On the face of things, the subject matter encountered in Duncan Simcoe’s current Night Visions exhibition at Westmont’s Ridley-Tree Museum of Art is seemingly commonplace. He presents scenes from the suburbia he knew growing up in Orange County, deals with implements of travel as iconography — which he calls “means of conveyance” — observations on a famous plane crash and racist violence, and a loosely spun dalliance with rock & roll.

But behind and around these commonplace realms and objects, mysteries and questions lurk. Not for nothing is one strong series in the show dubbed “Mythinburbia.” Mysticism visits the ‘burbs: There goes the neighborhood.

The artist’s unique means — painting/drawing on tar paper — and artistic messaging grow ever-denser on closer scrutiny. Scrutiny and contemplation are necessary tools for the job of appreciating Simcoe’s art.

With intriguing degrees of subtlety and inference, Simcoe’s art satisfies the underlying but not dogmatic adherence to spiritual themes at the Christian-based Westmont College. Simcoe, who follows the Eastern Orthodox path and teaches at the California Baptist University in Riverside, California, inquisitively broaches the secret life and spiritual questing bubbling under the surfaces and conventions of contemporary life.

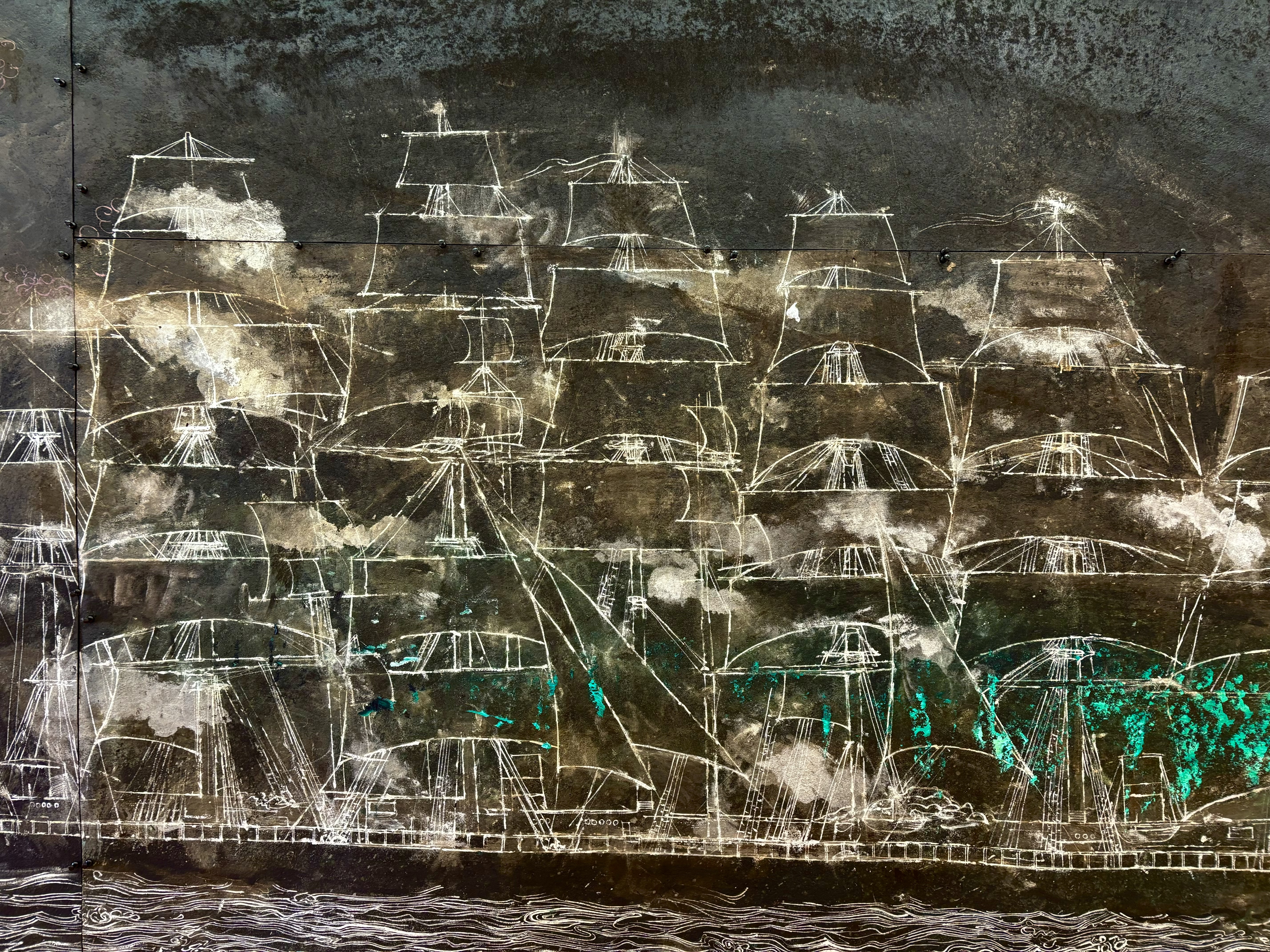

The very exhibition title Night Visions (curated by Gordon Fuglie) serves a dual purpose, descriptive of the visual and spiritual nocturnes involved and, via his tar paper base, the inverted art logic of light on dark. In some way, the effect reminds us of black velvet paintings, although with a very different cultural context. While Simcoe’s art suggests the linear quality of drawing, a skill he masters, it is actually created with oil paint and flecked with loamy tones to enrich and also further mystify the end result.

In the museum’s entrance gallery, we’re introduced to his “means of conveyance” interest (conveyance implying both actual travel and philosophical search modes) with the vast “Means of Conveyance (Sailing Ship)” painting, suggesting a ghostly vessel which slipped out of a dream. Across the room, Simcoe tangentially taps into the post–George Floyd era of awareness of racial violence not by directly addressing Floyd’s murder but by interpreting a news story photo of a violent protest in the Dominican Republic in the 1950s. The trans-historical vantage lends a deeper recognition of the dark, seemingly unstoppable legacy of racial violence through human history.

In a related way, Simcoe finds new artistic angles to respectfully contend with the harsh historical reality of the tragic Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 crash in 2014, which killed all 239 passengers. “Black Box” is a set of integrated elements — a triangular form conveying an ocean and a plummeting toy airplane, Persian rug-like stacks of tar paper marked with religious iconography across religious faiths — forming a distinctive and open-ended memorial through art.

The “Candelabra” series shifts orientation and format as tall pieces based on an inverted triangle structure. The realistic imagery at the base, whether a swimming, swooning couple or a film noir–tinged smoking man, gives way to a mysterious emanation of huge ectoplasmic plumes consuming most of the pictorial space.

