Romancing the Indian: The Photographs of Edward S. Curtis.

At the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Shows through April 6.

For more than 30 years at the beginning of the 20th century, the Wisconsin-born, Seattle-based photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis wandered the expanses of North America interviewing and photographing its native inhabitants. Curtis lived among various tribes, not just observing and documenting the lives of his subjects, but participating in them. His endeavors ultimately yielded a comprehensive and emotive body of work representing some 80 Native American tribes. This vast pictorial legacy was published between 1907 and 1930 in The North American Indian, a 20-volume work.

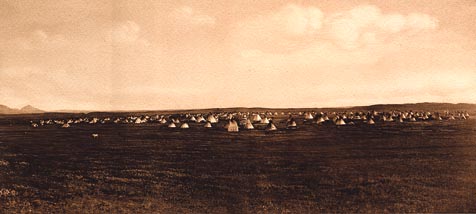

Currently on display at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History is Romancing the Indian, a selection of photographs from Curtis’s oeuvre. The images range from tightly cropped portraits to subjects that are all but consumed by grandiose vistas, yet his work is unified by a signature style. Soft-focus imagery crafted by natural light produces a sympathetic tone in portraiture and landscapes alike.

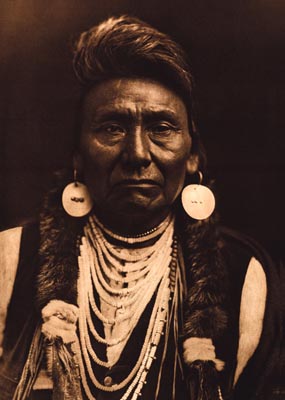

In one photograph, three members of the Sioux Tribe are depicted on horseback, riding defiantly through their territory’s inhospitable badlands. In another, a Piegan Sun Dance encampment sprawls across an endless plain. In many of these depictions, Curtis captures human subjects dwarfed by their environment; such scenes speak of the powerful influence of the natural world upon the lives and routines of its early inhabitants. Curtis captures warriors on the trail, women gathering seeds, fishermen with their nets cast wide, and villages on the move. In his portraits of luminaries like Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce and Geronimo of the Apache to those of a Wishham bride and a Zuni girl, Curtis captures images at once intimate and romantic.

To what degree these images are historically honest has long been a source of contention. Curtis often staged his subjects for effect, sometimes even dressing his subjects in garb that ethnologists believe to be historically inaccurate. In this exhibit, for example, the same leather garment is worn by three separate subjects in different settings and periods. Yet the fact remains that Curtis produced a body of work unparalleled in terms of its range and depth, full of iconic images that capture America’s native people at the end of an era.