Leonard Cohen Doc is Song-Rooted

HALLELUJAH: Leonard Cohen, a Song, a Journey, a Song Tells the Leonard Cohen Story, Through the Saga of a Song

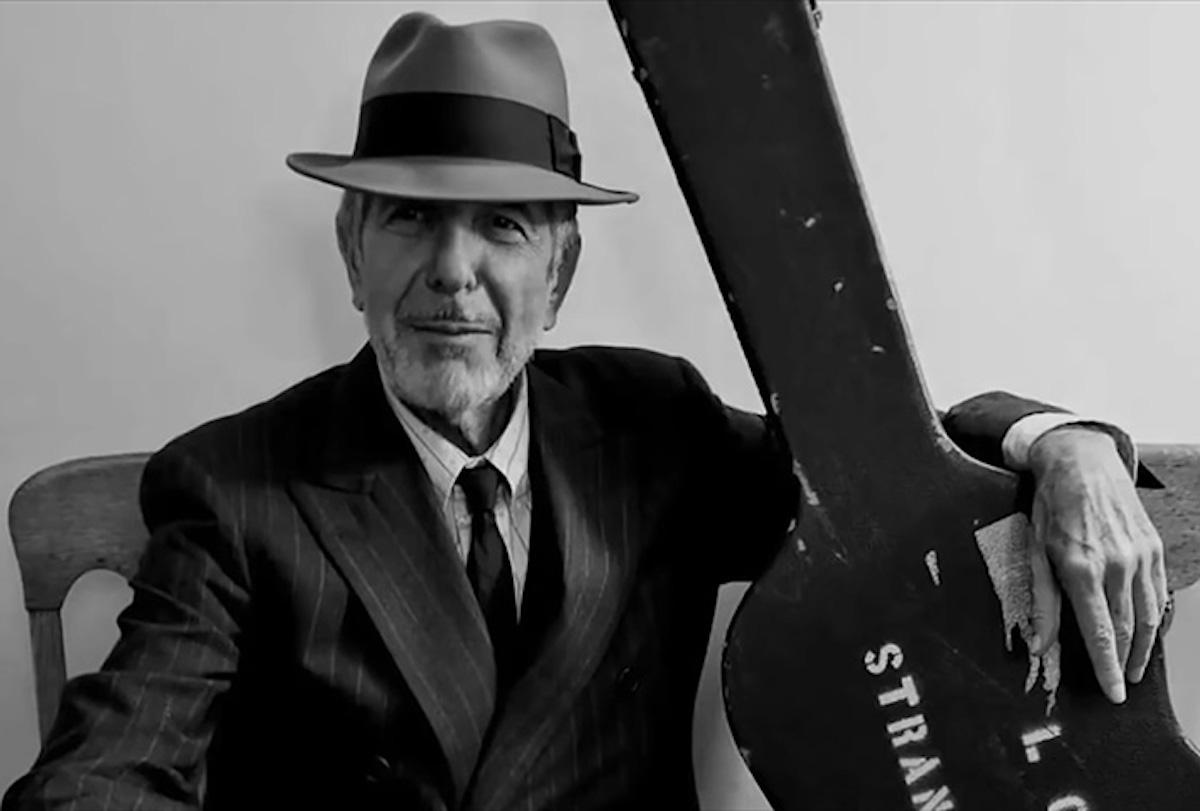

Leonard Cohen is dead. Long live Leonard lore. The great poet-singer-songwriter passed away in 2016, after spending many of the last years of his life touring to appreciative throngs (“it’s a good solution for old age,” he says drolly in the new doc Hallelujah, “you play until you drop”). Passions and reflections on the legend continue to hit bookshelves and big screens, from various angles. The binding theme of Nick Broomfield’s mostly career/life-spanning 2019 documentary Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love spins off and around Cohen’s relationship with his Norwegian girlfriend/muse.

The new film, HALLELUJAH: Leonard Cohen, a Song, a Journey, a Song, directed by Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine, is a deftly-made if sometimes meandering entry in the tricky music doc genre, which gamely banks on the power of perhaps his best-known song and its odd backstory and trajectory. Malcolm Gladwell has dissected the song’s power and saga in podcast form, but this film goes deeper, and goes vivid and vintage, fleshed out with archival footage — including dips into archives of veteran music journalist/Cohen confessor Larry “Ratso” Sloman — and Cohen’s quotable sound bites.

Strangely enough, the saga of Cohen’s semi-secular anthem — which we first hear him sing, on his knees in concert as an elder — had an obstacle-filled trek to mythic status. The original version was on a 1984 album prevented from American release by Columbia head Walter Yetnikoff (one of the film’s villains, along with embezzling manager Kelley Lynch, who left Cohen virtually penniless in 2005). Various outside parties helped cement the public resurrection of “Hallelujah,” including Bob Dylan, but especially emotive powerhouse Jeff Buckley and, via the film Shrek, John Cale and Rufus Wainwright.

By the time Cohen returned to the road, by necessity and then for love, the success of “Hallelujah” helped propel him toward pop culture sainthood and SRO houses. “The only way you can sell a concert is to put yourself at risk,” he says in the film. “If you don’t do that, people know. If you can inhabit that space and stand for the complexity of that situation, people feel good, you feel good and the band feels good.” His path to a good time entailed personal spiritual diving, melancholic baritone crooning and the anchoring force of a few timeless songs. This film takes an incisive aim at one of them.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.