‘Can you give me some background on the artist Frank Morley Fletcher?’

-Hattie Beresford

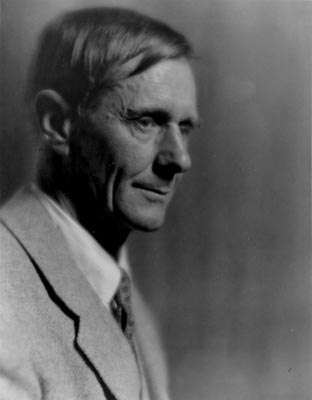

One of the most important cultural institutions in Santa Barbara in the 1920s and early 1930s was the Santa Barbara School of the Arts. The faculty included some of the finest artists in the country and many of the students went on to forge national reputations in their own right. The director of the school during its period of greatest success and influence was Frank Morley Fletcher, known primarily for his role in introducing Japanese colored woodcut printing as an important genre in Western art.

Fletcher, a native of England, was born in 1866 and studied at a number of art schools in his homeland before matriculating at the famed Atelier Cormon in Paris. There he met fellow artists Albert Herter and Fernand Lungren, compatriots who one day would convince Fletcher to settle in Santa Barbara.

Fletcher’s time in Paris coincided with a period in which many European artists were being influenced by the techniques and aesthetic of the Japanese color woodblock print with its abstract elements and soft, subtle colors. Fletcher was deeply impressed by this imported Asian medium and, while adding a Western slant to it, made it his own. One important innovation he championed was to rest the responsibility of the entire woodblock printing process in the hands of a single artist. This contrasted with the Japanese tradition of dividing the process among four specialists.

Upon his return to England in the late 1890s, Fletcher launched his career as an educator, teaching printmaking while still perfecting his own style in Japanese woodblock art. Fletcher’s proselytizing was highly influential. In addition to his classroom instruction, Fletcher wrote a number of articles as well as the book Wood-Block Printing (1916), a detailed guide to the medium. In 1923 he was teaching at the Edinburgh College of Art, an artist of international reputation, when he heeded the call to Santa Barbara.

The Santa Barbara School of the Arts was founded in 1920 under the presidency of Lungren, a famed landscape artist. During its early years, the school offered courses in art in the broadest sense with instruction in painting, photography, dance, interior design, the theater, and more. The school kept tuition to a minimum and had a very active outreach program with lectures, recitals, and exhibitions, all with the idea of encouraging maximum community involvement. Members of the fine arts faculty included Lungren, Herter, Carl Oscar Borg, and Edward Borein.

Fletcher came on board as school director in 1924 and under his guidance the curriculum began to more heavily emphasize the visual arts. Fletcher was more than an administrator; he introduced color woodcut printing, almost unknown on the West Coast at this time, to the course offerings. Fletcher thought of woodblock printing as a “democratic art” that was a fine fit with the school’s emphasis on broad-based community participation. Students mentored by him who went on to careers in art, and became proficient in woodblock printing, included Campbell Grant, Channing Peake, Richmond Kelsey, and Joseph Knowles.

The last half of the 1920s was the high-water mark for the fortunes of the School of the Arts, with attendance approaching 300 students. The school was at the center of the city’s cultural vitality and was a major factor in Santa Barbara’s status as an important artistic colony. The good times, however, would not last.

The onset of the Great Depression saw a shrinkage in grant monies and other funding

and a decline in enrollment as scholarships dried up. By 1932, enrollment was down to 100 and the school would limp along, close, re-open, and then finally shut down for good in 1938. Fletcher resigned as director in the spring of 1930 and eventually moved to Los Angeles where he continued to teach, paint, and exhibit. In the late 1930s his eyesight began to fail, his output became more sporadic, and he then moved to Ojai in the early 1940s where he died in 1949. The method of woodblock printing that Fletcher had championed fell out of favor for a time, but interest in the process has renewed and Fletcher’s importance has been recognized, as has his place in Santa Barbara’s cultural history.