Will the Central Coast’s Alternative Energy Businesses Survive Downturn?

The Carrizo Plain's Topaz Farm, World's Largest Solar Panel Project To Be, Is a Test for the Rest

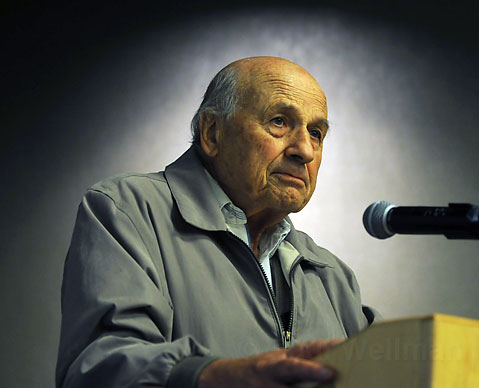

Carissa Plains, from an open house in April 2008

Carrizo Plain, in southeastern San Luis Obispo County, is a sprawl of gently rolling hills. Bathed in sunlight most days of the year, it is California’s largest native grassland. Since 1970, it has also been one of the most popular locations for solar power projects in the United States.

In July, a little-known Bay Area solar technology firm, called OptiSolar Inc., asked officials in San Luis for permission to build the largest solar panel project in the world on nine acres of leased agricultural land in the northern corner of Carrizo Plain. The Topaz Solar Farm would generate an enormous 550 megawatts of power-enough to provide over 200,000 homes with electricity.

Prospects for the Topaz project have been promising. It is likely to pass the necessary local and state bureaucratic hurdles, and in August, OptiSolar signed a contract with Pacific Gas & Electric, in which the utility agreed to buy and deliver the electricity produced by Topaz Farm.

And yet, like alternative energy projects around the country, the future of Topaz Solar Farm has been brought into question by the world financial crisis. As a startup, albeit a large one, OptiSolar is going to need to get its hands on a great deal of capital. A company spokesman declined to specify the estimated cost of the project-which OptiSolar will build, soup to nuts-but it is almost certain to exceed $1 billion. The current seizing up of credit and private equity investment could make raising such a sum difficult.

Since Wall Street began its downward spiral in earnest, in mid-September, more and more attention has been paid to health of the market for alternative energy, which in recent years had expanded rapidly. This growth was driven by high oil prices, combined with the growing consensus, nationally and internationally, that serious action must be taken to combat climate change, by reducing the use of carbon-emitting fossil fuels. California, which announced a goal of reducing total carbon emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, is in the vanguard of efforts to shift toward renewable energy sources.

Many observers are speculating that the alternative energy industry is facing a serious downturn. Energy analysts are worried about the credit freeze and the recent sharp drop in the price of oil, along with the possibility that federal funding will diminish as a consequence of the fiscal burden created by the financial crisis. According to a recent story in the New York Times, financing for alternative energy projects fell to about $18 billion in the third quarter, compared to over $23 billion in the second. It’s likely to fall even further in the fourth quarter. The Topaz Solar Farm represents by far the most ambitious solar energy project ever proposed; whether it comes to fruition could be a bellwether of the industry’s health as a whole.

Silver Linings: In conversations with a handful of local clean energy entrepreneurs, academics, and environmentalists, a surprising theme emerged: The current economic turmoil, while gravely worrying, may not cause a long-term downturn in the growth of the clean technology industry. Indeed, there was a surprising willingness to engage in cautious optimism-a welcome respite from weeks of nasty headlines. A loose consensus materialized: The economic crisis might actually prove to be a big opportunity, a historic shake-up that could provide the impetus for a transformation in the way Americans view the energy infrastructure of the United States.

“The clean tech sector has been one of the last [industries] to be hit by this financial crisis, and I think we’ll be one of first to recover,” said Rick Margolin, who is managing director of Innovo, a local clean technology consulting firm. Margolin did not deny that the industry for renewable energy sources is facing serious challenges, and he said he is particularly concerned by the dramatic fall of oil, down to $67 per barrel. Though anyone who owns a car may be hard-pressed to find fault with this development, Margolin pointed out that for most of 2008, while oil prices were high, energy conservation reached record levels, as did investment in the clean technology industry.

Still, Margolin argued that the clean tech market will weather the current crisis for a simple reason: Petroleum and natural gas are drying up. That, combined with the necessity of reducing world carbon emissions in the fight against climate change, means a permanent demand for renewable energy. “There’s very good financials in the clean tech sector,” he said. “The demand for renewable energy is real. The price of oil is going to go back up. It’s just simple geology, and supply and demand.”

Everyone interviewed agreed that for the clean technology industry to continue growing, local, state, and federal help is necessary. There was disagreement about Proposition 7, which would require California utilities to procure half of their power from renewable resources by 2025. Tam Hunt, who is energy director of the Santa Barbara Community Environmental Council, supports it, but many other environmentalists do not, including the Sierra Club; opponents say the proposition is poorly written and riddled with loopholes.

Everyone agreed that both presidential candidates appear to be committed to directing significant federal resources toward clean energy, although McCain’s support for nuclear power, and both McCain and Obama’s support for clean coal technology and off-shore oil drilling were derided as counterproductive. As Walter Kohn, a Nobel Prize winning chemist, and UCSB physics professor, put it, “Clean coal is an oxymoron.” Forced to choose between the two, on the basis of their energy policies, all picked Obama. In the last Presidential debate, Obama said that weaning the country away from our dependence on foreign oil is “the most important issue our future economy is going to face.”

