Trump Effect: The Surge to Citizenship

Immigration Crackdown Drives Many Santa Barbarans to Become Americans

Josefina Valdez and her late husband emigrated to the Santa Ynez Valley from Mexico in the 1980s, and for more than two decades, they worked hard and raised two sons, relying on the “green cards” that allowed them to live and work here legally. They never gave citizenship a second thought — until Donald Trump was elected president. Then the couple raced to get their applications in.

“When these elections began, there were many changes in people’s behavior, and they started showing more racism toward Hispanics,” Josefina Valdez said, recalling the anti-immigrant rhetoric of the election campaign and beyond. “They gave you ugly stares on the street and in the stores or when you picked up your kids at school. We had not experienced that before, so much.”

Valdez, a 45-year-old domestic worker, personally rounded up her friends to make up the quota for a citizenship class offered by Allan Hancock College at Santa Ynez Valley Union High School.

“We Hispanics do not want another Trump presidency,” Valdez said. “A misdemeanor, a traffic violation — any small thing, you could be deported. I told my friends, ‘Come on; we need you; get with it!’”

On September 20, Valdez was among 5,000 immigrants at the Los Angeles Convention Center who raised their right hands and proudly took the naturalization oath of allegiance to the United States.

Across the country, applications for citizenship have increased nearly 36 percent since 2015, according to a recent report by the National Partnership for New Americans, a coalition of 37 immigrants’ rights groups. In California, applications have spiked by 47 percent in the past two years.

Between October 1, 2016, and September 30, 2017, alone, the report shows, more than one million U.S. residents with green cards applied to become citizens, a 10 percent increase over the previous 12 months.

“Some people have it circled in red on their calendar, the minute they can apply,” said James Thomas Daly, a Santa Barbara immigration attorney. For most immigrants, that’s after a minimum of five years as legal permanent residents.

Importa, a nonprofit group that provides free legal services for immigrants in Santa Barbara, Santa Maria, and Lompoc, has submitted 500 applications for citizenship this year to date, twice as many as last year, organizers said. Guadalupe Pérez, a North County immigration specialist for Importa, said Trump’s “aggressive policies aimed at families and children” were fueling the numbers.

Importa has been awarded a state grant to help immigrants apply for green cards and citizenship, providing everything from photographs to translations of supporting documents. Many clients are surprised to discover that they qualify for a waiver of the $725 federal fee for the citizenship application if they receive food stamps, receive MediCal health insurance, or have retired on Social Security benefits, Pérez said.

“We are seeing a lot of older people apply who have been living here with green cards for a long time, even 40 years,” she said. “And we didn’t used to see so many young people coming in right out of high school or college. They never had much interest in voting; it didn’t affect them as directly as it does now.”

Enrollment in citizenship classes that help applicants study for the civics test has increased by dozens of students at both Allan Hancock and Santa Barbara City College this year, school officials said. Hancock added a class in Lompoc last year, for a total of six in North County. In addition, attendance has tripled at a weekly citizenship class in Santa Barbara run by Immigrant Hope, a faith-based nonprofit group.

An estimated 8.8 million immigrants who are lawfully in the U.S. are eligible to become citizens, according to the National Partnership report. There are no recent figures for Santa Barbara County, but a 2010 report by the California Immigrant Policy Center estimated that about 33,000 residents here were eligible to become citizens by 2015. If they all registered to vote, the rolls would increase by 15 percent.

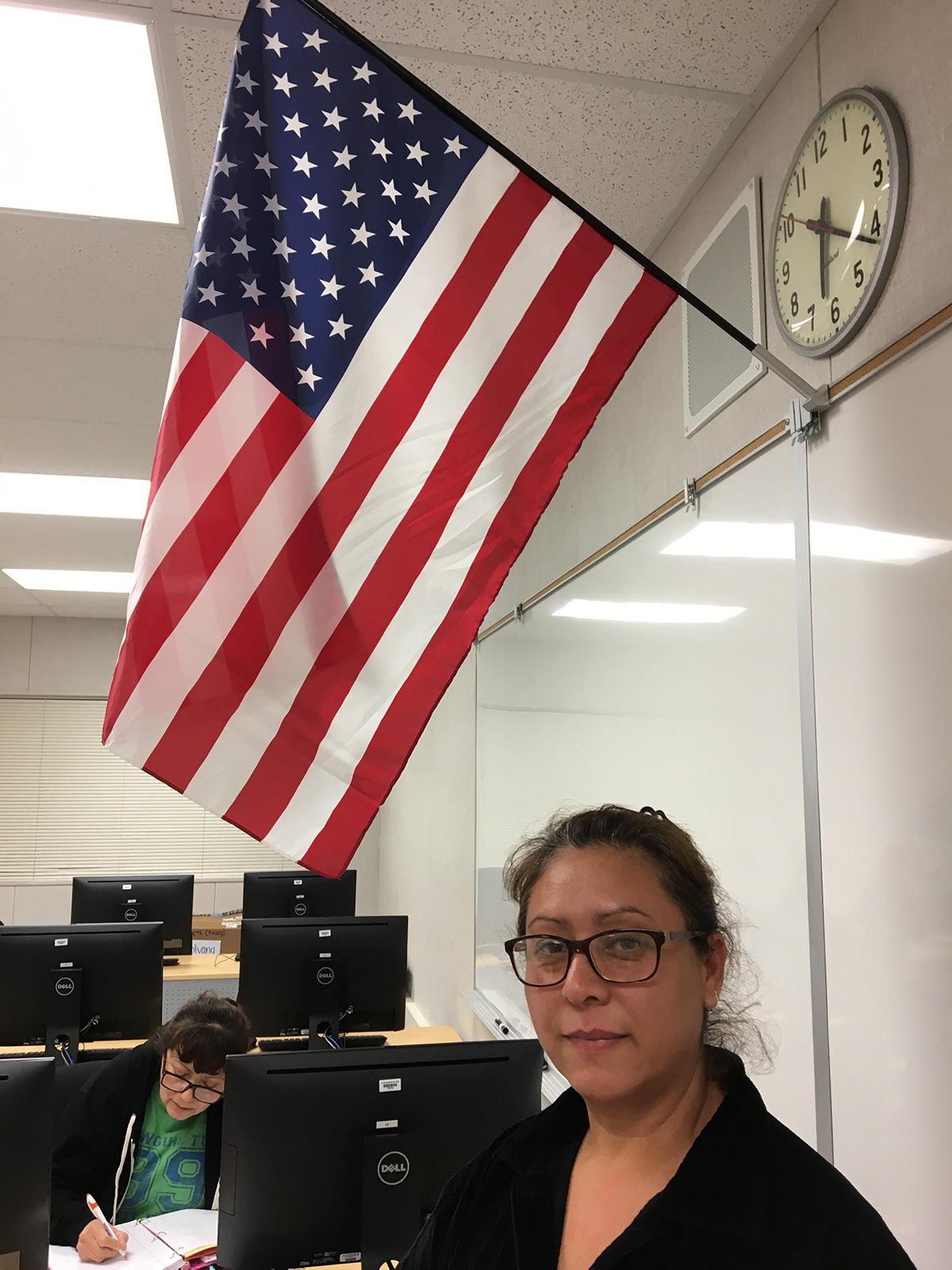

One newly registered voter is Alexa Cervantes, a 27-year-old artist and City College student from Mexico who became an American citizen in October. Cervantes cast her first ballot for Cathy Murillo as mayor in the recent Santa Barbara municipal election.

“President Trump says many very ugly things about us,” Cervantes said. “I was really afraid of losing my green card if I left the country to visit my mom.”

Green-card holders can’t vote or obtain U.S. passports, and they can be deported for fraud or serious felonies, or for catch-all “crimes of moral turpitude.” Every time green-card holders leave the U.S., their reentry is at the discretion of a border officer. If they leave for too long — typically, six months or more — they risk losing their green cards on grounds of “abandonment.”

Since Trump took office in January, he has moved to dismantle protections for undocumented immigrants who came here as children before mid-2007 (the DACA program, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), and he continues to push for an extension of the border wall between Mexico and the United States. Trump has restricted entry to the U.S. to travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries and Venezuela. He has plunged hundreds of thousands of Central Americans into legal limbo by rescinding their protected status here.

“It’s threatening, because you never know what’s next,” said Brie Ehret Barron, 57, a German spiritual facilitator who is taking a citizenship class offered by City College at Santa Barbara High School. Barron said that both her mother and sister have cancer and live in Europe, and that if she was needed there, she couldn’t easily visit.

“It is quite a hassle with a green card,” Barron said.

Because of the burgeoning number of applications, would-be citizens must now wait twice as long for their paperwork to be processed as they did in 2015, the National Partnership report shows. It’s a delay that the organization likens to “building a second wall.”

As of late September, the waiting period for new applicants at the San Fernando Valley field office of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which covers both Santa Barbara and Santa Maria, was about eight months, government data show. A USCIS spokesperson said the agency was allocating additional employee overtime and recruiting new hires to reduce the wait.

One evening in Barron’s citizenship class last week, Juan Aguilera, 67, an electronics assembler in Goleta, and his wife, María del Rosario Aguayo, 62, a former office cleaner, had some exciting news. Neither speaks fluent English, but earlier that day, after more than 25 years working in the U.S., and after attending citizenship classes every night from Monday through Friday for the past two years, both had passed the oral interview and civics test — in English — by a USCIS officer in Los Angeles.

“I kept my eyes glued to his mouth,” Aguayo said in Spanish, mimicking an exaggerated stare as her classmates giggled. Aguilera said he forgot his wife’s birthdate; he was so nervous.

What questions did the officer ask them? The class wanted to know. The couple remembered these: Who was the first president of the U.S.? What is the name of the Chief Justice? Who fought in World War I? Why are there 13 stripes in the American flag? Who was president during World War II? What is the supreme law of the land?

Aguilera and Aguayo are now awaiting the date for their swearing-in in Los Angeles. The city hosts the largest naturalization ceremonies in the country, and the couple plan to invite their five children and 15 grandchildren to come along.

“We’re going to be able to vote against Trump now, that’s for sure,” Aguilera said. “He’s separating families.”