Poodle Two-Fer: Santa Barbara Oil Company Fined $65 Million, and Enviros Oppose Refugio Pipeline Safety Valves

Greka Hit with Fine for Reckless Discharge; Refugio Pipeline Safety Valves Could Restart Oil Flow

HERE WE GO AGAIN: Once, we were all about kicking dogs while they were down. But here in Santa Barbara County, we like dogs — in fact, we take them out to dinner with us. So instead, we have settled on flagellating something called Greka Oil and Gas. Greka has operated so pathologically outside the pale of corporate conduct for so long that it was downright mythological. Even its owners finally felt compelled to change its name. It’s now HVI Cat Canyon, which in 2019 declared bankruptcy.

As an oil patch operator, Greka operated 11 facilities up in the Santa Maria and Cat Canyon areas with an outlaw abandon that seemed premeditated in the first degree. Based on its track record, Greka aggressively courted environmental catastrophe. It became the patron saint of perpetual oil spills, pipeline leaks, and corroded containment ponds. Not only was groundwater contaminated on Greka’s watch, but so too were nearby creeks that drain into the Pacific Ocean. This kept Greka constantly in the crosshairs of the Environmental Protection Agency, which is charged with enforcing the Clean Water Act.

I mention all this because late last week — on February 25 — a 61-year-old federal judge from Los Angeles named Fernando M. Olguin issued a 65-page ruling holding HVI Cat Canyon liable for $65 million in sanctions for violating the Clean Water Act as well as lesser state environmental infractions. That’s $1 million in fines for every page of the judge’s opinion.

At some time in history, $65 million would have seemed like a very big deal. But today, that — with the $5 bill you just found in the crack of your couch — might be able to buy you a small latte from the Dune coffee shop on State and Figueroa.

Given that HVI Cat Canyon declared bankruptcy four years ago and sold off most of its Santa Maria assets — which now sit dormant — it’s hard to believe much, if any, of that $65 million will ever get paid. And not to second-guess the judge — who, by the way, also ruled in another case that the grown man who was once the naked baby on the Nirvana album cover had no case to sue the band — but if you’re not going to get paid, why not go whole hog? The maximum penalty he could have imposed was $184 million.

Why equivocate over imaginary money?

Wading through the ruling was enough to induce dyslexia. But from what I gleaned, the case against HVI Cat Canyon involved just 12 oil spills that took place between 2005 and 2010. I say “just” because Olguin referenced 181 oil spills from 2006 to the present. Along the way 26,585 barrels of crude oil and produced water spilled into navigable waterways of the United States of America.

To be fair, only a small percent of that is actual crude oil, but the produced “water” is contaminated with scores of cancer-causing, birth-deforming chemicals. Its salt content is usually about 20 times greater than what ambient vegetation can tolerate and still live. Olguin clocked HVI as being in violation of one particular environmental regulation 86,842 days. The judge dismissed outright as “not credible” testimony by company officials that they genuinely tried to comply with the law. Instead the judge found the company displayed gross negligence and “reckless disregard.” Far more credible, Olguin found, was the expert witness who testified the company cut corners as part of its business plan, saving $6.3 million by not complying with protocol that would have drastically reduced the chances of such spills or minimized their impact if they did.

Contemporary and Premeditated

Still, $65 million is $65 million. Sure, it’s theoretical, but it’s not nothing. One might also wonder why it took so long. Greka, after all, was an openly oozing wound hiding in plain sight since forever. But perhaps Olguin’s ruling will serve some cautionary function, a bloody shirt waving in the wind. As outlandish an outlier Greka undeniably was, its conduct should serve as yet another wake-up call. (Given the more current mess still unfolding with Exxon and Plains Pipeline Company up the coast, I’d say we don’t need any more wake-up calls.)

HVI, it should be noted, walked away from its oil fields in Santa Maria, leaving 210 orphan oil wells behind. The California Department of Conservation, Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM) has been forced to assume control of the clean-up operations. But all of us — as taxpayers — will wind up paying the clean-up costs that Greka hasn’t and won’t.

Orphan wells are not just an unfortunate byproduct of some bygone day when boys could still be boys and oil companies could still get away with antiquated industry standards because no one allegedly knew better. You don’t get more contemporary and 21st century and premediated, knowing, and malicious than the mess Greka just up and left us with.

Industry apologists are forever arguing that oil development needs to take place right here in Santa Barbara because we have the world’s strictest environmental regulations. We can do it safely and responsibly, they insist. Not like the third-world despots who control much of the world’s oil supply.

It’s a nice line. For all I know, they may even believe it.

Next time you hear it, just get the speaker to buy you a latte with their proceeds of the $65 million Greka will never pay. And make it a large latte. With whole-fat milk.

