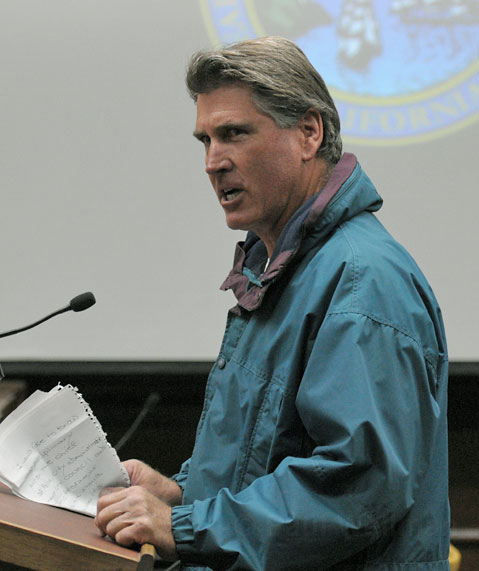

Das Williams Bows Out

Ends Where He Started — Debating Living Wage

Das Williams spent his last meeting as a member of the Santa Barbara City Council pretty much where he started his City Hall career, debating the City of Santa Barbara’s Living Wage ordinance. But before that happened, he got a sweet earful from his friend and political colleague Mayor Helene Schneider — she relied upon Williams to play “bad cop” to her good one — who gave him a proclamation recognizing his contributions to the city during nearly two terms of office.

Williams is cutting short his council term by one year, having just been elected to the State Assembly in Sacramento. He gets sworn in December 4, which happens to be the Feast of Saint Barbara, the city’s namesake. “Good luck in Sacramento,” said Schneider. “I know you’ll need it.” Williams expressed gratitude for having been given the opportunity to serve, adding, “I hope you will call upon me to work with you.” Schneider, who was first elected with Williams in 2003 as part of new wave of younger upstart activist Democrats, retorted, “As I told you earlier, we all have your cell phone number.”

Not all was quite so harmonious, however. Councilmember Dale Francisco, with whom Williams has famously feuded, was notably absent when Schneider made her laudatory remarks. Whether coincidentally or not, Tuesday’s council meeting happened to draw a higher percentage of Santa Barbara’s political gadfly community than normal, eager to take advantage of the “open mike” portion of council meetings open to unsolicited and un-agendized public comment. Kate Smith, a dramatic if poetic critic of what she terms the “school-to-prison pipeline,” left Williams with a parting zinger. “You have betrayed us with your silence,” she charged.

Wayne Scoles, the outspoken Mesa activist who was arrested for verbally threatening Police Chief Cam Sanchez several years ago — but was found not guilty by a jury — complained Santa Barbarans are no longer safe from “violent bums, Latino gangs, and police officers who abuse their powers.” Scoles sued city hall for civil rights violations after the jury found him not guilty, but a federal judge tossed his case out of court. Scoles vowed to come back later to tell the council of his dealings with the FBI and Justice Department, which he said was investigating these allegations. “I guarantee you have not seen the last of me,” he said. Williams in his new political incarnation, however, will not be there when that happens.

“Tennisance Man” Kenneth Loch gave a brief discourse on the benefits he experienced by learning to play tennis while holding rackets in each hand. He said the competitive pursuit of tennis was not healthy for the community, and suggested that such a “parading shift” would be good for the entire area. Like Scoles, Loch pledged to elaborate at future council meetings. “I’ll be getting into that,” he promised. Jeff Wood, recently arrested for selling medical marijuana illegally, was more pointed in his remarks about Williams. He charged that Williams ignored warnings he delivered more than a year ago that a neighbor of his at an Eastside mobile home park was illegally dumping orchid fertilizer into the creek. “This orchid fertilizer is breeding mosquitoes that kill,” he warned. Because Williams shined him on, Wood said he’ll take his concerns to the FBI. Williams replied only that the city’s Creeks Division would be a more appropriate government agency.

There was more than tidy symmetry to the fact that Williams’s last meeting would deal with the Living Wage ordinance. Even before being elected to the council, Williams was among the ringleaders of the campaign promoting a Living Wage ordinance targeting employees of private companies hired to fulfill service contracts by city hall. Once on the council, Williams found himself not only voting in support of the measure but legislatively crafting fine details of what was a politically contentious issue. Addressed this Tuesday was a report, long languishing, on the actual costs and benefits of Santa Barbara’s Living Wage law and ways it might be improved. That the report finally made its way to the council before Williams stepped down was no accident. With Williams there, there was narrow majority of councilmembers who could be counted on to beat back any push by the council’s conservative minority to reconsider the Living Wage ordinance or eliminate it altogether. And after some lengthy debate on the matter, that’s exactly what happened.

