Whose Pope? Whose Church?

Pope Spotlighted Dorothy Day, Cofounder of Catholic Worker

Pope Francis’s address to Congress was remarkable in surprising ways and especially relevant for the Santa Maria Valley in northern Santa Barbara County. The Pope made examples of four historical figures (“great Americans”) in calling for a more egalitarian and compassionate American society. Only one was a woman, but think about the woman the Pope chose.

First, consider one woman the Pope might have spoken about, but didn’t: Elizabeth Ann Seton. She was the first U.S.-born person to be canonized a saint by the Catholic Church. This year is the 40th anniversary of her canonization. Seton was a devoted spouse and then a young widowed mother of five children. She was also an educator who founded the Sisters of Charity — the first women’s religious order started in the United States. The Sisters of Charity have played an important role in education and health care in our country. They are famous for their compassionate service as nurses to wounded soldiers of the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War.

The Pope had a ringer and sure bet in spotlighting Seton. A great wife, mother, church woman, and citizen.

But, instead, Pope Francis spotlighted Dorothy Day, the cofounder of the Catholic Worker movement. I was ecstatic when I heard it, because I am closely associated with a Catholic Worker house (in Guadalupe). And I was also stunned.

Dorothy Day had an abortion and a child outside of marriage, and she was divorced. She was a suffragette, socialist agitator, and pacifist. She supported draft resisters during World War II and the unionization of migrant farm workers and other laborers. She was arrested many times for civil disobedience. In no uncertain terms, she condemned America’s capitalism and militarism. But she was also a devout Catholic who staunchly supported church doctrine, and she reached out to the homeless, hungry, and disenfranchised, and she led many others to do so.

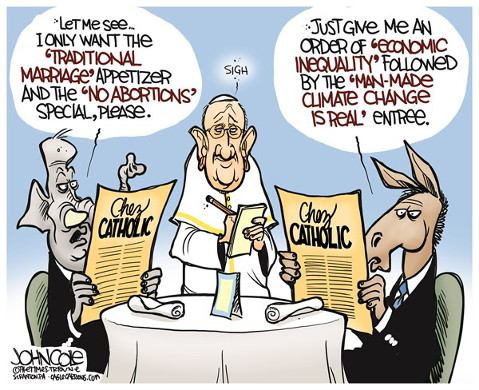

It was equally remarkable to see the Pope give his speech with two prominent Catholic men sitting behind him as backdrop: Vice President Joe Biden, who supports same-sex marriage (which the Pope opposes), and then-House Speaker John Boehner, who calls for a reduction in welfare and a much-less-restrained market economy (which the Pope explicitly criticizes).

In his speech, Pope Francis unequivocally argued that the true measures of a good society are how a country treats its poor, its vulnerable, and its immigrants. The Pope implied that we Americans fall far short on such measures.

As a Catholic activist, I am often at odds with people in the Santa Maria Valley. The economy at our end of the county revolves around large commercial farms (which mostly grow hand-picked vegetables and strawberries) and Vandenberg Air Force Base (where intercontinental missiles are tested, and nuclear missile operators are trained).

Many of the people I encounter in my protest are other Catholics who support big agriculture (which I believe exploits immigrant workers), American military aggression, including the maintenance of nuclear and spaced-base weapons (which I believe make the world unsafe), and vigorous deportation of undocumented residents (which I believe tears at the fabric of our community). So I found much solace in the Pope’s speech.

But then I had second thoughts, seeing the image of Biden and Boehner looking like awkward bookends on either side of the Pope. And I realized that for all his critical discourse during his visit to the United States, the Pope had condemned no one. There was an uncomfortable and sobering message for me in the Pope’s words and manner.

The message was this: I have no more claim on the Pope, or the Catholic Church, or the Gospel, than the people whom I strongly oppose on social and political issues. And I must acknowledge that those I challenge may be better persons in many ways than I am.

And to build that better society the Pope envisions, I and those who stand on my side of the issues and join in organizing, protesting, and sometimes civil disobedience must ultimately find productive ways to come and work together with those on the other side.

While those of us on the differing sides may feel compelled to passionately pursue what we believe to be just and true, we must never lose sight of the dignity and value of those who stand against us — even when they have more power and wield it in harmful ways. Perhaps what really makes great Americans in our modern, sociopolitical context, is the willingness to resolve differences with civility and respect.