The 50th Anniversary of Aldous Huxley’s UCSB Lecture Series

Remembering a Genius in a Tourist Town

Among Santa Barbara’s finest rumors are some crazy stories about Aldous Huxley living here. Some maintained that the author of Brave New World and Crome Yellow once dwelled in Isla Vista, and whilst across the channel was inspired to write Island. Another tale held that Huxley’s wife would annually procure him a virgin from the then-new UCSB campus for a springtime ritual cloaked in obvious pagan and erotic possibilities. Some rumors suggest that Huxley called the Upham Hotel home while teaching a class at the university, others that his series of lectures became all the rage, spilling audiences out from the auditorium located where UCSB’s lagoon-hugging UCen now stands.

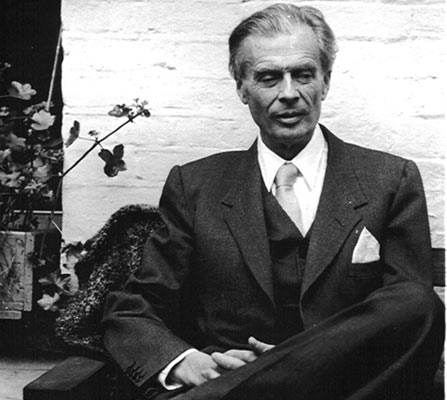

Actually, the last story is true. The other tales, not so much. It’s true, though, that 50 years ago this month, the university hosted Huxley as its first visiting professor. Besides teaching courses to a select corps of English majors, Huxley gave a series of wildly popular public lectures which can be revisited on tape and in a hard-to-find paperback volume barely available on Amazon. In the talks, Huxley isolated major points that would later engage my generation in angry debates as well as stoned ruminations. Would the future belong to B.F. Skinner’s brand of scientific determinism or Timothy Leary’s mystical adventure? What does it mean to be human in a pervasively technological culture? How can we talk about the future under mushroom-clouded skies?

“I deliberately kept the title of this course as vague and as general as I could,” Huxley declared in his February 9, 1959 intro lecture, “so as not to commit myself too far in advance or to pretend that I know too much.” Modestly titled “The Human Situation,” the lectures today seem remarkably prescient, opening with overpopulation, pollution, and their plausible effects on the climate, and concluding with an intriguing inventory of human possibilities. Besides clearly helping to brand Santa Barbara as the eco-friendly New Age paradise it is today, Huxley in 1959 anticipated language that would not be employed by trendy professors, tree-huggers, and San Francisco hippies for at least another decade.

Forward into the Past

Not everybody was enchanted by the author, essayist, and lifestyle pioneer. The well-known S.B. actor George Backman was one of the English majors who took the class. “It was very boring stuff,” he said. “He was so blind he held the notes up practically to his face, and he read all the lectures. Isherwood was much, much better.” Nevertheless, Backman remembers that the public talks needed loudspeakers outside for the overspill throngs.

Who knows why the people came? The talks were made possible by UCSB Proust professor Douwe Stuurman-a khaki-clad, ascot-wearing character about town-who had attended Oxford’s Balliol College with Huxley and Isherwood. But it wasn’t just Anglophilia that made Huxley a hot ticket. His talks fit the agenda of a once-sleepy tourist town that suddenly had a UC campus, appealing to both academics and the greater community. First, Huxley made an impassioned plea for remarrying the increasingly specialized branches of Academia. He wanted people to see the world as a combination of “atomic physics” on one hand and “an immediate experience of value, love, and emotion” on the other. “The building of this fundamental bridge is an urgent, urgent problem in our world,” he said.

He then called for “more Nature in art”-he found the contemporary art of his era too theoretical, and would have loved the Oak Group which formed some 30 years later. But more to the point, he wanted to reclaim moral life on a biosphere. “Th[e] ethical point of view in which nature is regarded as having rights, and we are regarded as having duties, is not found within the Western tradition,” he rightly complained. “Instead we have what seems to me a rather shocking formulation : that animals have no souls. Therefore they have no rights and we have no duties toward them, and consequently they may be treated as things. I feel that this is a most undesirable doctrine.” It’s hardly what you would’ve read on an op ed page in 1959, though I’d venture to say that it’s a notion most Santa Barbarians today, from Wendy McCaw to Marty Blum, would probably embrace.

Braving the New World

Huxley was born in 1894, and grew up into the guttering half-light of World War I England after losing most of his eyesight and his beloved brother. His fame came early in bitingly satirical novels like Crome Yellow, not through family fame, but through sheer hard work. Trained to teach, he was soon dissuaded away from that profession and toward fiction and began by promising his publisher two books a year, all the while traveling and making friends like D.H. Lawrence and Bertrand Russell. Attaining popular infamy by 1931 after the publication of the excoriating sci fi dystopia Brave New World, Huxley came to Southern California, where he mixed literature and science into a pursuit of transcendent experience. He was a member of the Vedanta society and a friend of Krishnamurti in Ojai. He first took psilocybin mushrooms in Mexico, and was given LSD in 1955. He wrote simply and beautifully about the experience in The Doors of Perception, a slender book that became a counter-culture Bible.

The UCSB lectures reveal Huxley’s hard-won acuity as well as his humanity. Huxley was a pacifist, and he devoted a hard hour of thought to underscoring why Marx was so wrong about the proletariat, who did not join across borders and resist fighting during World War I but died for nationalist systems that were crushing them. Huxley was also fascinated by language acquisition and the difference between nature and nurture in the formation of our ethical selves. His essay on the Unconscious makes a lucid attempt at understanding why we use linguistic and amoral constructions like, “I don’t know what came over me,” and, “I wasn’t myself.”

Best, however, reading these lectures opens a door to the group mind of our city. In 1959, though the university had barely 2,000 students, Santa Barbara was a budding intellectual oasis. There were citizens of note already assembled here: the great critics Hugh Kenner and Marvin Mudrick, poets like Edgar Bowers, the crime writer duo Kenneth (Ross Macdonald) and Margaret Millar, as well as artists like Howard Warshaw. Beatniks had opened the Somnambulist Coffee House near the Lobero, and future hippies were establishing space on Mountain Drive. Huxley was a friend of Robert Hutchins of Montecito’s Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, as well as of Igor Stravinsky, who helped found the Music Academy of the West.

Huxley ended his UCSB lecture series in late spring with a plea for objectivity drawn from Oliver Cromwell: “I beseech you from the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.” It’s a quote Huxley believed should be inscribed on every pulpit and lectern in the land. Fifty years later, though, maybe his own radical words spoken a few paragraphs earlier serve better as dessert: “If we all had the doors of our perceptions cleansed and we all saw the world as infinite and holy, we should all find it a great deal less necessary to go in for bullfighting, attacking minorities, or working up frenzies against foreign people.” That would be a brave new world we could start right here.

4•1•1

Tapes of Huxley’s 1959 UCSB lecture series can be heard for free at the university’s Special Collections Library. Call (805) 893-3062 or visit library.ucsb.edu/speccoll. A limited number of copies of the lectures are also available in book format on Amazon.com.