Antioch Santa Barbara Founder Recalls University’s Humble Beginnings

The Small College That Could

It’s more than 40 years since I was hired to establish an Antioch University campus in Santa Barbara. It wasn’t easy, but it was a fulfilling professional journey lasting from 1977 to 1988. Arriving in Santa Barbara after founding a center for returning women students at UMass/Amherst, I was initially frustrated by the lack of comparable job options here. I was also shocked by the conservative nature of the Santa Barbara community at that time. For example, in 1972 the dean of the SBCC Adult Education Division told me there wasn’t a perceived need for additional programs for women because they already offered “Fascinating Womanhood” courses on How To Strengthen Your Marriage and Enrich Your Life.

The late Marya Weinstock, a UCSB psychologist, was the first to tell me about the Antioch position, saying, “Apply for this job, and stop kvetching!” I did and was hired by the provost of Antioch West, a constellation of five larger West Coast campuses. The other executive directors, all men, taught me how things worked in a system with satellite campuses and a complicated governance system based in Ohio.

Antioch College started in 1853, led by its visionary founder and abolitionist Horace Mann. It was one of the first nonsectarian educational institutions in the U.S., and the nation’s first co-educational college to offer the same opportunities to both men and women, to appoint a woman to its faculty and Board of Trustees, and to offer African-Americans equal educational opportunities before the Emancipation Proclamation. Many of the now-common elements of today’s liberal arts education — self-designed majors, study abroad, interdisciplinary study, and portfolio evaluation — had an early start at Antioch. To keep his vision front and center, a framed daguerreotype of Horace Mann always hung on my office wall.

Finding the right facility, with the right vibe, was daunting. Attorney Ben Bycel, then dean of the Santa Barbara and Ventura Colleges of Law, let us sublet temporary space in their beautiful Riviera Campus — all for 17 cents a square foot. We loved taking coffee breaks at the adjacent El Encanto Hotel. Antioch moved downtown in 1977, into a small corporate office at 10 West Figueroa. Next was 23 West Mission Street. Finally, thanks to the generous Trust for Historic Preservation, Antioch moved to 914 Santa Barbara Street. On my first date with my architect husband, he climbed into the attic to see where the bearing walls were. I had many happy days sitting in my office in what is now Playa Azul.

I had no shame when it came to cherry-picking Antioch’s seasoned talent from Los Angeles and Monterey campuses. Program chairs Richard Whitney and Terry Keeney had the expertise to hit the ground running in recruiting students and hiring faculty. Within three months, my team had enrolled a small cohort of students enrolled in a bachelor’s in Liberal Studies and a master’s in Psychology. Pearl Fisher became an extraordinary Student Services administrator and the students’ trusted confidante. Antioch owes a debt of gratitude to the wonderful Core and adjunct faculty, all of whom made a whole-hearted commitment to the start-up effort.

An advisory council of businesspersons and UCSB friends helped me plan outreach strategies. I became a whirling dervish, speaking about Antioch’s uniqueness to every group I could find. Our $75 Independent ad read: “There are two campuses in Santa Barbara. We’re the smaller one!” UCSB had 16,000 students then, and we had 80. The ad created buzz for us. Chutzpah won!

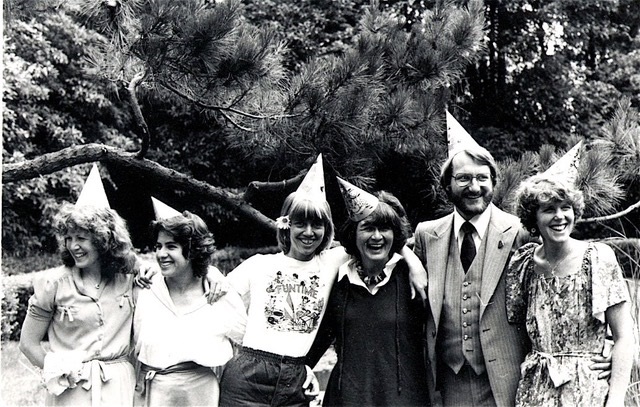

Despite my attempts to maintain a business-like environment, given our small size, the first crop of students insisted we were a “family.” We went through life-changing personal experiences together, from divorces and unexpected pregnancies to breast cancer and deaths.

Many of the BA students were people who had dropped out in the ’60s to participate in the social and anti-war movements, but by 1977, they wanted to complete their degrees. They forced debates about environmental degradation, gender, race, and peace — topics still being debated today. Alumni became professional advocates, therapists, nonprofit agency leaders, teachers, poets, artists, and entrepreneurs.

Although other universities were soon competing for the tsunami of older commuting students returning to college, I always believed that Mann’s historic legacy of integrating social justice awareness with a liberal education would distinguish Antioch from our competitors. To gain public attention, Antioch produced free conferences with thought leaders to include The Changing Nature of the Family and Designing the ‘80s.

Antioch Santa Barbara — and its 3,000 alumni — have contributed to the economic and social vibrancy of our community. With the increasing volume of reactionary voices in our country, I see an even greater need for university students to study and engage with society’s toughest problems in ways that will serve the public interest. Horace Mann got it right: Education needs to inspire each of us to achieve something bigger than ourselves.

A celebration of Antioch University Santa Barbara’s 40th anniversary will occur Sunday, May 6 with a production of Love, Loss and What I Wore at the Lobero Theatre.