‘White Knight’ Gets Cold Shoulder

Loss of Open Space Sparks Opposition to New Entrada Plan

Two years ago, Los Angeles developer Michael Rosenfeld was regarded around City Hall as the next best thing to a knight in shining armor. That’s when he bought the long languishing black hole occupying three large parcels near the bottom of State Street, a dead zone otherwise known as La Entrada de Santa Barbara.

For 10 years, the conspicuously un-built Entrada project had been the subject of much civic embarrassment, countless empty promises, but no action. Rosenfeld — now in the process of building two 46-story buildings behind the iconic Century Plaza Hotel in Century City — promised an end to the interminable delays. But if last week’s meeting of Santa Barbara’s Historic Landmarks Commission gives any indication, the honeymoon is over.

It was Rosenfeld’s first public appearance in Santa Barbara’s officialdom. He was pitching significant changes to a 123-room luxury hotel development plan that had first been approved in 2001 as a village of time-share condos and then altered again — substantially — in 2009. In person, Rosenfeld was charming, at ease, and in command. Accordingly, the commissioners were duly charmed. But collectively they were not buying what Rosenfeld was selling. To most, more changes meant further delay. And with one exception, the commissioners expressed alarm that Rosenfeld would propose dramatically reducing the amount of public open space the project had promised.

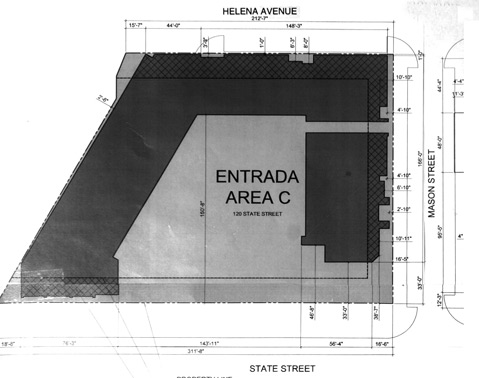

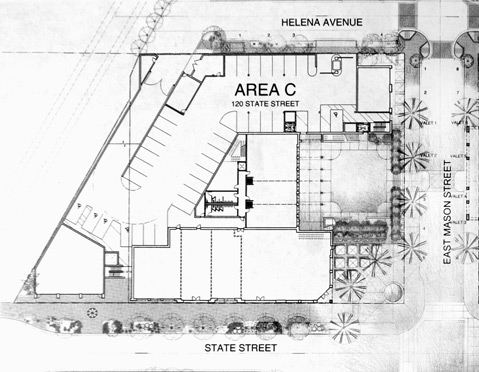

When the previous developer sought major changes to the Entrada project in 2009, the key selling point was an expansive public plaza located at the corner of State and Mason streets — on the mountain side — occupying nearly 20,000 square feet. Without that plaza, the proposed design changes would have been dead on arrival. Depending on which numbers one accepts, Rosenfeld is now asking to reduce that public open space by one-half or by one-third. Either way, it’s significant.

According to Rosenfeld’s attorney, Doug Fell, his client hopes to reduce the public open space on what’s known as Parcel C — a 50,000-square-foot lot that for years has been a fenced-off construction pit across State Street from the Californian Hotel — by roughly 6,000 square feet. But according to estimates released by City Hall, the reduction Rosenfeld has in mind weighs in closer to 9,000 square feet.

Most outspoken was Historic Landmarks Commissioner William La Voie. “What’s left of the open space is a postage stamp in comparison,” he said. “It’s boring; God help you.” Less scathing was Commissioner Michael Drury, who suggested that Rosenfeld’s proposal for Parcel C lacked “the poetry” of the current approved plans.

Technically, such remarks carry no legal weight. But politically, they’re fatal. Rosenfeld has characterized the changes as “design refinements” that are entirely consistent with the plans already approved. By law, the Historic Landmarks Commission has no say whether that’s true. The decision to grant what’s known as a “finding of substantial conformance” rests exclusively with City Administrator Jim Armstrong. Absent such a finding, Rosenfeld will be stuck with the existing plans.

