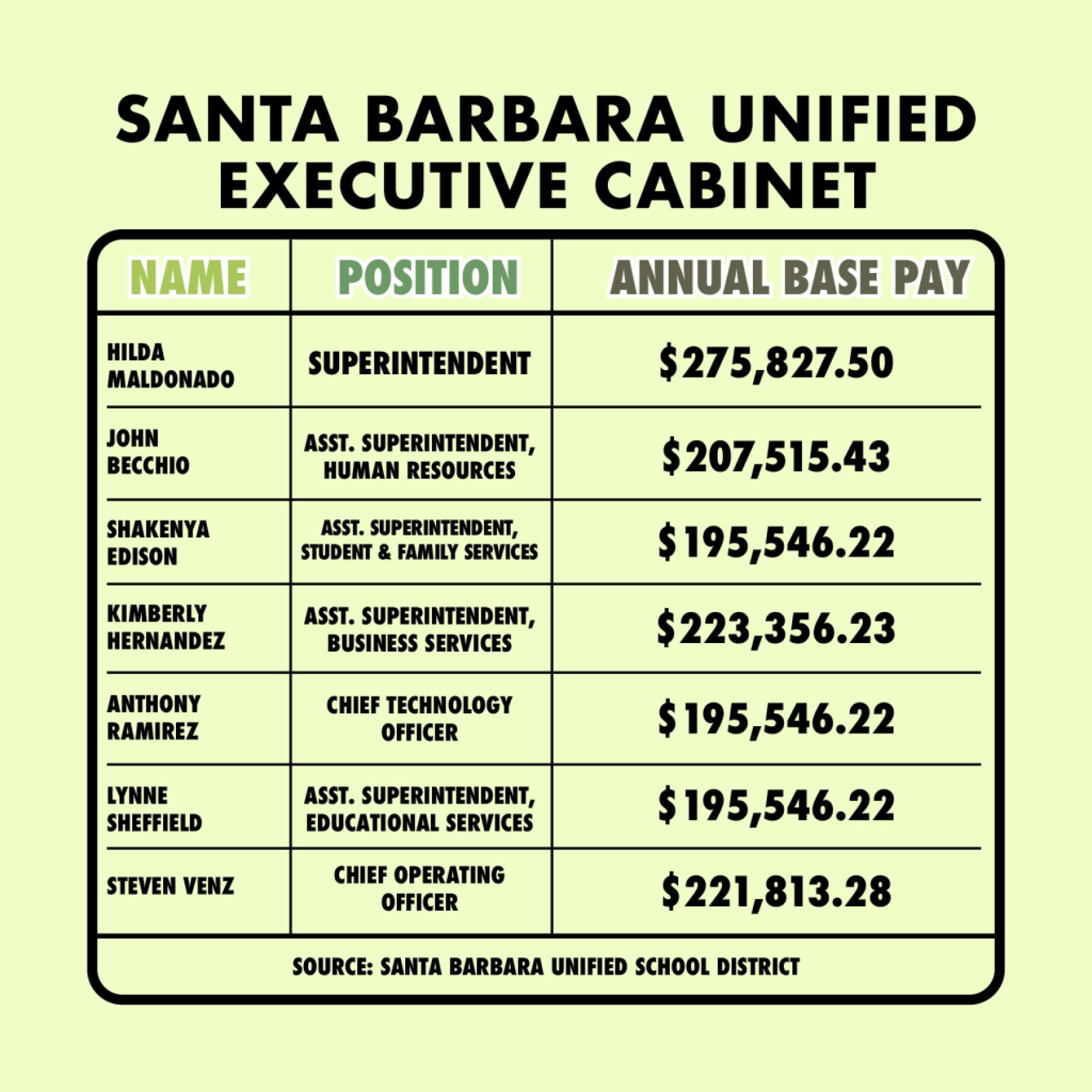

The annual payroll for Superintendent Maldonado and the district’s six other executive cabinet members costs the district a little more than $1.5 million a year. They all make $195,000 to $275,00 per year in base salary. The grapevine has also pointed out that Steve Venz, a former colleague of Maldonado’s from Los Angeles Unified who took on the newly created role of chief operating officer and is making $221,813 in salary, was technically a COVID hire. But no one at the top is seeing pink.

In consideration of this common critique, the Indy did the math. If each cabinet member took a 10 percent pay cut, the district would save a little more than $151,500 per year, which is roughly equal to the annual salaries of three mid-salary-range campus safety assistants, who, alongside bilingual paraeducators, are facing the highest number of reductions.

At Santa Barbara High School, for example, all campus safety assistants received notices that they may have either their positions cut or their hours reduced. One campus safety assistant who wished to remain anonymous said he has worked in the district for years and was “in shock” to hear that his hours would be reduced.

When the district did its survey on who was considered a “trusted adult” on campus, many students mentioned campus safety assistants, he added. They help students “get on their feet” and get to class, walk them to the counselor’s office, and even offer an ear to those who are going through hard times. However, he said that a lot of them are now looking for new jobs since they need full-time work.

“We’re adults trying to live in Santa Barbara just like everybody else,” he said.

“I tell the students I might not be coming back next year, and they’re like, ‘What do you mean?’” he continued. “We have direct contact with them. It doesn’t make sense they’re reducing our hours.… Top district staff make three times as much as us, and they don’t have this kind of direct contact with the kids.”

Although admittedly few and far between, top staff have taken (usually modest) pay cuts during hard times in other California school districts. For example, in 2018 in the Byron Union School District, Superintendent Debbie Gold voluntarily rolled back her salary by 5 percent, stating she was “committed to making other substantial cuts to administration” when the district was facing financial struggles. And in 2022, the Orange County Board of Education voted 4-1 to cut Superintendent Al Mijares’s annual salary by 13.7 percent.

When asked if they considered taking a salary cut, Becchio and Hernandez said the district has to be competitive with other school districts. Running a unified school district with a $200 million budget and thousands of employees is not easy and requires “the best” people in administrative positions, they said, especially with big, ongoing initiatives such as the new literacy curriculum adoption and their work combating anti-Blackness.

Around six years ago, Becchio estimated, the board did vote to decrease the salary schedule for cabinet members. However, now, he said that would not “add up to paying for a lot because there’s just not a lot of us…. So while it is a drum we hear beating, it just does not move the needle too much on our budget.”

It is important to remember that the pink slips are precautionary notices, the district emphasized. Final notices will go out in May. Meanwhile, questions and concerns around the district’s priorities continue to swirl around the community, as the fate of staff members hangs in the balance.

Premier Events

Sun, Apr 28

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Sat, Apr 27

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

Sat, Apr 27

3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

Sat, Apr 27

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03

8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04

10:00 AM

Solvang

Touch A Truck

Sun, Apr 28 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

AHA! Presents: Sing It Out!

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Things with Wings at Art & Soul

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Lompoc

RocketTown Comic Con 2024

Sat, Apr 27 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Plant Fest

Sat, Apr 27 3:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Trapeze Co and Unity Shoppe Spring Food Drive

Sat, Apr 27 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Beau James Wilding Band Live

Sun, Apr 28 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Earth Day Festival 2024

Wed, May 01 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

American Theatre Guild Presents “Come From Away”

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

100th Birthday Tribute for James Galanos

Thu, May 02 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Meet the Creator of The Caregiver Oracle Deck

Fri, May 03 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Fair+Expo “Double Thrill Double Fun”

Fri, May 03 8:00 PM

Santa barbara

Performance by Marca MP

Sat, May 04 10:00 AM

Solvang

You must be logged in to post a comment.