There was also agreement that for alternative energies to thrive in coming years, the federal government must end or substantially reduce subsidies to oil and natural gas companies. Both industries are heavily subsidized. “On the one hand, we’re propping up those industries, and on the other hand we’re complaining about how we’re so dependent on those industries and how we really need to develop alternatives,” said Rick Margolin. “It’s two policies that cancel each other out.”

Kohn lauded Santa Barbara’s, and California’s, efforts to embrace alternative energy. “We here in California have been a model for the rest of the nation in terms of recognizing the urgency of the climate problem-and not just recognizing it, but doing something about it,” he said. Kohn hopes that the current economic crisis will force Americans to reconsider the basic nature of the country’s attitude toward energy. Without a wholesale shift away from fossil fuels, he said, we’ll be stuck with even worse economic problems in the future, as oil, natural gas, and coal become scarcer, and the greenhouse effect intensifies.

Kohn’s colleague Oran Young, a professor at the Donald Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at UCSB, said he was at least willing to be optimistic about the prospect of institutional change. “Crises can be periods of opportunity,” he said. “When entrenched systems and entrenched organizations collapse, dramatic changes that seemed hopelessly unrealistic in other times, begin to seem feasible.” Young believes it’s not outside the realm of possibility that, especially in the event of an Obama presidency, the nation will embark on 21st century equivalent of the New Deal, only this time directed toward revamping its energy infastructure.

Either way, Young emphasized, the immediacy of the economic crisis should not lead Americans to discount the necessity of fighting climate change now; he said it’s dangerous to think that climate change is a future problem that can be dealt with when the country-and the world-is on surer financial footing.

But he ended on a positive note. “Responding seriously to climate change will be costly. But it won’t necessarily be all that costly in macroeconomic terms. Dealing with climate change effectively is going to create all kinds of economic opportunities-opportunities for new businesses, jobs, and so forth. Some of the existing major players in the economy will have to adapt in a very drastic way, or they will go out of business. But, there is nothing new or radically different about this than other periods of history.”

His argument is backed up by a newly published study by the University of California: California’s energy-efficiency policies created nearly 1.5 million jobs, from 1977 to 2007, while eliminating fewer than 25,000.

The Boon in the Bailout: Fortunately for OptiSolar, which is funded by private equity (much of it from Canadian financial institutions), it has some breathing room on the Topaz Farm. Construction on the project isn’t scheduled to begin until 2010, at the earliest, leaving time for a potential rebound in the financial markets. “We expect the permitting process to go on for a year or more,” said Vice President of Communications Alan Bernheimer. “You don’t start your project financing until you’ve got all of your permits. So we’re in the fortunate position of being able to wait and hope the financial markets have regained some health by the time we need to go out for project financing.”

Paradoxically, the financial crisis has been, in one narrow but important respect, a boon for the American solar industry, and for the prospects of the Topaz Farm. For many years solar projects in the U.S. have been the beneficiaries of a federal tax subsidy, called the solar tax credit, which makes a 30 percent tax credit available for commercial solar installations. The credit was set to expire at the end of 2008, and in the last year supporters in Congress tried repeatedly-and failed-to renew it. But then came the federal bailout of Wall Street. One of the “sweeteners” added to the bailout package in its second Congressional go-round was an eight-year extension of the solar credit. (There was also a one year extension of a similar credit for windpower). In fact, Congress even removed the $2,000 cap on the credit.

The Community Environmental Council’s Hunt offered a vigorous and convincing argument, dense with statistics, that renewable energy will weather the economic storm, particularly in California and Santa Barbara. It is certainly true that the extension is a huge windfall for OptiSolar, which should now be able to find an equity partner-one with a lot of tax to pay-to fund at least 30 percent of the Topaz farm. “This removes a huge, huge uncertainty, and it’s very welcome news to us and everyone else in the solar industry,” said Bernheimer.

Traditionally, investors in big alternative energy projects have been banks, insurance companies, and the financial arms of big industrial companies, such as GE’s Energy Financial Services arm. But according to Nathaniel Bullard, an energy analyst with New Energy Finance, a London research firm, that’s changed, at least for now. “Obviously [those companies] have had something of a rough year, and in some cases they may not have much of a tax appetite,” he said. Bullard believes that when financing time comes around in a year or two, OptiSolar will be able to find an equity partner-someone to pony up 30 percent or more of the total cost of the Topaz Farm-and that that equity partner may well be a major oil company. As he pointed out, oil companies have a lot of tax, and they have a lot “visibility” on that tax. In other words, it wouldn’t hurt Chevron’s public image, for example, if they owned a chunk of the largest solar power farm in the world.

Still, even in the event OptiSolar is able to find an equity partner with relative ease, it is not altogether certain that in a year’s time, or even two year’s time, it will be able, or willing, to take on the debt required to finance the rest of the project. As this story is being written, former Federal Reserve Chairmen Alan Greenspan is testifying before a Congressional finance committee. “Given the financial damage to date, I cannot see how we can avoid a significant rise in layoffs and unemployment,” he told the committee. OptiSolar has at least a year before it has to start figuring out how to finance the Topaz Solar Farm. Fans of alternative energy, in San Luis Obispo and beyond, must hope that’s time enough for the alternative energy market-and world financial markets-to recover from their current woes.