April Is National Poetry Month

David Starkey Reviews a Book a Day

Former Santa Barbara poet laureate, and a book reviewer for the Independent, David Starkey does something special each year in honor of National Poetry Month (i.e., April) — he writes one review for every day of the month. The following are his book selections for this year.

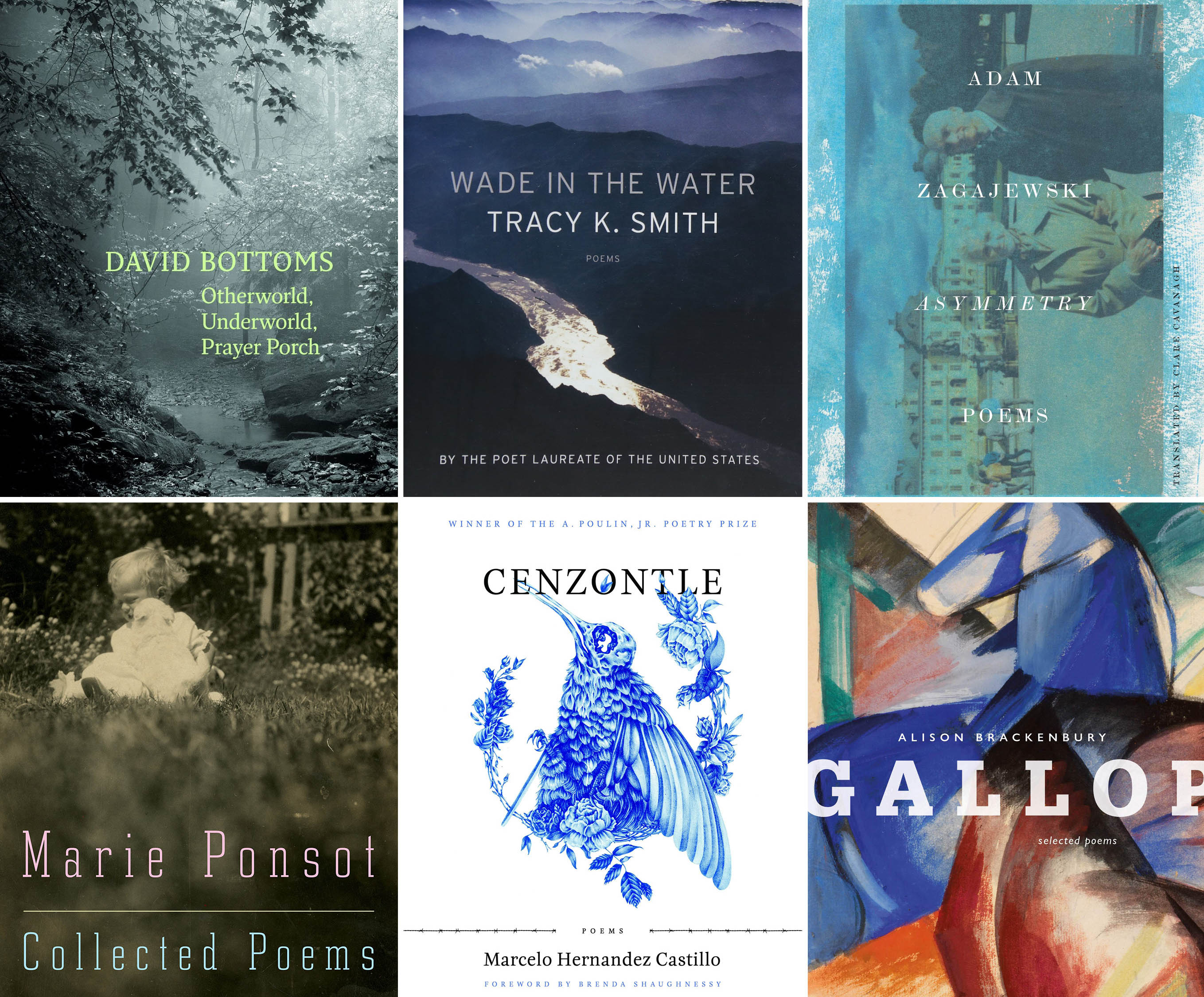

David Bottoms, Otherworld, Underworld, Prayer Porch: A sympathetic but unsentimental portrait of the white South: Baptist women, target practice with double-barreled 12-gauge shotguns, fields, barns, horses, and, above all, the connections among family that are as enduring as “the landscape / of your childhood.”