A centerpiece of the main gallery, and the show itself, is his powerful Mythinburbia series, in which flinty linear drawings of cookie-cutter tract houses take on the feel of architectural drawings irradiated by some cosmic force — and as if seen through “night vision” goggles. “#17 (Fire Starter)” blends a generic ranch house and an apparitional/memento inset image of the artist’s late wife (who died of cancer in her 50s), with wall text quoting the sage Bruce Springsteen: “you can’t start a fire without a spark.”

In “Mythinburbia #19 (Vice),” the familiar grid of humble homes is flanked on its edges by images of a man and woman in a face-off, with a central talismanic image of a large vice floating above the house, signifying inter-gender tension and fixity.

Lest we buy into the idea of the suburbs as Simcoe’s singular or most concentrated point of fixation, Night Visions also leads us into other realms, often reflective of his spiritual nature at the core. His religious — and specifically Eastern Orthodox — perspective comes through clearly in a dark-lit alcove of the museum, in “A Distant Mirror: A Meditation on St. Catherine.” He pays tribute to the saint, martyred in 305 C.E., with a plastic skeleton, and his own paintings thereof.

In another surprising turn, his “Rock and Roll” is a large, slowly revolving cylinder bearing images of antique cruciform church designs. The odd, soothing piece might function as a summarizing statement of the artist’s intent, with its meshed different shades of icon worship and ritual, where the sacred and the secular meet in surprising and potentially illuminating ways.

Duncan Simcoe’s Night Visions is on view at Westmont’s Ridley-Tree Museum of Art through November 9. See westmont.edu/museum.

Premier Events

Fri, May 02 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

The Rhythm Industrial Complex: Live at Carr Winery

Sat, May 03 9:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Tenants Union Assembly!

Sun, May 11 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mother’s Day Brunch at Hilton Santa Barbara

Sat, Jul 26 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Pink Floyd Laser Spectacular LIVE present SHINE ON

Sat, May 03 9:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Tenants Union Assembly!

Sat, May 03 9:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Fun in the Sun Walk & Roll for Inclusion

Sat, May 03 10:00 AM

Santa Ynez

Annual Chumash Earth Day

Sat, May 03 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Revels Celebrates May Day!

Sat, May 03 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Blessing of the Bicycles & Blessings Ride

Sat, May 03 3:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Santa Barbara Music Club Free Concert Saturday

Sun, May 04 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Astro Fest

Sun, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara, CA 93105

Santa Barbara Fair & Expo

Sun, May 04 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Treble Clef Chorus Sing Out for Spring!

Sun, May 04 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.