What If There Wasn’t a Cachuma?

We'd Be All Wet Without a Dam

NO SPILL? As drought-threatened Santa Barbara County folks pray for Cachuma to spill, imagine what life would be without it.

Miles of Goleta tract houses might not exist, nor even UCSB, or much more that we take for granted.

Back in the late 1940s, with the City of Santa Barbara imposing rationing, the fiercest political battle in county history raged: Whether to approve what opponents dubbed “that damn dam.”

Opponents, led by the owner of many acres around the Santa Ynez Valley site, Lewis Welch, who wanted to develop it, hurled angry shells at the federal project:

It was a “socialist” New Deal boondoggle. The lake would never fill, and the dam would never spill. It was a government grab to control local water. It was impossibly, outrageously expensive. It was a theft of Santa Ynez and Lompoc Valley water (echoes of which are still heard).

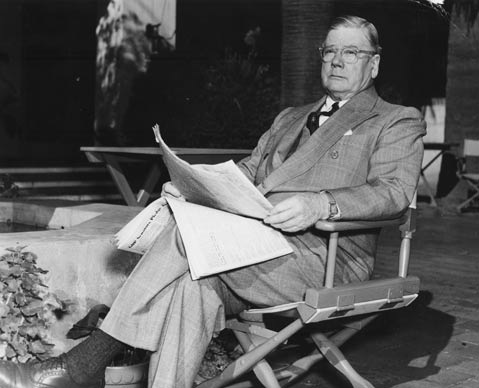

But proponents had a mighty champion on their side, one with powerful connections in Washington, D.C.: T.M. Storke, owner and publisher of the Santa Barbara News-Press. T.M., arguably more powerful than any mayor or county supervisor, had long held a paternalist view of Santa Barbara’s destiny.

Thanks to his Washington connections, he was able to bring Depression-era projects and jobs to Santa Barbara. It helped that he was a Democrat during the Franklin D. Roosevelt years.

In 1938, the governor appointed him to fill out the unexpired term of his ailing friend, U.S. Senator William McAdoo, a brief but potent political sword. It could be argued that without the power of his press and his friendships among county supervisors and in Congress, the fight for Cachuma might have been lost.

Welch “resorted to every trick known to politics … ” Storke wrote in his 1958 memoir, California Editor.

After a long, vicious campaign, a vote was held on November 22, 1949, on the $43 million project, involving all the water agencies aiming to get hookups. A simple majority in favor wouldn’t be enough.

It would take an overwhelming vote to convince budget makers back in Washington.

The vote in favor was overwhelming, and the project was green-lighted in Washington. Ground was broken in August 1950, and not a moment too soon. Water for entire communities, including Isla Vista and the Ocean Terrace area, had to be brought in by barrels or even buckets. Clearly, something had to be done, fast.

For years, growth had slowed dramatically, but in the late 1950s the South Coast began experiencing a strong wave of growth. Young families riding the tide of postwar prosperity were moving in.

Meanwhile, the drought went on. Maybe the naysayers were right. Maybe it was the wrong dam in the wrong place, a semi-arid desert corner of Southern California. Finally, the wait was over. Santa Barbara County was hit by powerful rainstorms and even floods.

On April 12, 1958, at 3:32:12 in the afternoon, water emerged, flowing over the dam. A chorus of shotguns blasted out the good news, sirens went off, and Storke, 81, proudly posed holding a large clock with its hands pointing to the historic moment.

Today, we await a latter-day spill, but we’re armed with confidence that the not-so-damned dam will spill life-giving H2O to hundreds of thousands of people who probably wouldn’t be here without Cachuma.

Cachuma water, piped through the Santa Ynez range of mountains, led to a building boom in Goleta as the 1960s dawned. Lemon orchards were bulldozed, replaced by tract houses. Landowners harvested dollars instead of citrus.

When I bought a brand-new Goleta home in 1960 and planted a lawn, a volunteer lemon tree sprouted. Goleta started building a school a year.

Isla Vista, responding to fast-building UCSB, became what people called “a student ghetto” of apartment buildings, along with the resulting problems of too many people jammed together and too little local government.

UCSB, located there with the help of — who else? T.M. Storke — became a cultural and educational boon to the community. My wife earned her teaching credential there, and three of my children went on to get degrees.

Storke, respected by many but hated by some, is gone, but not a man to be forgotten