Tracy K. Smith, Wade in the Water: Being U.S. Poet Laureate during the Trump presidency can’t be easy, but Smith has managed it gracefully and without ever pulling punches. Her own verse is powerful, but the most striking poem in this collection may be a sequence consisting entirely of letters and statements from Civil War–era African-American soldiers and their dependents.

Adam Zagajewski, Asymmetry: In an elegy for a lawyer friend, Zagajewski points out, “Prosecutors multiply like flies, but defenders are few.” Clearly, his own sympathies also lie with the underdog, and these translations from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh present us with a poet whose work addresses the present, the historical, and the eternal.

Marie Ponsot, Collected Poems: “Alert & quickening,” Ponsot describes the winds in “Inside Out,” “like a school of minnows / darting in shallows over their shadows.” Those lines might also serve as her ars poetica. Throughout her Collected Poems, she moves from idea to image to emotion swiftly and with extreme grace.

Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, Cenzontle: “I’ve never made love to a man,” Hernandez Castillo writes, “I’ve never made love to a man but I imagine.” That sense of daring to envision a world that’s both/and — rather than either/or — is suffused throughout this collection of vivid, experimental, and extraordinarily musical poems.

Alison Brackenbury, Gallop: Selected Poems: One of the reasons rhyming poetry is so often absent from discussions of contemporary verse is because it is so difficult to write, and yet Brackenbury makes rhyming seem easy in work that is clever, controlled, eccentric, and thoroughly British in both subject matter and tone.

Chase Twichell, Things as It Is: “Falling leaf!” Twichell writes, “Stop for a second / so I can write on you.” Her ability to memorialize fleeting moments with striking imagery is evident throughout Things as It Is, a book that condenses a range of experiences — from sitting zazen to crying over Bob Dylan songs — into pithy and evocative poetry.

Michael Earl Craig, Words and Clouds Interchangeable: On first glance, Craig’s poems might seem a little too jaded and knowing — “I’ve been working on my Don Cheadle poem / for hours now and nothing’s happening.” But the more one returns to the work in Woods and Clouds Interchangeable, the clearer it becomes the true subject of his poetry is the pain of disappointment and loss.

J. Michael Martinez, Museum of the Americas: In addition to being a showcase for some smoldering linguistic skills and a powerful argument against racism, Museum of the Americas is also a memorial for the author’s mother. “The shoots bud upon the branch,” the poet writes in “The Wake of Maria de Jesus Martinez,” “& I say, I think we are loved. / & I know we are loved.”

