Profiles in Design: Lockwood de Forest III

Landscape Architect Dramatically Changed Face of Santa Barbara’s Outdoor Spaces

The name of landscape architect Lockwood de Forest III is synonymous with the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, which turned 90 this year. But he is also a pioneer of what’s suddenly on the forefront of California’s drought-fried frontal lobe: water-wise gardens. According to his son, Kellam, who is 89 years old and still lives in Santa Barbara, de Forest raged against lawns back in the 1920s and used the Botanic Garden to primarily showcase for native, more drought-tolerant species.

Today, after many decades in exile in the Bay Area, de Forest’s archives now reside at UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum (AD&A). It’s a great place to realize that, along with his innovative Botanic Garden plantings, the landscape architect laid the groundwork for the horticulture design elements that can be found throughout Santa Barbara.

De Forest was born the son of New York artist and furniture designer Lockwood de Forest II, who had relocated to Santa Barbara for the last 17 years of his life. Although the elder artist appeared to be colorful and eccentric (among his collection of friends: Rudyard Kipling’s dad), “my father fit that description better,” said Kellam.

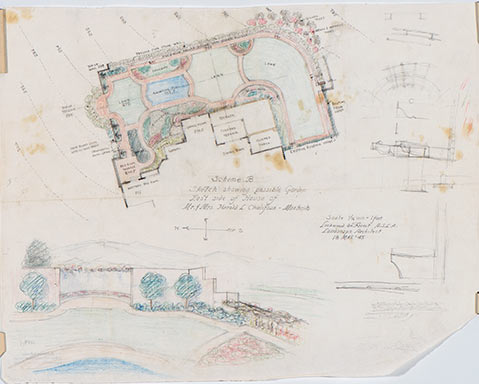

De Forest III studied landscape architecture at Harvard University and UC Berkeley before opening his Santa Barbara office in 1920, immediately taking on a batch of estate garden assignments, including Arthur Meeker’s Constantia and George Steedman’s Casa del Herrero.

In December 1925, Lockwood and his wife, Elizabeth, founded the Santa Barbara Gardener, a periodical they produced through 1942. Many historical passages paint the portrait of Elizabeth Kellam de Forest as her husband’s professional equal.

“That’s a little overstated,” Kellam said. “My mother supported my father completely. She never went to the office. She did the principle writing for the publication.”

De Forest designed and completed his Mission Canyon family home by 1926, which is the same year Kellam was born. The Roman-style house on 2659 Todos Santos Lane — with its central atrium, five fireplaces, outdoor rooms, tiles from Damascus and India, and a lush, prefacing garden of native plants, sandstone, and browning Kikuyu grass — sits on 0.76 acres with only abstract references to Santa Barbara’s Mediterranean fixation. De Forest also worked on the adjacent William Wurster–designed home of his father-in-law and Botanic Garden bureaucrat Frederick Kellam, planting olive trees and pineapple guava hedges in gray (echoing the mountain color) in their shared driveway.

Except for two years serving during World War II, de Forest worked on myriad Botanic Garden projects until 1949, when, at a relatively young 53, he died of pneumonia. “He was pleased with the way it was going,” Kellam said of his father’s Botanic work, “but he died before he was completed.”

Decades later, UCSB’s AD&A Museum began as an extension of the collection of an equally forward-thinking man, founder David Gebhard, who was actively collecting in the 1950s and ’60s. Today, curator Jocelyn Gibbs, who started at the museum in 2010, has helped rebrand of the institution, which now offers concerts, readings, a vibrant lecture series (Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne spoke recently), even knitting sessions, and, of course, yearlong exhibitions. Opening June 25 are the following exhibits: Sub Rosa: Behind the Scenes at the Museum, Computation & Expression: Projects from the Media Arts and Technology Program and The Art of Illusion: The Carlos Diniz Archive.

As Gibbs explained, the de Forest collection of architectural drawings, personal effects, and ephemera —including 5,000 drawings from his major works — went to UC Berkeley in the 1950s. But it finally returned to UCSB, thanks to a gentleman’s agreement of sorts between the two universities to maintain regionally correct archives: Berkeley holds the works of Northern California architects, while UCSB houses Southern California’s.

“We always felt that the collection should come back,” said Gibbs, standing next to a cart overloaded with troves of de Forest’s correspondence, including an album he assembled for client Wright Ludington with highlights from their voyage to Italy and Spain in 1922 as an exploratory research trip for Ludington’s Val Verde estate in Montecito. Bonded by their shared passion for California landscape, the pair had met as boys at Ojai Valley’s The Thacher School.

De Forest’s letters predate the birth of Kellam, who for years worked in Hollywood running a research service for motion picture and television production until his 1991 retirement. Today, the octogenarian resides at a senior-assistance complex near where he grew up. A younger brother, Lockwood IV, lives in Australia.

Kellam has only fond memories of their childhood. “It was a wonderful time,” said Kellam, whose parents worked hard but never at the expense of raising their boys. “There was family time, especially on the weekends. Fairly often, we went to the Botanic Garden.” Though he’s seen a lot of building and fears that “the developers keep trying to erase” Santa Barbara’s charm, Kellam still loves the area, perhaps because his father’s imprimatur can still be felt ubiquitously around town.

As for that storied Todos Santos Lane family home, it’s for sale, listed by Sotheby’s at $3,295,000. Eventually, a new owner will purchase the property and, along with it, the inherent history and legacy symbolizing the very foundation of enchanting Santa Barbara.