The report itself raised far more questions than it answered. Based on the findings, it’s hard to tell how many people have actually benefited from the ordinance — lifted out of a life of wage-slave poverty, as proponents predicted — or to what extent it’s become the scourge of free enterprise — as opponents had warned. City hall defines a living wage as $15.45 per hour for people with no benefits and as low as $12.14 for those provided an ample benefit package. This requirement is imposed on private businesses contracting with city hall to provide such services as late-night janitorial work. The requirement is triggered only for bigger contractors, those receiving $16,548 or more a year. That universe includes 98 businesses.

“What I see here is the typical proliferation of complications that arise when a city government decided to step in and prevent perceived injustices by interfering in a process it really doesn’t understand.” — Councilmember Dale Francisco

Two years ago, City Hall mailed a survey to the 98 contractors to ask them how the law affected them. Sixty-eight replied. Based on the results, it appears that 83 workers actually benefited by receiving the living wage. Those businesses reported they sought to recoup the additional costs by charging city hall $171,000 more for the same services. According to Bob Samario, city finance director, the city did nothing to obtain independent verification that the employees in question actually were paid the “living wage.” He said that three audits were conducted — at a total cost to the city of $10,000 — and that the books of the companies in question were so jumbled that it was impossible to determine whether they were complying with the law or not. Samario also stated that of the 900 hourly employees hired by city hall, most are paid a living wage. But 311 are not. Were they to receive the same compensation city hall requires of its contractors, it would cost the city $1.1 million more a year.

A majority of the Living Wage Advisory Committee argued the Living Wage had been a success and should, in fact, be expanded. Money should be set aside to audit companies for compliance; violators should be fined $500 — current law does allow the imposition of fines — and the exemptions, for which there are many, should be narrowed. Companies doing business with city hall should be allowed to pay their workers so low, they argued, that they could qualify for state assistance. But Allen Williams, a contractor on that same committee, begged to differ. “The city spent over one-million dollars without a single measurable benefit,” he declared. “It spent $1 million extra to have the same services provided.”

City finance chief Samario disputed the $1 million figure Williams bandied about. Williams added because of the Living Wage law, local businesses find themselves increasingly competing with out-of-town and out-of-county contractors for city contracts. Larger local contractors have to pay a living wage, which he said puts them at a competitive disadvantage with out-of-town operators who, because they haven’t hit the $16,000 threshold yet, can charge less for their services. As a result, Allen Williams said, a San Luis Obispo company is now cleaning up the downtown library. Dick Flacks, a retired UCSB sociology professor also on the advisory committee, objected that Williams had presented no data to back up such claims. If 100 families have benefited because of the Living Wage ordinance, then it was a success.

While many councilmembers had something to say about the Living Wage, the debate was dominated — as always — by Das Williams and Dale Francisco. “What I see here is the typical proliferation of complications that arise when a city government decided to step in and prevent perceived injustices by interfering in a process it really doesn’t understand,” said Francisco. He argued that in a free market, good employers who treat their employees well are rewarded with higher productivity, greater loyalty, happy customers, and more business. Williams shot back that government contractors are not operating in anything resembling a free market. Governmental decision makers are bound by law to select the qualified vendor offering the lowest prices. “That disadvantages contractors who pay better and provide health benefits,” Williams said.

In an interview afterward, Williams said the value of the Living Wage ordinance is not just the number of employees who directly benefit, but the message it sends to the broader community. “I can’t tell you how many people — hundreds — who’ve come up to me and said I want to pay my workers what the city considers a living wage. It’s a statement of values, that we’re not going to do business with people who pay their employees poverty wages.”

Francisco expressed interest either in abolishing the Living Wage ordinance or rewriting it. He was joined in that by Councilmembers Michael Self and Frank Hotchkiss. Joining Williams in his support for the Living Wage was Mayor Helene Schneider and Councilmember Grant House. Councilmember Bendy White — the council’s swing vote — opined, “This is definitely one of those times when the man in the middle feels like the man in the middle.” White said he was comfortable keeping the existing ordinance the way it was, but opposed expanding it in any fashion. Williams and his allies were comfortable with that, so the ordinance stands.