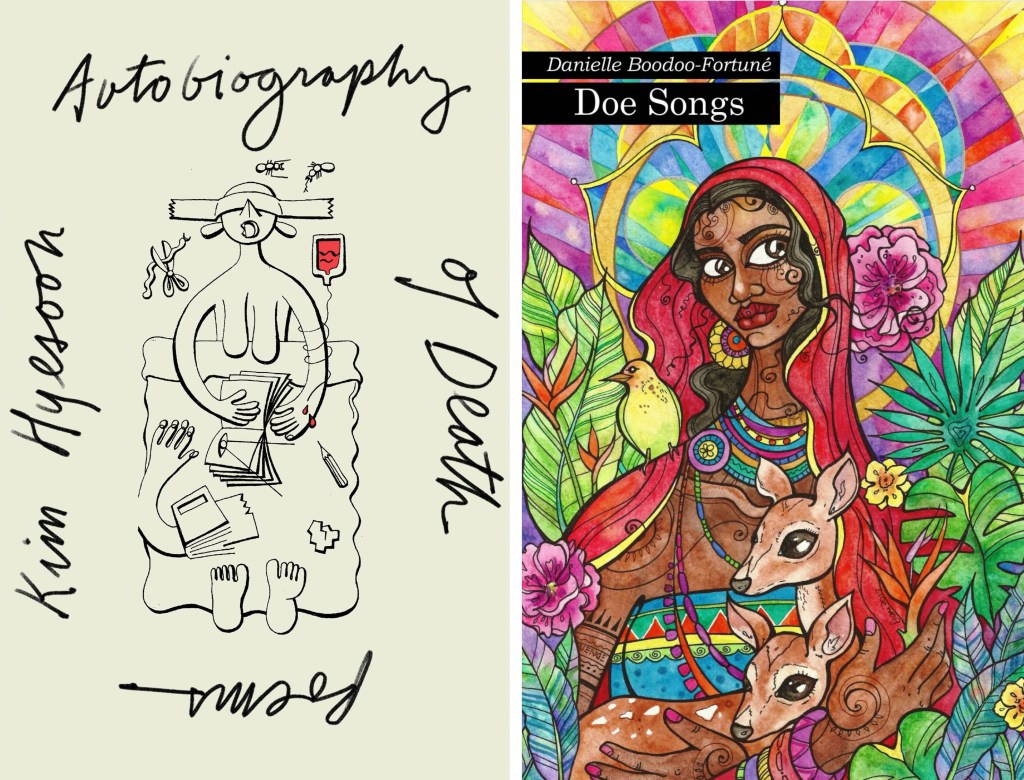

Kim Hyesoon, Autobiography of Death: Translator Don Mee Choi writes, “Each of the forty-nine poems in Autobiography of Death represents one of the forty-nine days during which the spirit roams about after death” before entering the cycle of reincarnation. The direct inspiration for Hyesoon’s poems might be the 250 high school students who drowned when a Korean ferry capsized in 2014, but clearly, she is speaking to anyone who realizes “the only thing you can offer yourself is your death.”

Shane McCrae, The Gilded Auction Block: Readers who have been waiting for a substantial and incendiary collection of poems responding to the election of Donald Trump need wait no longer. Appropriately, the book also examines the wellsprings of the Trump phenomena in searing poems like “Remembering My White Grandmother Who Loved Me and Hated Everybody Who Looked Like Me.”

Chris Tse, He’s so MASC: “The saddest song in the world has no title, no lyrics, melody, / no fixed abode,” writes New Zealand poet Chris Tse, “it floats between throats that harbor it.” The saddest song does, indeed, seem to be floating through many of the poems in this edgy, sometimes hallucinogenic collection.

Beverly Bie Brahic, The Hotel Eden: The book is titled after a Joseph Cornell box assemblage, and like the artist, Bie Brahic has an eye for the telling detail. In “Red Berries,” for instance, the speaker buys “two slabs / Of the wild salmon / Sweet butter / To seize it in / A wedge of ripe cheese.” Yet she is never satisfied with simple description. “Under every message,” she tells us, there is “another message.”

Ángel García, Teeth Never Sleep: Writing in both Spanish and English, García cuts across cultures and aesthetics. While poems like “Morning Breath,” “Self-Portraits of a Man as Beast,” and “Elegy for What Once Slept in a Cage” may make some readers uncomfortable, they are well-crafted and unflinchingly honest.

Sally Wen Mao, Oculus: The notes for Oculus are four pages long, suggesting something of the ambition of this book, which takes up issues of race, gender, media and history. “If our suffering is broadcasted,” Wen Mao writes, “let it be known. / Let it be collective. Let it be real.”

Doireann Ní Ghríofa, Lies: While these poems were originally written in Irish, the author’s facing page renderings into English never feel like mere translations. Instead, the poems are vibrant and musical, full of yearning for everything from the shadow of a lover’s hand to the “Secret melodies … concealed under winter wings.”

Danielle Boodoo-Fortuné, Doe Songs: Trinidadian poet Boodoo-Fortuné is also a visual artist, a gift she expresses not just through the fanciful shape of her concrete poems, but also through her deft use of imagery and metaphor. “What is this body,” she asks, “if not a map of punctures, / a glossary of bruises?”

