COVID: The Artful Dodger

Santa Barbara County Cases Sail Up and Down the Charts

COVID continues to defy expectations, which has been the modus operandi of this highly adaptable virus since it sprang on the world in early 2020. Even with an 81 percent vaccination rate, 90,000 total cases, and unreported home tests, Santa Barbara County is nonetheless seeing an increasing spread, often through asymptomatic cases, as renewed infections in the jail demonstrate. At UC Santa Barbara, masks were on again indoors as of Thursday.

Santa Barbara County’s main jail cleared its last COVID case on March 2, after fighting it since December 8. This Wednesday, the testing system at the jail identified 12 positive inmates; one more was found on Friday. Of the 13 cases, 11 showed no symptoms, and all are being kept separated from other inmates. Visitation was suspended at the jail, and inmates’ court appearances are being rescheduled to avoid moving anyone who hasn’t cleared quarantine.

At UCSB, a significant increase in cases led to the indoor masking policy, only 10 days after the university canceled a required daily screening survey that barred symptomatic students and faculty from indoor spaces. Chancellor Henry Yang and other administrators urged them to take advantage of the no-cost PCR testing available on campus. With graduation ceremonies beginning June 10, media relations manager Kiki Reyes said that the outdoor ceremonies will not be affected but other indoor celebrations that take place on campus will, through to June 12.

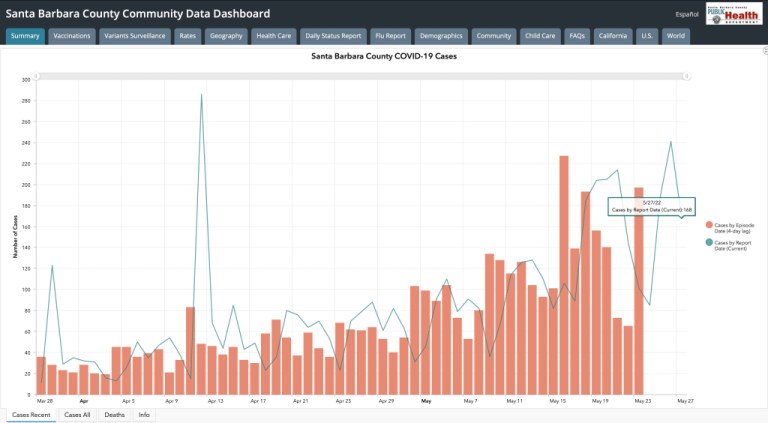

For the county as a whole, the daily number of new cases swings wildly. On Tuesday, between the Independent’s mid-day report and information released that evening, the new case counts sank from 219 to 85 on the county’s dashboard. With vaccination widespread and the virus less severe, the county updates the dashboard twice a week instead of daily, as it has for the past two hyperactive years. The vertigo-inducing changes continued with Thursday’s count at 241 and Friday’s at 168. In sober statistical terms, the seven-day average case rate — or cases per 100,000 residents — went from about 11 at the end of April to 30 on May 23, the last date posted.

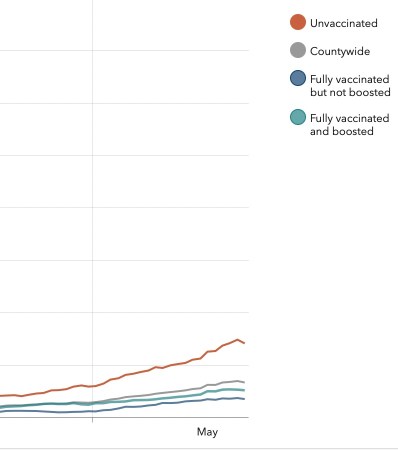

Unvaccinated persons continue to outnumber the vaccinated in positive tests, and hospitalizations have risen from single digits in April to 19 on Friday; three patients were in an ICU. Countywide, the first three weeks May have recorded no COVID deaths, a phenomenon also seen in May 2021; however, the pandemic has claimed 688 lives since March 2020.

Vaccinations began to be available less than a year after the epidemic broke out, but the virus has proved to be very clever in its evolution. The Alpha variant was found in December 2020, about the time vaccines came online; Delta arrived in the U.S. in June 2021, pushing ICU numbers above 20 locally when full vaccination was barely 60 percent; and Omicron arrived at Thanksgiving, casting off more and more contagious variants and re-infecting people who’d made it through a previous COVID illness.

Many question if vaccines work at all against this virus, but the question might properly be: Do they work against the current variant? The answer has been yes thus far. Though people catch the virus again, most are less sick and recover more quickly. To keep immunity levels high to resist infection and opportunities for mutations, booster shots are recommended. In an interview, Dr. David Fisk, an infectious disease physician at both Sansum Clinic and Cottage Health, explained the complicated, microscopic reasons why.

A virus duplicates billions and trillions times a day in an infected person, Dr. Fisk said. The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is considered very unstable and highly given to mutate during those trillions of replications. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 to a virus like polio, the genetic material in the polio virus is more stable and less changeable, Dr. Fisk said, and its vaccine works to protect against a relatively unchanging virus.

Location is another issue. Measles, like COVID, is highly contagious through sneezes and coughs, but similarities end at the attachment point the virus uses to enter the cell and cause infection. Studies indicate measles virus mutations at that cellular infection point render the virus unable to continue infecting human cells. The SARS-CoV-2 virus uses a spike protein to infect cells in the nose, throat, and lungs, however, and it has been a location for mutations; it’s also the protein that human antibodies attack. What’s different is that the SARS-CoV-2 mutations have made the virus even more infectious. The mutations also hold the potential for the virus to evade antibodies. While a vaccinated individual or someone who’s recovered from COVID can breathe in the latest variant again, the virus can sidestep some but not all the antibodies that react.

Viruses like SARS-CoV-2 — which is an RNA virus — change so quickly that creating vaccines for them are the most challenging to develop, Dr. Fisk said, using HIV and Hepatitis C as examples. There’s great global interest in developing vaccines for those diseases but no luck despite decades of research.

The variations emerging from the COVID virus to date have increased infectiousness, thankfully, rather than lethality. But, Dr. Fisk noted, “All it takes is for one to be different enough to have the advantage to be transmitted, and it’s off to the races.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.