Santa Barbara County to Be Fined $6 Million for Too Many ‘Canaries in Coal Mine’

State Mental Hospitals and County Jails Overwhelmed by Incompetent-to-Stand-Trial Population

The canary in the coal mine for the state’s fractured mental health and criminal justice systems is yet another obscure bureaucratic acronym: IST, which stands for “incompetent to stand trial.” That’s a legal determination made by a judge after consulting with two psychiatrists and refers to people charged with a crime who are mentally incapable of understanding the charges against them or assisting in their own defense.

For people like Lisa Y. — who spoke only on condition of anonymity — however, the real name of the condition is that of her fortysomething son who is now incarcerated in Santa Barbara County Jail; he suffers from acute schizophrenia, hears voices, and is highly delusional.

About six months ago, Lisa’s son was arrested after refusing Santa Barbara police commands to leave his studio apartment. He’d been playing music; a neighbor complained about the noise. The landlord called the cops. A small thing suddenly got very big. When Lisa’s son finally came out of his apartment, he was armed with a kitchen knife. A police dog charged. Seven inches of stitches later, Lisa’s son was in custody. On one level, she’s grateful. He could have been killed.

Three months later, Lisa’s son was legally declared IST. That means he should have been sent to Patton or Napa or any one of the State of California’s psychiatric hospitals to have his competency restored. But the demand for state hospital beds for IST patients is off the charts. In November 2021, there was a waiting list of 1,700. Four month later, it was 1,915, and growing. So for the past three months, Lisa’s son has been held in solitary confinement in county jail instead, with no transport date in sight. “He’s not a criminal,” Lisa says. “He hears voices.”

Stories like this are all too common throughout California and across the country. About 10 years ago, court administrators, mental health workers, and criminal defense workers began to recognize this was a “thing.” County judges, such as Brian Hill in Santa Barbara, issued rulings finding the Department of State Hospitals in contempt for failing to accommodate IST patients needing their competency restored.

Typically, IST prisoners would be in county jail for 120 days before being transferred to state hospitals, sometimes for as long as a year — where their conditions would get considerably worse. Once transferred, such prisoners — who happen to be disproportionately homeless — would spend on average 155 days in state care. But a research team found that even if their competency was restored, their underlying mental health issues remained. Recidivism rates for IST defendants hover at around 70 percent.

State hospital administrators have hardly sat on their thumbs. Since 2013, they’ve added 1,380 new beds. Still, the demand for restoration services has outstripped bed space.

Last year, the state legislature responded to local governments’ concerns by passing SB 184 — a carrot-and-stick budget measure. On one hand, the bill promises to deliver 5,000 new treatment beds over the next four years and has allocated nearly $1.2 billion to make this happen. On the other, it put county governments on notice that they will be penalized if their IST numbers go beyond the baseline set in 2021.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Santa Barbara County is already on track to be fined $6 million. In 2021, it dispatched 90 IST inmates to state hospitals. If these trends persist — 38 transfers in the first quarter — Santa Barbara will have sent 152 IST inmates to the state. Hence the $6 million fine.

That most definitely got the attention of high-ranking county executives who have created an interdepartmental working group with members from the court system, Behavioral Wellness, the Public Defender, the District Attorney, the county Probation Department, and the County Executives’ office. The $6 million will go into a state Mental Health Diversion fund, which the county can, in turn, apply for revenues to keep mentally ill people out of the criminal justice system in the first place. As such, they see the fine as an incentive almost as much as a sanction. It will help the county, they say, expand — and better integrate — Santa Barbara programs that are designed specifically to achieve that very goal.

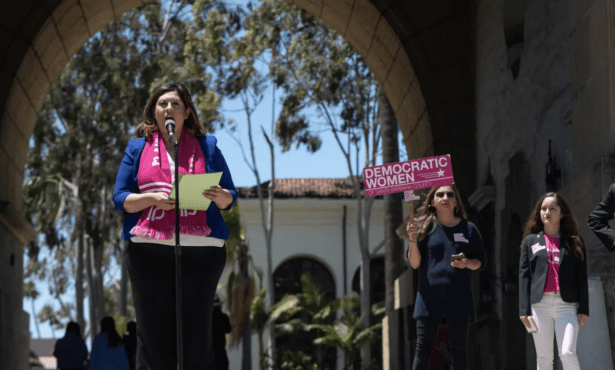

“I know a lot of families are suffering,” acknowledged Public Defender Tracy Macuga, an innovative champion of diversion and prevention efforts. “But when I started here six and a half years ago, none of these programs existed. I know we’re not moving fast enough, but we’re moving in the right direction, and we’re getting it right. I’m proud of what we’ve done.”

Under Macuga’s watch, the Public Defender now dispatches social workers to connect clients with mental health services, keeping them off court calendars. The county supervisors just committed to install 423 units of new prefabricated transitional housing throughout the county where mental health and detox services would be provided under intensely case-managed services supervision. Profound but bureaucratic changes in the state’s Medi-Cal system have just gone into effect that will now offer reliable reimbursements to agencies that hitherto had to scramble for grant funding. The county has one Multidisciplinary Task Force — made up of trained professionals who specialize in dealing with the most acute cases — and another is on the way. Probation has launched a program to hire people who used to be mentally ill as part of a peer navigation program.

As encouraging as all that undeniably is, key problems still exist. Data collection, sharing, and analysis are so fraught with legal and technical impediments that it is difficult to get accurate figures. Confounding matters are all the usual medical and legal confidentiality issues. Different departments use different platforms to store their data; many of these platforms are old and none allow the efficient transfer of data. On top of that, there’s a shortage of data analysts qualified to do the work. The county supervisors have budgeted millions in federal emergency COVID funding available to improve this, but it is still too early to bear fruit.

But for Lisa Y., none of this is happening soon enough. “Three months in solitary. No treatment. And no transfer date in sight.”

Correction: It was SB 184 that set the penalty for incompetent-to-stand-trial cases over the 2021 baseline.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.