Sign Up to get Nick Welsh’s award-winning column, The Angry Poodle delivered straight to your inbox on Saturday mornings.

Will Refugio Get a Valve Job?

In a perverse and intriguing way, the Planning Commission’s deliberations over adding 16 new safety valves to a stretch of the failed pipeline that gave rise to the 2015 spill tells much the same story but from a different and more convoluted perspective. For those tuning in late, a stretch of the Plains All American Pipeline burst a major leak back in May 2015 on the mountain side of the freeway. Somehow, 3,000 barrels of crude managed to escape and cross under both the freeway and then railroad tracks via a culvert and then collapse over the lip of a cliff that led the oil inexorably into the ocean where much marine mayhem then ensued.

Plains All-American would be criminally charged by Santa Barbara District Attorney Joyce Dudley and a Santa Barbara jury would find Plains guilty of one felony count and multiple misdemeanors for failing to take the necessary steps to keep its pipeline from corroding — which it did in multiple spots — not being adequately prepared for such a catastrophe, and then reporting the spill a day late and a few dollars short.

On a broader scale, this spill effectively shut down all offshore oil production off the Gaviota Coast, which in turn caused ExxonMobil to pull the plug on its massive production facility off the coast and eventually sell out its holdings to a murky new entity known as “Sable,” which looks suspiciously like the unfortunate love child arising from the incestuous union of ExxonMobil and Plains.

In other words, Plains All American single handedly killed Santa Barbara’s offshore oil industry.

It’s well recognized that much of this damage could have been averted had Plains All American outfitted its pipeline with something called “automatic shut off valves” that are triggered by any sudden shift in pipeline oil pressure. Plains, it would turn out, was the only pipeline within Santa Barbara County to refuse to deploy such safety precautions. In fact, its predecessor — Celeron Pipeline — had taken Santa Barbara to court and successfully resisted all entreaties to use such shut-off valves.

This Wednesday, the planning commissioners were asked to approve the installation of 16 safety valves onto the damaged pipeline. Exxon representatives argued they sought only to comply with a state bill that was passed in response to the Refugio oil spill — and written by then State Assemblymember — and now County Supervisor — Das Williams. The deadline for compliance, Exxon’s reps asserted, is a month away.

A Crazy Kind of Sense

The local enviro community — a broad coalition of both the usual suspects and newcomers to the fray — naturally opposed the installation of the new valves even though it’s what they have long stated should have been there all along. I know this sounds crazy, but in fact, it actually makes sense.

Adding significantly to the mix was attorney A. Barry Cappello, Santa Barbara’s resident legal barracuda, who reminded those present of how he’d been serving as Santa Barbara City Attorney when the late great Oil Spill of 1969, widely credited for sparking the emergence of the modern environmental movement. Few people enjoy the opportunities for theatrical expression offered by a courtroom — or a Planning Commission hearing — as much as Cappello, who represents a passel of property owners intent on renegotiating the pipeline easements they signed with the Plains All American for much more lucrative terms.

Capello wasted little opportunity to remind the planning commissioners that the applicant was “a felon.” He also reminded them that no one really knew who the hell was applying for the permits to install the safety valves. Was it Plains All American? Was it ExxonMobil? Was it Sable? And who the hell was Sable, he demanded? Did anyone really know anything about them?

