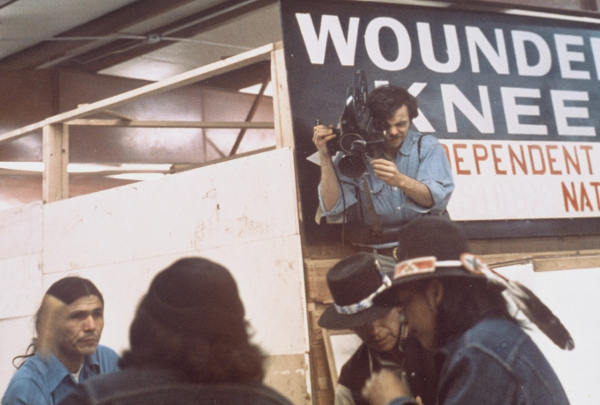

What I Learned at Wounded Knee

Death, Defiance, and Defining Moments

For reporters who want to get inside a foreign culture to make a story resonate with readers, listeners, or viewers back home, language and race are challenges. Until 1973, when I covered the Indian occupation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, I had never seen anyone shot to death, much less been on an Indian reservation. Then I met Frank Clearwater, a 47-year-old Cherokee from North Carolina. Clearwater and his wife wanted so badly to be part of the uprising that they’d hitchhiked from the East Coast to South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. By the time they arrived, the famous village was surrounded by hundreds of FBI agents and U.S. Marshals, and federal negotiators had vowed publicly to “starve out” the Indians. After a long hike through the reservation backcountry, the Clearwaters managed to penetrate the government cordon. I bumped into them outside the trading post. It was a cold night, and I told them where they could find some blankets.

Clearwater returned with the blankets and lit up a “ready-made” cigarette he’d bought in a store. It struck me right away that I hadn’t seen a store in nearly two months. He offered to share it with me and several Indians who were standing around. The occupiers had long ago run out of tobacco, and some people had resorted to smoking shavings from cherry bark. A store-bought cigarette was something special, and everyone gathered around. We passed the cigarette around in a circle, like a form of communion, until a long red ash could be seen in the dark. Then the newcomers walked up the hill to the little pine church to look for a place to sleep.

The next morning, just after dawn, a small plane rented by Wounded Knee sympathizers flew over the FBI bunkers and parachuted bundles of food to the besieged compound. The dramatic airdrop ignited a hellacious firefight between the Feds and the Indians, rousting Frank Clearwater from the floor of the church. As he sat up in his blanket roll, a bullet ripped through a thin wooden wall and blew off the back of his head. By the time I got there, Indians were crouched at the windows with their rifles. Bullet holes marked the walls, and blond-colored splinters of pine lay on the floor.

Clearwater was already dead. A blanket I’d given him had been used to roll him onto a makeshift stretcher. I crouched down for a moment, thinking. This was the man I’d smoked the same cigarette with a few hours earlier. Now his face was frozen, his lips contorted, and the blanket was covered with blood and tissue. I couldn’t help thinking: Wasn’t I just talking to you about how cold it was?

The next to die was a Lakota Sioux named Buddy LaMonte, a Vietnam veteran just home from the war. He was hit when he popped out of a foxhole with his rifle about 50 yards from the trailer where I’d slept the night before. A federal agent killed him from a distance, probably using a longrange sniper scope.

Buddy was popular on the reservation, and his mother, Agnes, worked as a cook for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The local ties earned the LaMonte family the right to bury him in the historic Wounded Knee cemetery, next to the victims of the 1890 massacre. Before the burial, the casket was opened and the mourners filed by to pay their respects. At the grave site, Agnes talked about her great aunt, who was killed at Wounded Knee in 1890, and how Buddy had gone to overseas “to fight communism.” When he got home, she said, his fight was with the powers that ran the BIA like a prison camp.

Buddy’s casket was full of gifts for the trip to the spirit world: food, chewing gum, and a package of Lucky Strike cigarettes. Indians are proud when a young man leaves the reservation to serve his country, and Buddy was dressed in the same army uniform he’d worn when he left home for Vietnam. But his hair was long now, below the shoulders of the uniform, and he was wearing beaded moccasins, not military boots, for his trip to the spirit world. Someone had placed a package of razor blades and a can of Gillette shaving cream on the front of his olive green uniform, by the medals he’d earned defending his country.

Relatives snapped photos with Instamatics.

Buddy’s grief-stricken sister had come from Denver for the funeral. I had been taking pictures for two months, but as I raised my camera to photograph Buddy, she stopped me and asked sarcastically, “How much money will you make on this story?”

“What do you mean?” I stammered, defensively.

“Getting pictures of my dead brother,” she said. “I know you reporters. All this is just a job for you.”

In the flash of an eye, my right to be in Wounded Knee was filled with doubt. Suddenly, I was a non-Indian, a waiciscu or “a taker of the fat” in Lakota. Here I was at an Indian mass grave, a piece of ground heavy with race and history. I was young, and her remark impaled me like a rod through the chest. I was a photographer. I thought I had a clean heart. But I put the camera down. As visitors who’d had no part in the long siege clicked away, I would have to remember the day without film.

As I surveyed the mass grave in front of me, I tried to imagine what the 1890 massacre might have looked like through my viewfinder. In my mind’s eye, I saw the archival images from Life magazine, the old picture of the 7th Cavalry dumping bodies into the rectangular pit. I thought of all the skeletons — some 300 — in the ground underneath. By now they had been in this pit for 83 years. I thought of the soldiers, members of General Custer’s old unit, who had gotten Medals of Honor for what they had done, and how the Pentagon still refused to recall the awards. I thought about killing and the clash of civilizations that had taken place under my feet. I thought about how war distorts the truth and how history fights to correct it. Then I wondered about the role of journalism. And what lay ahead for me.

It seemed to me that reporting at its simplest was remembering what you saw on the other side of the mountain and faithfully recounting it for people who couldn’t make the trip. If I was going to keep doing this work, I had to find a way to strengthen my purpose, not to flinch when I got close to what was real.

I needed to find a “low road” to travel on, away from official truths, a path to witness events up close, a way to demystify a “foreign” story. Most of all, I needed to honor the work I was choosing. The next time, I vowed, I would get the picture and not put the camera down.

Kevin McKiernan has reported on crises in El Salvador, Iraq, Burma (Myanmar), Syria, and other places around the world over the course of his career, as well as producing audio documentaries on Wounded Knee for NPR in 1973 and 1974. Now, with cinematographer Haskell Wexler, McKiernan is working on a film about the events in 1973 at Wounded Knee.