Nicole Cooley, Of Marriage: The titles of these short, enigmatic poems — “Marriage as a Plate of Spinach” and “Marriage as a Skateboard Flung off a Bridge” — imply something of the book’s playfulness, but there’s also a real artistry in the connection between those titles and the poems themselves, as in the opening line of “Marriage as Motel 6 on Airline Highway”: “Tonight I rinse my black tights in the sink, twist the nylon tight.”

Sarah Corbett, A Perfect Mirror: Corbett’s creative engagement with earlier literary figures, including Marvell, Blake, and especially Dorothy Wordsworth and Sylvia Plath, is only part of the pleasure of this book, in which the poet treads carefully from line to line while retaining much of the wildness of spirit and thought she so clearly values.

Kevin Young, Brown: When Young quotes James Brown, “The one thing that can solve most / our problems is dancing,” you know he’s too wise to ever truly believe that, yet the power of music — and sports and poetry — to overcome at least some of the perils of life for African Americans is manifest throughout this wide-ranging book.

John Montague, A Spell to Bless the Silence: Selected Poems: Montague died in 2016, and this selection of his best poems is a worthy summing up of the work of one of Ireland’s most revered poets. Among his many gifts was an impeccable ear, as demonstrated in this description of driving along the then-border between the Republic and Northern Ireland: “the glistening main road / snowplough-scraped, salt-sprinkled, / we sail, chains clanking, / the surface bright, hard, treacherous.”

Jenny Xie, Eye Level: Xie’s poems are adventurous yet nuanced. Above all, she is a master of metaphor. “Sleep is a narrow corridor,” she writes in one poem, and in another, “The new country is ill fitting, lined / with cheap polyester, soiled at the sleeves.”

Terrance Hayes, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin: Every poem in this powerful and angry collection is titled “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin,” and all of them attempt, in one way or another, to address the catastrophe of race relations in this country. “Even the most kindhearted white woman,” Hayes writes, “Dragging herself through traffic with her nails / On the wheel & her head in a chamber of black / Modern American music may begin, almost / Carelessly, to breath n-words.”

Robin Robertson, The Long Take: A Noir Narrative: The Long Take was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in fiction, and yet this book-length work about a Canadian World War II veteran in America is clearly a work of poetry. Scottish poet Robertson skillfully creates the world of a man who has left a place that “was just the past” for one where “they’re only thinking about the future — / the past is being torn down every day.”

Emily Pettit, Blue Flame: “My name tag reads rabbit,” Pettit writes. “I am / the best refrigerator ever.” Many of her poems ping-pong from one subject to the next in a similar fashion. It’s an approach to language that will put off some readers, but excite many others who will enjoy the kinetic, rollercoaster experience of her poetry.

Steve McOrmond, Reckon: Canadian poet Steve McOrmond is an expert at sifting through the detritus of the modern world and separating the genuine from the phony, as in “Night of the Sitcoms,” where the “bread is sprayed with / lacquer, there’s no plumbing / under the sink, the stairs / dead-end in air.”

Sherwin Bitsui, Dissolve: In this collection of short, untitled poems, Navajo poet Bitsui slips in and out of the present and the past, reality and imagination. Almost every poem contains at least one striking, possibly indecipherable image like this one: “Semicolons coughed out by the final raven / sizzle the hand’s parched memory.”

Alice Miller, Nowhere Nearer: A New Zealander who has studied in America and now lives in Austria, Miller has a wide and varied perspective. Her poems aren’t quite surrealistic, but there is a strangeness to them that at times is eerie. “If you see them come,” the poet says of the those coming to take her to her grave, “warn them I plan / to sing my way out.”

Monica A. Hand, DiVida: Despite — or because of — the energy and life in DiVida, one can’t help feeling great sorrow that this posthumous collection was only Hand’s second book. Among the many treats in store for readers is an imagining of Othello at a house party: “how much money / do you even have Moor // just wait she will cuckold you / once she sees how black // you really are.”

Erika Meitner, Holy Moly Carry Me: Meitner writes with passion and insight about the America some of us would just as soon forget, one inhabited by Dollar General and Food Lion stores, where people spend their days jackhammering limestone and watching college football games, the names of their Wi-Fi networks popping up as you drive down the freeway: “default, linksys, virus, / GodisGreat, youfoundme, getlost, / JEMguest, batcave, funkchance.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.