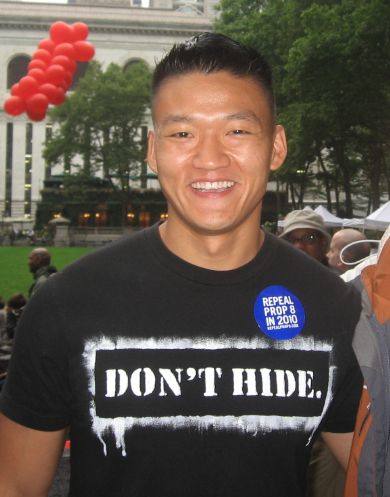

Lt. Dan Choi Talks Camp Courage

Gay Rights Activist Explains the Dignity that Comes with Honesty

Dan Choi rose to national prominence last March when he declared on The Rachel Maddow Show, “I am gay.” What makes his very public coming out so revolutionary is that he is in the Army, and thus his honesty defies the military’s policy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Since then, Lt. Choi has become an articulate force within the gay rights community in addition to cofounding Knights Out, an organization of fellow West Point grads and staffers who oppose that policy.

But Lt. Choi, an Arabic translator who served an extended tour in Baghdad in 2006 and 2007, also was sent a discharge letter, making him one of the 12,500 servicemembers who’ve been kicked out of the military since that policy came into effect in 1993. Signed into law by then president Bill Clinton, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was Clinton’s attempt to appease all sides of the discussion regarding the ban on gays serving in the military. Throughout the years, it has become one of the biggest frustrations for those fighting for equal rights on the home front —as the U.S. sends troops to fight for freedom and justice on foreign soil, some 65,000 se rvicemembers are themselves denied the ability to live honestly because they are gay.

Before he became the poster boy for the maddening hypocrisy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Lt. Choi was a member of the Courage Campaign, a progressive, grassroots activist group started by Rick Jacobs. Lt. Choi has been outspoken against California’s Proposition 8, and has been very involved with the organization’s Camp Courage, a two-day workshop that teaches supporters of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights how to cultivate the communication skills needed to persuade people of the importance of equality.

Camp Courage comes to the Central Coast on January 30-31 at Santa Barbara City College in the first-ever tri-county gathering, and, in anticipation of that event, Lt. Choi phoned in to The Independent to talk about the importance of activism and being true to oneself.

Can you talk a bit about your involvement with Camp Courage?

I’ve actually been a member of Courage Campaign since Prop. 8 happened, and I started getting involved with marriage equality activism particularly in February and May during a lot of the fallout from the court case. Of course, that predates any involvement with Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell conversations.

Rick Jacobs contacted me and we decided to publicize the letter I wrote to President Obama about the disaster of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, and then it really picked up in a lot of ways. I think there are a couple of threads that we’ve tied together just by doing it and by working with amazing people like Rick, and the Camp Courage people especially. I’ve learned a lot, and things I didn’t even consider, like the fact that I’m a racial minority as well as the son of an immigrant, are things I think the progressive movement, as well as the conservative population in California, can relate to. It’s been a very educational experience, for me, to understand a lot more about our message.

I went to Camp Courage in Sacramento as well as to East L.A., and I shared a message. Initially, the message was just about Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and military discrimination. But when I got to share what we learn at Camp Courage is one’s “story of self,” our own personal narratives, I realized that there are a lot of aspects of my personal history that have played into why I became an activist, and a lot of it does include my Army training. I would liken a lot of the things Camp Courage has taught to a lot of the values that the Army tries to inculcate, and I think Camp Courage does that brilliantly. It really just says, “You have to stand up for who you are,” and, “Your fears and your human tendency to hide and to be comfortable are the things that make our movement and our society absolutely weak.”

A lot of people have a sense of worthlessness, particularly within the LGBT community just because of the way society has set up judgment against us. Camp Courage really turned that on its head, and says that the sense of worthlessness and that hiding is what makes you worthless. When we break through that, even with all the consequences — particularly with me, the consequence of getting kicked out of the military — some of us feel like we’ve been stripped of our dignity. But us just standing and sharing that story, that is our dignity in itself. And so that’s really the message that I’ve tried to portray to a lot of people as much as possible — there is so much strength in that very simple value of honesty and integrity. I’ve realized that parts of my identity help me to spread that message in different ways, and they build a platform, in a way, so that I can communicate to a wide array of people. But the basics of it all, the foundation, is the fact that when you stand up, you confer that dignity upon yourself.

It’s a very simple thing—just saying, “This is who I am.” But it’s so powerful.

