Maybe the toughest gig in Santa Barbara County is health care in the county jail. Every few months or so, the county supervisors square off with Sheriff Bill Brown over just this — jail deaths, medical quality control issues, and whether the county’s getting its money’s worth from Wellpath, the private company that’s paid $17 million a year to take care of inmates in the county’s two jails and juvenile detention facility. The county supervisors, increasingly frustrated, recently put the jail contract — which expires at the end of next March — out to bid. And just this week, the parent company of Wellpath — which provides health care services for county jails in 34 of the state’s 58 counties — filed for bankruptcy in a Texas court.

According to company press releases, Wellpath — the biggest private correctional health care provider in the nation — is looking to re-organize more efficiently, not go out of business. The company promises a seamless transition for however long it takes for its Chapter 11 bankruptcy case to wend its way through the legal system.

But in county government circles — where the politics and economics of crime and punishment command a vast portion of the supervisors’ collective cranial capacity — the news qualified as a great, big wait-and-see WTF.

“We’re all on the edge of our seats waiting to see how this plays out,” stated Tanja Heitman, the county’s onetime and longtime probation chief recently hired to bird-dog criminal justice reform for the county administrator’s office.

Kip Hallman, a co-chair of the Wellpath board of directors out of Tennessee, clarified that absolutely nothing is going to happen to any of the 34 county jails served by Wellpath in California. In California, he stressed, facilities operated under the Wellpath name are, in fact, owned by a wholly separate entity, California Forensic Medical Group (CFMG), which he said is owned primarily by the group doctors. CFMG, in turn, contracts for certain management services from Wellpath. But the two entities, he stressed, have no ownership overlap.

But, Hallman added, Wellpath — the real one, not CFMG — filed for bankruptcy because of the massive hit it sustained during COVID. “COVID was very challenging for everyone in healthcare, but especially so for people providing the sort of services we do.”

Heitman suggested that the cost of litigation might be driving the decision as well. Everywhere one looks, she noted, Wellpath is getting sued for medical malpractice by inmates and their families.

It’s not the only provider getting sued, but as the biggest, the company generates the lion’s share of litigation and media notice. As what goes on behind bars has come under greater scrutiny by civil rights activists and mental health advocates, such lawsuits — and likewise the awards imposed by juries — have been piling up.

Hallman declined to reply to that line of speculation, stating he preferred to stick to subjects discussed in the company’s press release.

The most recent skirmish over the jail involved what the supervisors contended was lax contract management and oversight by Sheriff Brown and his commanders over Wellpath’s contract. The company failed to meet the medical staffing levels required by the contract but got paid in full. By how much exactly, the numbers vary. But most estimates hover around $500,000.

At supervisors meetings, Brown has stood up for Wellpath with the ardent loyalty of a foxhole buddy. It’s easy to see why. Together, Brown and Wellpath have weathered the nightmare of COVID and the inevitable logistical challenges involved in opening up the new Northern Branch Jail. And even under the best of circumstances, running a medical and psychiatric ER in a county jail setting 24/7 is flat-out hard.

The supervisors want Brown to make sure they get their money’s worth and that inmates get the care they need. But as sheriff, it’s Brown’s jail to run as he sees fit under state law. And he’s made it clear he won’t tolerate any encroachment on his jurisdictional domain.

The two sides, however, hammered out a deal a few months back. The County Public Health Department would hire a full-time nurse and part-time doctor — newly created positions — who would be assigned to monitor the medical charts of county jail inmates to make sure they’re getting the care they need. In addition, they would suggest ways to improve treatment under admittedly challenging conditions.

To date, the new registered nurse has been hired and has been working in the county jail for six-to-eight weeks. It’s his job to chair the jail’s medical advisory committee and its quality improvement committee. Before that, a Wellpath employee chaired these committees. The part-time doctor has just been hired — she has 20 years’ experience in correctional medicine — but has yet to start.