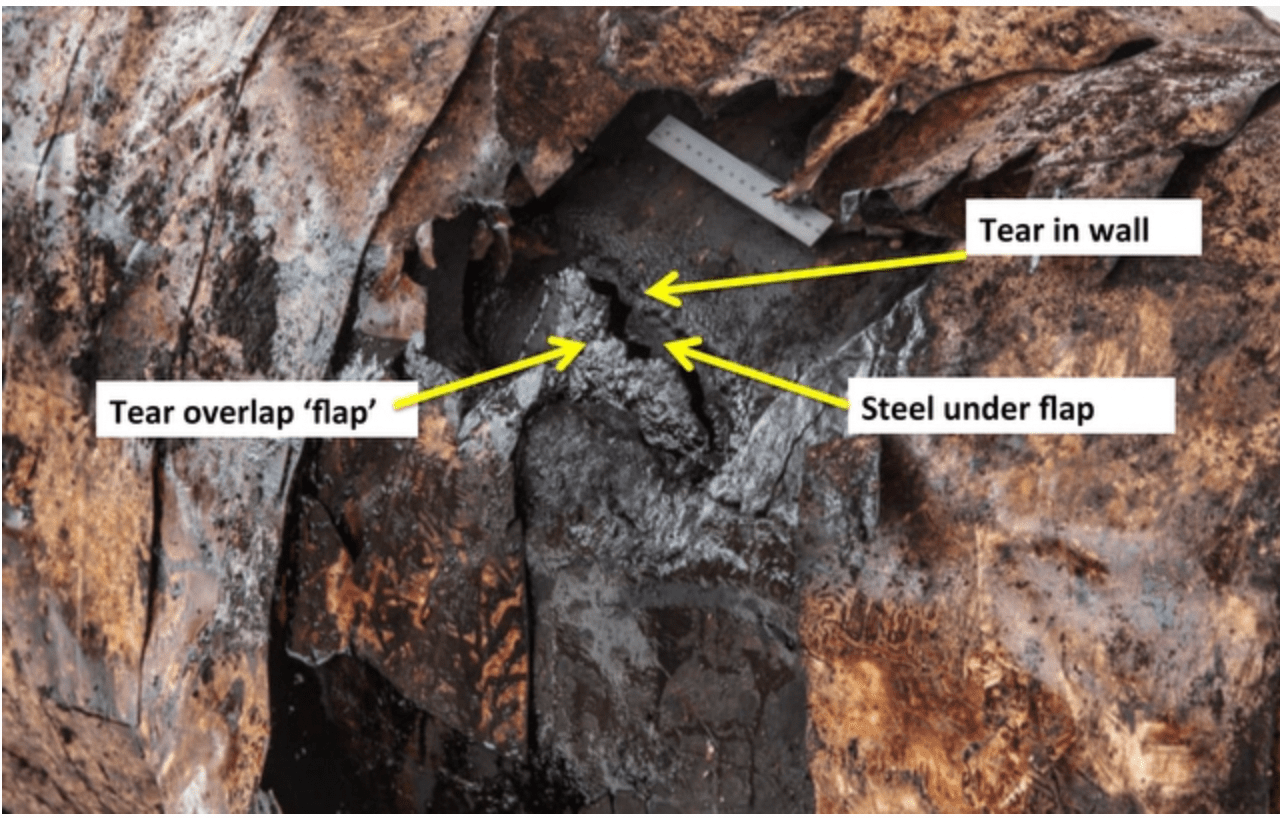

In case anyone missed it, Capello notified the whole world that he intended to fight whoever the applicant turned out to be. The existing pipeline, he declared, was a 180-mile stretch of “Swiss cheese” given how intensely and immensely corroded the pipeline had been allowed to become. Sable, Capello warned, had no intention of installing a new and improved pipeline — as federal pipeline safety regulators had insisted — but was hell bent on resurrecting the existing pipeline.

Every Dog Has Its Day

By contrast, the attorney dispatched by Exxon was soft-spoken, congenial, and non-confrontational to a fault. If he’d been any sweeter, the members of the commission would have contracted a collective case of diabetes.

Cappello and the enviro advocates pointed out — correctly — that if the county were to approve the new safety valves, it would surrender any further opportunity to comment on the impacts of re-activating the existing pipeline or imposing any new conditions upon it. They demanded a new environmental impact report, noting that the one for the existing pipeline was completed in 1985. Many of the mitigations called for in that document, they noted, had proven totally ineffective in preventing the corrosion and subsequent pipeline spill of 2015. If the pipeline were to be re-activated, Planning Commissioner John Parke opined, then ExxonMobil could re-activate its processing facility. This, he predicted, would trigger a 70 percent increase in the county’s total production of greenhouse gases. Shouldn’t that reality trigger further environmental review, he asked?

No one bothered to answer. The question, after all, was rhetorical. Except, of course, it wasn’t.

I was most struck by who didn’t talk. There was no one from the oil industry, for example, no hard-working guys wearing hard hats and glow-in-the-dark safety vests speaking movingly about their ties to the local community. No one from the school districts were there claiming they’d go broke without the property taxes generated by Big Oil. A couple of representatives from the chambers of commerce showed up, but they didn’t have any spit on their spit ball. Theirs were desultory performances. Andy Caldwell, the indefatigable champion of the oil industry and chief cook and bottle washer for COLAB (The Coalition of Labor, Agriculture and Business) was conspicuous by both his absence and his silence. ExxonMobil clearly kept their dogs in a kennel for the occasion.

They knew going in what the verdict would likely be. At least three of the commissioners were inclined to vote no. But they wanted county energy planners to come back at a later date with more information about requiring an environmental impact report. The energy planners aren’t entirely clear what kind of additional info the commissioners want, but they will hold a séance to figure it out. With or without a new EIR, it’s hard to imagine three votes in favor of the new safety valves. But without one, the valves are clearly dead in the water.

You must be logged in to post a comment.