Assessing the Channel After the Refugio Oil Spill

Santa Barbara Channelkeeper Monitors Sensitive Marine Habitats

There I was all alone bobbing amidst a kelp forest off the Gaviota coast on the RV Channelkeeper, playing photographic whack-a-mole with a harbor seal that would periodically pop his head above the water to say hello before once again sliding beneath the serene surface of the Pacific Ocean.

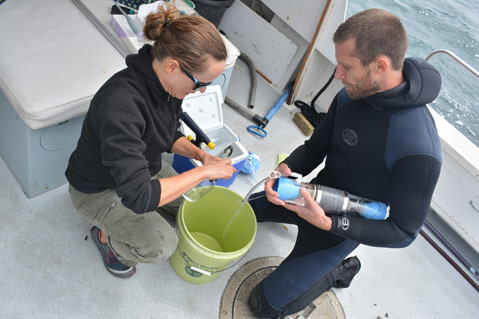

My guides on this excursion were Ben Pitterle and Penny Owens of the nonprofit Santa Barbara Channelkeeper. Among their tasks this past Thursday were taking plankton samples for the state Department of Public Health, monitoring recreational use of the channel, reporting prohibited fishing of protected areas, and grabbing a water sample from a pH testing station installed by a UCSB research group.

Their primary task, however, was to do reconnaissance at the Naples Marine Protected Area, where they rolled off the back of the boat in SCUBA gear, and left me to my lonesome — and my new marine mammal friend. The Naples coast, despite a parade of development plans since 1888, has remained largely pristine due to equal doses of luck and resistance from the county and environmental groups.

The latest potential assault on this biologically diverse region, however, is the estimated 20,000 gallons of oil that spewed into the ocean from a busted pipeline adjacent to Refugio State Beach on May 19. This is of special concern to Channelkeeper because they have been promoting ecotourism in the area, even subsiding diving trips chartered by area businesses.

“If you want to protect a place, the best way is to promote community stewardship,” explained Pitterle. Aside from sharing the beauty of the region, ecotourism also presents an economic benefit of preserving Naples’s rich ecology.

While the Channel Islands are the premier diving destination in the Santa Barbara Channel, there are plenty of other rewarding underwater vistas to explore nearby. Naples is “our little coastal gem,” said Owens. Indeed when she and Pitterle climbed back onto the boat, they couldn’t stop gushing about what they’d discovered — a towering underwater shelf inhabited by sheephead, lobster, kelp bass, rock fish, half moons, and seals. “That was bitchin’!” exclaimed Owens. “Top one or two epic dives ever,” said Pitterle.

Although the two had seen a dying sea lion floating in the same area just a week before, there were no evident signs of oil damage this past Thursday. Likewise, although the water was heavy with oil slicks, they were not of a volume that was unseen before the spill. Slicks are quite common in the Channel, a thoroughfare rife with boat traffic, drilling platforms, and natural seeps.

After the gut punch of crude that overwhelmed sea creatures and subsequent cleanup efforts, remnants of the spill have reached a point where their effects will play out over a scale of time and space undetectable by the human eye. For instance, they may kill off plankton that provide the initial link in entire food chains, an impact that could possibly take years to manifest.

That’s the rub for organizations like Channelkeeper whose mission it is to protect coastal ecosystems, but who also want to share those ecosystems with a wider public. It’s a challenge that will be faced by the tourism and fishing industries as well.

“If a closure is unnecessary, it’s our duty to let people know,” said Pitterle. “It’s just that we don’t want to do it in a way that makes people think everything’s okay. It’s a fine line.”