Life Lessons from the Stories of Our Elders

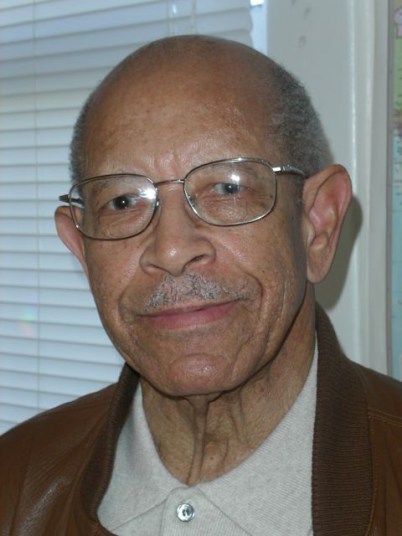

Dr. Arthur Norris Hicks: Going Beyond What Seems Possible

In the days when I was a middle-school teacher, my students and I decided to become story collectors, and we began an oral history project, meeting with folks in our community to gather memories and wisdom that might otherwise be lost to time. Our interviews sometimes involved a trek to a ramshackle house on a local ranch; other times, the interviewee would come to our school and we would gather together in the classroom or outside in the shade of a tree, hearing tales that now, years later, comprise a precious trove worth revisiting and sharing. One unforgettable visitor was Dr. Arthur Norris Hicks, an educator and human rights advocate who came to see us at Dunn Middle School in 2004, and whose story remains relevant and inspiring.

Born in 1922 in the heart of segregated Dixie, Art faced the ugly realities of racism right from childhood. “Even as kids, we understood,” he told us, “and in case we didn’t, they reminded us by throwing rocks through the window.”

He learned to live with anger. “But it was anger that had to be subdued,” he said, “and you felt a constant frustration. Once in a while you had to express it, but mostly you kept it inside. You learned how to survive, and how to maintain one’s mentality.”

In 1940, he noticed an advertisement in an Atlanta post office for an aircraft mechanic program run by the Federal War Training Service. He applied, was accepted, and was directed to come to a school in Memphis. He bought a one-way bus ticket with the earnings from his jobs as a janitor and porter. “But when I got there I was told, ‘You’re in the wrong place. This is for white boys!’ It was January, and it was cold, and I had used up all my money on bus fare. They said I would have to go to Tuskegee.”

He continued, “The problem is: how do I get there? I don’t have any money. It was suggested that I go to a travelers’ aid society, and there I was given the address of an elderly couple. Most hotels didn’t lend themselves to Black people in those days, especially in the South, so I stayed with this couple and worked as a busboy to earn the money, and then I went on to Tuskegee. So that’s the start of my education.”

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American aviators in the United States armed forces, and they served with distinction during World War II. “Blacks were considered incapable of learning complex material, incapable of flying a plane, incapable of carrying out military missions,” explained Art. “But in World War II, the nation was hurting for pilots and other technical types of skills, and it was a chance to convince the War Department and President Roosevelt to open up these opportunities for Blacks.

“My first solo flight was the most exciting thing I’ve ever done,” he told us. “I was about 20 years old in a little yellow plane called a Piper Cub. And to understand where I came from, what I had accomplished, and what hopes I had achieved … oh, it was indescribable.” He paused for a moment, remembering.

“But many Black men came back after serving their country only to be refused service at the lunch counters in their own hometowns.”

We asked Art if he ever got discouraged in the face of injustice. “I never get discouraged,” he said. “I get ticked off. It’s more useful.”

Art Hicks was small in stature — five and a half feet tall, and thin — but he had a big kind of courage and spoke out clearly when he saw unfairness. He served in the military for 28 years, working on airplane maintenance and missile guidance, confronting plenty of discrimination along the way, and choosing not to remain silent on the subject. He taught for 13 years at Cabrillo High School in Lompoc, earned a master’s degree at Cal Poly, and was honored with a doctoral degree from Tuskegee University for community service. He went on to see two of his grandchildren graduate from Harvard, received a belated Congressional Medal of Honor for his service as a Tuskegee Airman during World War II, and attended the inauguration of the nation’s first African American president, a once-unimaginable event. (“What a day that was!” he told me later. “You cannot imagine how it felt to be there!”)

Art died in 2017 at the age of 95. It was hard not to be inspired by this kind, spirited, and dignified man whose life was about working for change and transcending limits. As our interview drew to a close, one of the students asked Art if he had any advice to offer young people. His answer rings as true as ever: “I was exposed to despicable things early in life when I could do nothing about them, but I found much satisfaction after I discovered that I could take action and help create positive changes. We need to find it within ourselves to contribute to the whole, and we can most effectively do that by first making the best possible contribution to our own selves: through education, questioning, and personal growth. Then, stay on the path that leads to your goal. In fact, head for a goal that is so far out of reach you cannot even imagine what it is.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.