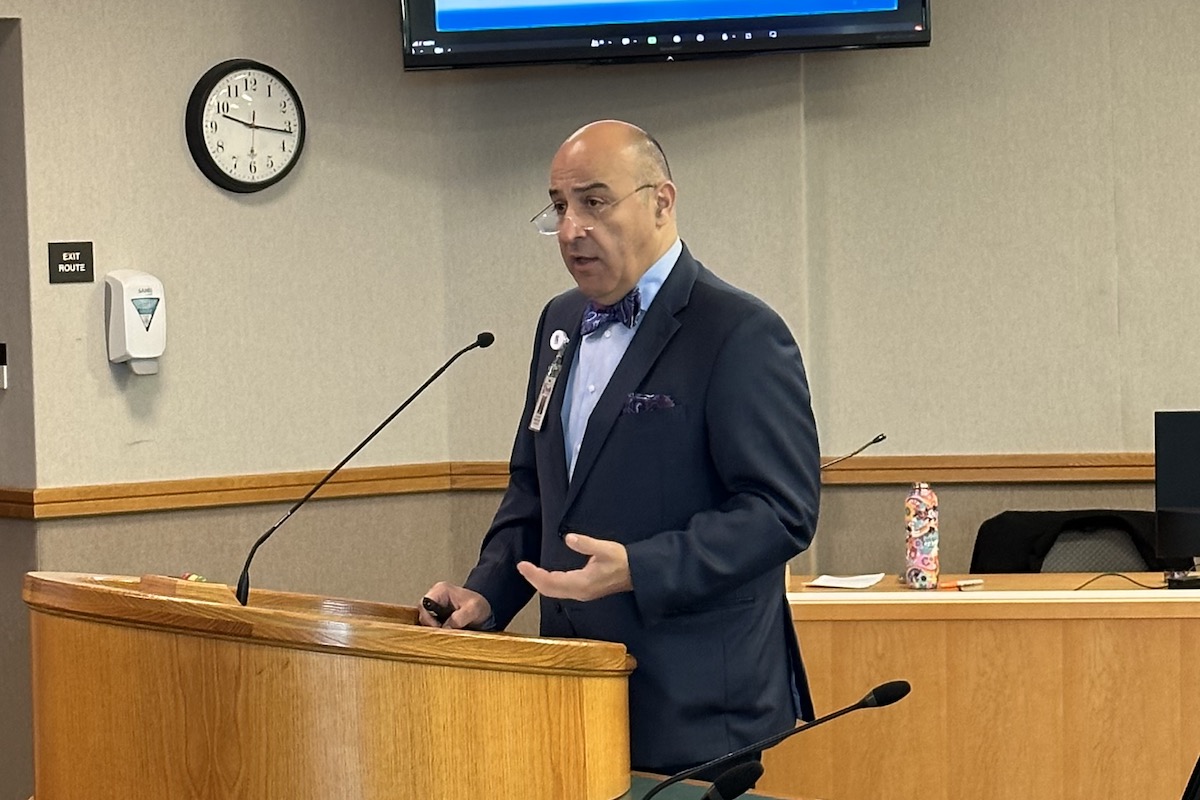

Public Health Director Dr. Mouhanad Hammami said the initial experiences have been positive. He described relations between Wellpath, the correctional staff, and his nurse as “collaborative, constructive, and congenial.”

The county’s bidding process for new medical providers just recently came to a close. It’s not clear how many applicants applied. Anecdotally, it’s said to be a small number. They have yet to be screened by the scoring committee. When that’s done, the ball will once again be in the supervisors’ court.

To the extent the county might have an ace up its sleeve, it’s Hammami himself. Before assuming his Santa Barbara post nearly two years ago, Hammami worked as Public Health Director for Wayne County, Michigan, where he had direct hands-on oversight over three county jails — think the City of Detroit — and a juvenile facility from 2009 to 2015. He knows first-hand how hard it can be.

“It took me three years to hire a psychiatrist, and we were offering three times the going rate,” he exclaimed.

When the supervisors authorized hiring the two new positions, they also instructed Hammami to run the numbers to run the jail himself — how many staff would need to be hired, how much would it cost. He knows how that’s done because he’s done it.

But he’s not itching to do it. There are other major initiatives — one a massive collaboration with the Department of Behavioral Wellness over the mentally ill on the streets — demanding his attention.

“I don’t want to,” he stated flatly. “There will be a lot of challenges. It will be hard. But can we do it? In a word, ‘Yes,’” he said. “If we need to step in, we know what to do.”

His department currently runs five health centers, he noted, three clinics, and a raft of services for homeless people. Three more would not be the end of the world. “It’s not impossible.”

Hammami praised Brown, calling him both a good friend and partner. “I don’t want to step on anyone’s toes here,” he said.

When Hammami started out his medical career, he spent 12 years doing pediatric research. Running a jail health program was the furthest thing from his mind. When he heard Wellpath declared bankruptcy, his first reaction was “I don’t know. It’s too early to say.” His next reaction was different. “If something no longer works, there has to be a better way,” he added. “Maybe this is the time.”

Premier Events

Sat, Jul 26 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Pink Floyd Laser Spectacular LIVE present SHINE ON

Thu, May 01 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

May Day Strong: Santa Barbara

Sat, May 03 9:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Fun in the Sun Walk & Roll for Inclusion

Sun, May 04 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara, CA 93105

Santa Barbara Fair & Expo

Wed, May 07 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Cheese the Day! May 7 and May 14!

Wed, May 14 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Cheese the Day! May 7 and May 14!

Mon, Jun 16 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara