Montecito Mudslide Evacuation Orders, Emergency Alerts Explained

Sheriff Brown, EOC Director Lewin Give Insight into Santa Barbara County Disaster Operations

At 10 at night the Monday before the storm, Rob Lewin told his people at the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) to grab a cot and get some sleep, or go home if it was nearby, but be ready to work in four hours’ time. He and his staff had warned Montecito and Carpinteria of the pending rains at a press conference the Friday before and sent alerts to 21,000-40,000 contacts by every means possible — save snail mail — since then. They’d put in the direst terms that serious floods — both mud and water — were threatened from the rainstorm headed for Santa Barbara’s south coast early Tuesday morning. Now they had to wait for it to arrive.

Out in Montecito, a swift water rescue squad and urban search and rescue teams were standing by. Six inmate crews had spent the day clearing creek beds, following up on three weeks of debris basin clearing by county Public Works. High-clearance military trucks had arrived. More support had been requested from the state in advance of the storm, unheard of among California emergency planners.

Sheriff’s deputies had spent the day banging on doors, informing people of the coming floods and the mandatory evacuation order in place above State Route 192. Of the 1,400 contacted, 200 said they’d leave. Most in Montecito were weary from almost two weeks of Thomas Fire evacuations, and gentle sprinkles of rain gave the lie to what they were being told. Many stocked up on sandbags.

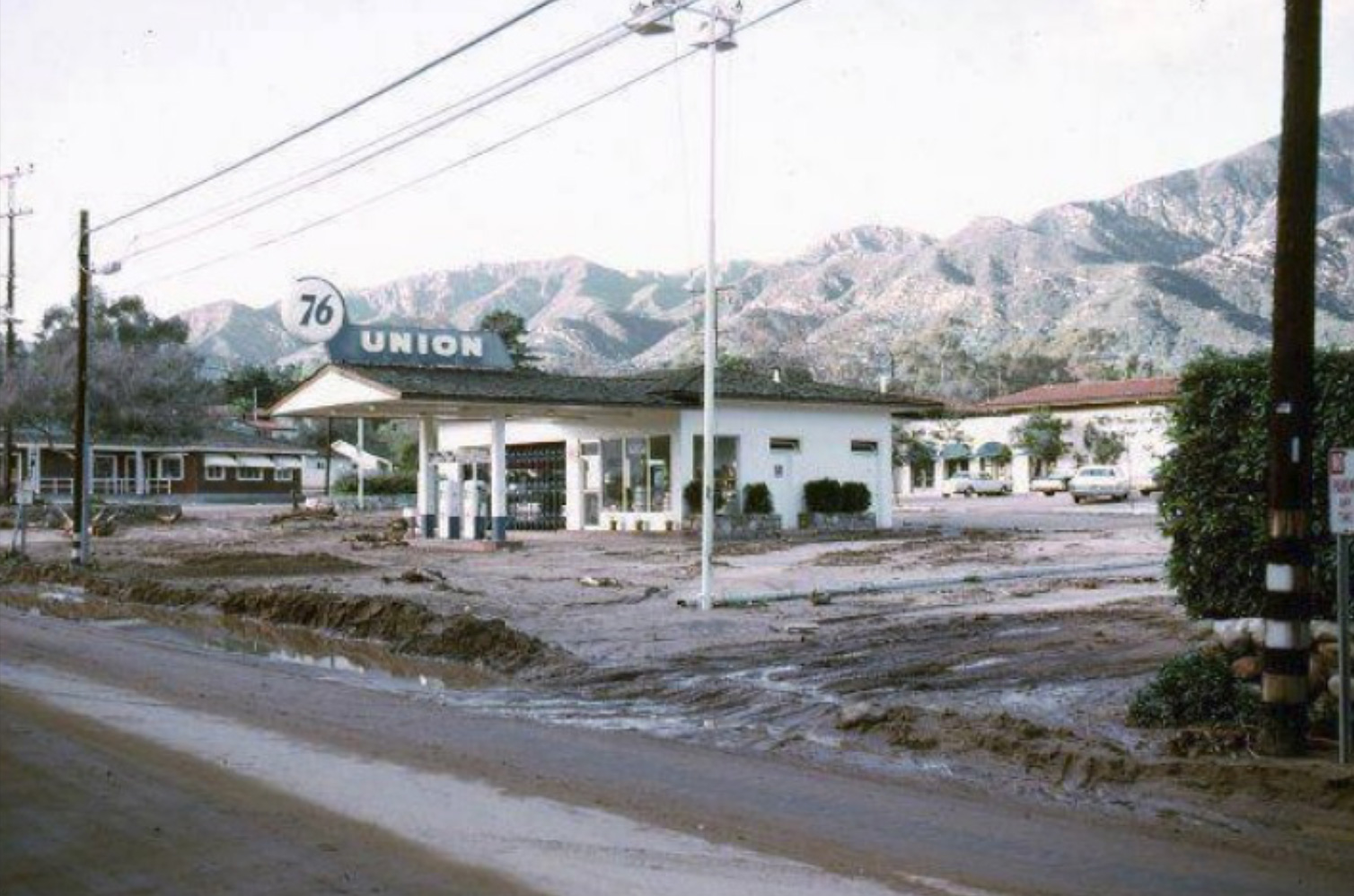

“In our minds, we were geared up,” Lewin said. “We’d been trying since Friday to say the creeks that are normally dry are going to turn into raging rivers of trees and rocks. Roads are going to be taken out.” Lewin, formerly the Cal Fire chief in San Luis Obispo, had been reading up on floods from Montecito’s past, including in the winter after 1964’s Coyote Fire. He knew flooding and mudflows were possible all the way down to Coast Village Road and the highway.

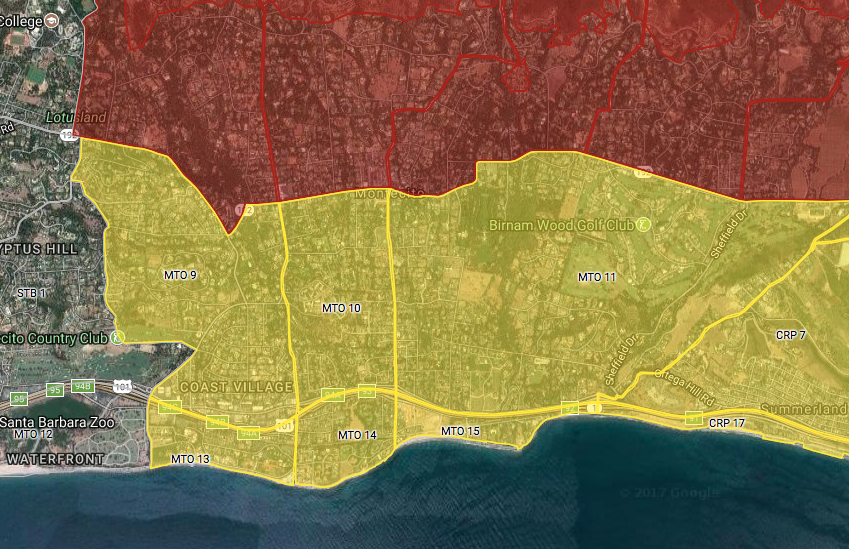

That Sunday, a summit had gathered at the EOC to make a decision on the evacuation borders. Technical advisors gave the worst-case scenario: a heavy rainstorm of up to an inch per hour, maybe as much as four inches total. With the hillsides scoured of vegetation by the Thomas Fire, the flood risk was 10 times greater. But historically, even during the rain-soaked year of 1969 — which had no fire, Lewin acknowledged — the dangerous rock and mudflows had stayed in the higher elevations above the 192. The mandatory evacuation zone was set north of there.

Sheriff Bill Brown accepts the responsibility for placing the mandatory evacuation line at the 192, though he was not in the room, Undersheriff Barney Melekian there in his stead. “The 192 is the only straight east-west arterial that there was,” Brown said. “Everything else was a winding spaghetti of neighborhood streets.” Indeed, through Montecito, even the 192 is known in stretches as Foothill Road, Mountain Drive, Mission Ridge Road, Stanwood Drive, Sycamore Canyon Road, East Valley Road, and Toro Canyon Road before becoming Foothill Road again as it heads into Carpinteria.

The evacuation zones used, said Brown, had been developed after the Jesusita Fire when it became obvious that the Sheriff’s Office needed to have a fast way to select evac areas and identify the intersections needed to keep them closed.

“The storm that was predicted, and that we were prepared for, was not the storm we got,” Bill Brown said. The rain intensity was not only unprecedented in Santa Barbara, it had not previously been known in all of California history, he said. “Eighty-six hundredths of an inch fell in 15 minutes,” he exclaimed.

“The storm predicted and that we took actions for is what happened in Carpinteria,” Lewin said. “It’s got the same steep slopes, the same steep canyons. They had a mess in Carpinteria, mud and some flooding.” Specifically, it had no intense rainfall or loss of life. Montecito’s historic storms had nowhere near the violence of this one, he said.

Within hours before the storm, as much as nine inches total in the hills was forecast. What Montecito got was about 3.3 inches. But of that, a half-inch downpour fell within five minutes, letting loose the dirt and setting boulders to bound down-canyon, roiling the creeks out of their beds. According to county rainfall intensity records, it was a once-in-200-years event.

A video put together by County Fire show the storm cell moving onshore and pounding Montecito from Hot Springs Canyon to Romero Canyon before dissipating. The extraordinary mass of water, mud, boulders, and trees swept beyond the 192, and 20 people are known to have died so far.

A flash flood is just that, a rush of water that happens instantly. Although the weather radar can see such a cloudburst form, emergency managers have very little time to issue a warning. The National Weather Service let the EOC know sometime after 1 a.m. on Tuesday that it was sending out a flash flood warning, Lewin recalled, the highest level of notification. Trouble was, the text alert did not get to Lewin’s phone or anyone else’s at the EOC who had Verizon as their carrier. Worried, the EOC composed and sent its own message through multiple channels — text, email, Reverse 9-1-1, and social media — at 2:46 a.m. to Thomas and Whittier burn areas, at 3:07 a.m. to the Alamo Fire area, and a WEA at 3:51 a.m. The phone system couldn’t handle the onslaught of the thousands of calls; they took about an hour to all be dialed.

“All the systems have limits,” Lewin said, wearily. “An email can say everything. Nixle is 138 characters.” And the emergency center’s version of Twitter is the older 140-character one. “We struggle so hard to put together meaningful message in 90 characters,” Lewin continued, speaking of the federal Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system. “‘East of here, west of there.’ No one knows what’s east or west here. And ‘evacuation’ is a long word.” The WEA (pronounced WE-ah) system plagues Lewin. “How would you feel in Santa Maria if you got an evacuation text to get to higher ground?” he asked rhetorically. It’s like playing Scrabble with the March Hare.

About the only bright spot in the urgency of getting out the alerts was that the Emergency Alert System (EAS) worked, a system Lewin’s been trying to fix for some time. “I was watching KEYT,” said Lewin, “and the emergency banner showed up correctly.” Previously, an alert would switch a Cox Cable viewer’s channel to C-SPAN. It also would fail to display the banner.

Lewin, who said Christmas Day is the only day he’s not worked since the Thomas Fire started on December 4, clearly loves the challenge. His team has succeeded in getting authorization from the feds, he noted, pleased, to fund high resolution mapping for the new land contours in Montecito. They were going to get ready for the next big one.

Editor’s Note: This story was changed on January 16 to correct Sheriff Brown’s statement regarding the storm prediction, and also to add that Lewin was aware of the mudflow extent from past floods.