When Rosenfeld bought the three parcels for less than $7 million, he concluded that the approved plans , which called for distributing parking throughout all three parcels, were both “nonsensical” and “non-feasible.” Rather than stage the construction in three separate phases — one for each lot — Rosenfeld is seeking permission to do it all at once.

Rosenfeld is also proposing to mass 10,000 square feet of stores and shops on Parcel C right along the State Street frontage. Under the approved plans, the retail space would be distributed throughout the entire project but set back considerably from State Street. Some critics have suggested this will create a “canyon effect” or contribute to “densification.” Rosenfeld contended that by locating the shops closer to the street, more people would be drawn into the project. Rosenfeld has also proposed adding several conference rooms and meeting facilities to Parcel C. None were included in the approved plans.

Attorney Fell contended Rosenfeld’s critics were looking at the project through the wrong end of the magnifying glass. Rather than focus on how much less open space Rosenfeld is hoping to provide, he argued, they should focus on how much better the project would function than the one now approved. (Fell, it should be noted, represented La Entrada’s previous two owners and played a key role in persuading City Hall to approve the 2009 changes in exchange for the bigger plaza.) Not only would the new proposal be more economically viable, Fell argued, but it would encroach less into building setback space, intrude less on mountain views, and offer more spa space and other amenities.

Tony Romasanta — who owns the Harbor View Inn by State and Cabrillo — is quick to deride La Entrada as “La Mirage.”

Many of Rosenfeld’s critics concede such points. The real problem, they say, is partly the long history of broken promises made by Rosenfeld’s predecessors, who strung City Hall along for 12 years while consigning the surrounding neighborhood to blight. Tony Romasanta — who owns the Harbor View Inn by State and Cabrillo — is quick to deride La Entrada as “La Mirage.” Rosenfeld, he charged, has already missed key deadlines imposed by City Hall to get construction underway. Specifically, Romasanta claimed Rosenfeld missed his deadline to begin construction last October on narrowing State Street — and expanding the sidewalks — between the railroad tracks and Cabrillo Boulevard.

City officials confirmed this, as did Rosenfeld’s attorney Fell. Fell vowed construction would begin “next week,” while cautioning that construction does not necessarily entail shovels and jackhammers. In his remarks to the Historic Landmarks Commission, Rosenfeld took pains to highlight the costs he incurred bringing the Californian Hotel into compliance with seismic safety regulations this summer. That — and the fresh coat of paint he applied to the hotel — should demonstrate his “good faith” as a good neighbor.

Romasanta, who aggressively bird-dogged Rosenfeld’s predecessors, as well, worries that if Rosenfeld gets behind schedule, his construction efforts could exacerbate several major bridge rebuilding projects slated to begin soon in the neighborhood. Should that occur, he charged, Rosenfeld could ruin the summer season for neighborhood businesses. Romasanta, it should be noted, is seeking approval to build a 34-room addition to his waterfront hotel.

The saga of La Entrada easily qualifies as one of Santa Barbara’s slowest-moving train wrecks in which nothing ever happens, so few people pay much attention. But at last week’s hearing, there was an abundance of fresh faces in attendance. In addition to the ever outspoken Romasanta, who kept uncharacteristically silent, there was Jim Westby — a behind-the-scenes mover and shaker in conservative circles. Westby — who has tussled with Fell on numerous projects — provided the commissioners with a graphic presentation showing how much open space would not be included should Rosenfeld’s changes be allowed. He was joined by former city councilmember Michael Self, whom Westby helped elect in 2009. Also present was Councilmember Dale Francisco — a close ally of Westby’s. Francisco didn’t comment at the hearing but afterward stated he did not believe the changes Rosenfeld proposed could qualify for a finding of substantial conformance. What this means for Rosenfeld has yet to be seen, but this year is an election year for the City Council, with three seats up for grabs. Joining the chorus of concerns was the Greater Santa Barbara Restaurant and Lodging Association, as well as an activist with the West Beach Neighborhood Association.

Fell observed that when Rosenfeld’s $2-billion Century Plaza project went before the Los Angeles City Council, not one councilmember voted against it, and not one member of the public testified against it. “That’s the kind of guy he is,” Fell said. But whether Rosenfeld has sufficiently mastered the art of compromise to make it through Santa Barbara’s daunting review process has yet to be seen.