That’s right. There’s also power in the community and the company you keep during that weekend. It resembles church in a lot of ways — we’ve all come together for this express purpose, and there is fellowship. My dad was a Southern Baptist minister and I was raised in the church, and I talk about that a lot now, and am more comfortable talking about it. It’s basically everything of church, except the praise and worship team’s not there, and we don’t take communion. But there are a lot of similar aspects, and especially for people who’ve been rejected by their churches, it’s great to see some of those very foundational principles being hit on. And when we return to that, it’s very, for us, refreshing. There is absolutely no dissonance — that is to say, the values we learned from the very beginning can be applied to our activism. And it’s not just that they “can be” applied, but they’re the basics of the activism as well.

Do you feel like the Camp Courage model is a good jumping-off point for other movements to base their activism training on?

Absolutely. You know, it’s not just in its simplicity, but in the overall precepts. The thing I’ve learned in activism is that every action breeds more action, whether it’s complex or basic. You never know when one thing you say, you might not even intend for it to be your thesis or climax, but it’s what somebody will latch onto. I’ve been surprised a lot by some of the things I’ve said — wow, I didn’t even mean for that to be the rallying point, so to speak, but someone will just come and tell me on my Facebook, “Oh my God, I can’t believe what you said! That was so great, and that was my jumping-off point.” The point is, we never know what can be the jumping-off point for someone else, and that’s why we have to continue doing all things. Because Camp Courage is so basic and so foundational, it does give people that tool, like the bedrock tool.

If we base all of our decisions on our foundational values, then you can never go wrong. That’s the beauty and the strongest asset of Camp Courage is that it will remind people: This is your true north, this is your compass. We might disagree on specific tactics or some people might have certain skills or resources in one area; especially within our community, there’s so much action in all different directions, that it can seem disunited, like we’re all over the place and we’re disagreeing with each other. And at times we are. But as long as we stay grounded in those values — just like the Army does, when you say the seven Army values of loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, personal courage — those are the things you fall back on. They might be general, but when you think of it in those terms — and you’ll always have differences in ways people handle things — and you base it on that foundation, you cannot go wrong.

What do you see as the future of gay rights activism?

I think we have to be very careful when we compare our activism or our movement to other movements. When a lot of people ask those predictions, we are so quick to go back to Martin Luther King, or to Gandhi, or perhaps even to Moses. But we have to remember that each movement had its difficulties with this idea of creating one strong group. Militarily, if you’re asking me about strategy—which essentially is your question: gay rights, activism, and strategy — unity of command is essential. A lot of my rhetoric tends to divert back to that, probably because of my training, and I talk in terms of principles of war. But they’re not always fully applicable in a direct way.

We can have all this legislation and we can have all these successes in the courtroom or in Congress or even in the executive branch or the bureaucratic level, and those are measureable. But the true measure for me, when I think about my work and this activism, is are we capable as individual gay people in the world to live honestly, and how have we progressed in the ability for people to come to terms with themselves. So when you look at that very noble end state, then every single thing we do, even if we seem disunited, is working toward that.

If you think just in terms of if the activism is going to the end of having legislation, then, sure, you can think of it in terms of lobbying. You can look at the other lobbies and see other constructs and the constraints of our particular political system. But my goal from the very beginning is to tell every soldier—and of course that’s applicable to every Southern Baptist, or every Asian-American, or every gay person in America and the world — that you are honorable. When we can make that message very clear to all these people, I think, in the end, that is much more important for us as a community, to have that dignity. Are we there yet? I think we’ve come a long way in that goal.

We can’t knock the fact that one of our strengths is our ability to be — and it’s very clear that we are — ubiquitous. In every cultural group, in every profession. And that’s markedly different from Gandhi’s situation, where you had a distinct colonial power and Hindu and Muslim people who were oppressed. In the black civil rights movement, there were very distinct groups of people who even lived in segregated areas. With us, it’s different. I would say that’s one of our gifts — we’re in the military, we’re in corporate America, we’re in the media, we’re in the churches, we’re in the ghettos. In each of our communities, we have to build that very common denominator — how do we increase the dignity of each and every person?

Is there anything you’d like to say to folks on the Central Coast who might be on the fence about attending Camp Courage?

If you’re thinking of it in terms of the amount of time you’ll spend, you have to realize that this can be, for you, life-changing. And I’m not talking about your own life. I’m talking about the people you will affect with this. I think when you are deciding whether to be there or not, it’s not just about what you can gain from it, but what you will be able to effect in the lives of others. Just being there, you will be able to contribute in that way. So that should be the motivation, and of course that will be fostered while you spend just a few moments there. You’ll be in an area where you might be overlooking an ocean, but this is your chance to be a part of this tidal wave.

4•1•1

Camp Courage comes to Santa Barbara Saturday, January 30, and Sunday, January 31, at S.B. City College. If you are unable to attend both days but still want to be involved, volunteers are needed for four-hour shifts throughout the weekend. Space is limited, so visit couragecampaign.org/campcourage to sign up today.