Book Review | ‘The Manicurist’s Daughter: A Memoir’ by Susan Lieu

An Immigrant Story Is Just One Strand of This Satisfying Read

Several years after the fall of Saigon, Susan Lieu’s parents fled Vietnam to escape suffocating Communist rule. Leaving was an enormous risk filled with uncertainty, a blind leap into the unknown. The overcrowded boat bound for Malaysia might flounder in a storm or be commandeered by Thai pirates. If the boat’s engine failed, the passengers might perish of starvation or dehydration. That the Lieu family made it to Malaysia, then Indonesia, then Singapore, and finally to America after being granted asylum status was as much a matter of luck as grim determination.

The Manicurist’s Daughter is in one sense a quintessential immigrant story of pluck, family, and striving. After the Lieus landed in the San Francisco Bay, the family’s fortunes were driven by Susan’s mother, known as Ma, a human dynamo. Ma opened a nail salon in the East Bay and used this enterprise to sponsor her siblings and other relatives; at one point, the extended family numbered 13. Everybody worked in the salon, seven days a week, with very few days off each year. Before long, the family purchased a home and opened a second salon. Susan’s older brother went to Stanford while Susan graduated from Harvard. Had the story ended there, it would be remarkable.

But the immigrant success story is only one strand in this rich memoir.

As a young person in war-ravaged Vietnam, the thought of eating meat every day of the week was something Ma dreamed about, abundant food being a measure of wealth and security. For the Lieu clan, preparing and eating food was an essential ritual, more than a means of sustaining laboring bodies; it was how they preserved their extended familial bonds and cultural identity. Many of Susan’s recollections of her mother are associated with meals, favorite dishes, and particular smells and textures; the memoir contains dozens of references to food.

But food also became Susan’s nemesis. In her early days at Harvard, she was lonely and isolated and ate for comfort, gaining unwanted pounds she knew would expose her to ridicule when she saw her family again. Susan internalized the verbal arrows and put-downs from her father, siblings, and grandmother; her blood relatives were more judgmental than complete strangers.

In one poignant example of this dynamic, Susan recalls the day she told her father, Ba, of her acceptance to Harvard. Expecting Ba to be thrilled, she is instead crushed when he asks her why she didn’t get into Stanford.

At the age of 36, Ma decided to do something for herself: a bit of cosmetic surgery, sculpting around the nose along with a tummy tuck. Ma scheduled the procedure with a surgeon who advertised in Vietnamese newspapers. Unbeknownst to Ma or her family, this surgeon carried no malpractice insurance and was practicing under a cloud of formal complaints and inquiries. What was supposed to be a routine procedure took a wrong turn, and Ma wound up in a coma with no chance of coming out of it; her eldest son — a teenager at the time — made the decision to end life support. Susan was 11 years old. Ba was 42 and suddenly responsible for four children and a business he wasn’t equipped to manage.

While the memoir is primarily centered on Susan’s determined search for her mother, it’s also an investigation into why Ma sought plastic surgery in the first place, and the many ways her death affected the Lieu family. But Susan is the only person willing to talk about what happened to Ma, to probe and process her death from as many angles as possible, and this realization reinforces her feeling of being the hysterical youngest child. Her brothers and sister follow Ba’s example, which is to change the subject or retreat into silence. Why bring up what can’t be changed? Susan describes reading through deposition transcripts, seeking details her father and older siblings forgot or didn’t speak about. Driven to leave no avenue unexamined, she even consults a medium.

While Susan is searching for information about her mother, she’s also trying to find her place in the business world, torn between family expectations of career success and her own artistic aspirations. In the process of creating her one-woman theatrical show titled 140 LBS, Susan comes to understand how differently each person within a family can experience grief. Her siblings, aunts, and Ba didn’t suffer any less; quiet suffering is still painful and traumatic.

Lieu is brave and vulnerable, willing to expose her deepest feelings and fears, and some embarrassing missteps. Like every human story, this one contains numerous layers. As the layers in The Manicurist’s Daughter are peeled back, a remarkable mother and her equally remarkable daughter are revealed.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Premier Events

Sat, Jun 01

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Free Tango Community Class with Gustavo Russo

Wed, May 29

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

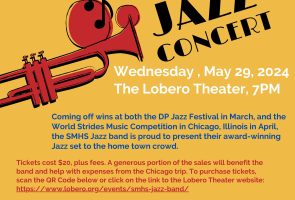

One Night Only San Marcos H.S. Jazz

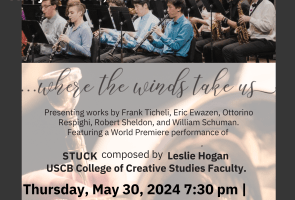

Thu, May 30

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Ensemble Theatre Presents “Alice: Formerly of Wonderland”

Thu, May 30

7:30 PM

Isla Vista

UCSB Wind Ensemble Spring Concert

Fri, May 31

9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

FILM Screening: “Point Break”

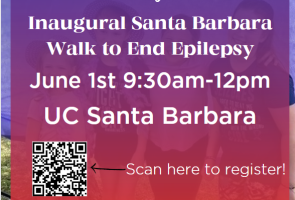

Sat, Jun 01

9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Inaugural Walk to End Epilepsy Santa Barbara

Sat, Jun 01

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

S.B. Zoo Brew

Sat, Jun 01

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

State Street Ballet Academy Presents: Tina the Ballerina

Sun, Jun 02

4:00 PM

Ojai

Ojai Wild!

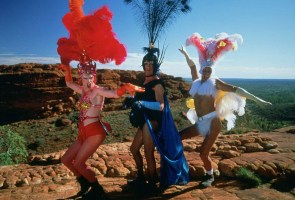

Fri, Jun 14

9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

FILM Screening: “The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert”

Sat, Jun 01 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Free Tango Community Class with Gustavo Russo

Wed, May 29 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

One Night Only San Marcos H.S. Jazz

Thu, May 30 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Ensemble Theatre Presents “Alice: Formerly of Wonderland”

Thu, May 30 7:30 PM

Isla Vista

UCSB Wind Ensemble Spring Concert

Fri, May 31 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

FILM Screening: “Point Break”

Sat, Jun 01 9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Inaugural Walk to End Epilepsy Santa Barbara

Sat, Jun 01 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

S.B. Zoo Brew

Sat, Jun 01 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

State Street Ballet Academy Presents: Tina the Ballerina

Sun, Jun 02 4:00 PM

Ojai

Ojai Wild!

Fri, Jun 14 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara