“How tall is too tall?” There’s a straight-forward answer to that: It’s anything beyond what the voting residents of a city have decided via their charters and ordinances. In an editorial recently, architect Brian Cearnal points out that our Santa Barbara City charter section, describing residential zoning limits to 45 feet in multi-family zones and 30 feet in residential ones, was set in 1972. Anything over the 60 feet allowed in commercial zones was considered a high building, he wrote.

That was overwhelmingly supported: 26,499 to 8,048. It would probably be similar now if there were an election asking the question.

Santa Barbara has long prided itself on being different from other Southern California cities. We are proud of our historic buildings and ambiance that attract so many. Celebrating that difference, providing the city lifeblood income are the visits of tourists from around the world. Its core is the human-scaled downtown and waterfront of varied heights, El Pueblo Viejo, with its revered — and protected — Spanish style. Tall buildings other than the isolated ones there now, would be antithetical “to the basic residential and historical character” of our city.

Yes, 2009’s Measure B (40 feet in El Paseo Viejo and 45 feet in other, commercial areas) lost, thanks in part to a set of very clever graphics and last-minute scare misrepresentations. There were10,343 voters who supported Measure B to the 12,009 in opposition. Since then, regrettably, there have been few to no efforts made by the prevailing side to work together with the proponents of Measure B.

However, the State of California has become much more dominant in land-use controls, with a state-wide proclamation of a “housing crisis” and an increasingly sharp-toothed Regional Housing Needs Allocation: Santa Barbara County is required to zone realistically for 24,856 units of which 8,001 are to be within the City of Santa Barbara.

Housing in Santa Barbara is a crisis, most would agree, but it is an affordability crisis. Cearnal argues that building tall would lower the cost of the housing units. It is a superficially clever argument. His assumption seems to be that the cost of land would be static, and if the expensive downtown land would hold more units, that would lower the cost of those units relative to the land. Unsaid is the probability that the upscaled land would become even more expensive and the units built would not be the “Affordable,” those built with subsidies, or even more than few (small “a”) affordable ones that we also need.

Santa Barbara architects and developers are not generally designing and building for the very low and low workforce our tourist economy needs. The Keyser-Marston study of 2017 pointed out clearly the nexus between upper income housing and the need for workers who are predominantly low to very low in income. More market-rate housing means more workers needed, exactly the demographic that is especially rental-challenged. Housing for the very low in income already depends largely on grants and other subsidies. An increase of upper-income residents would worsen the present crisis situation.

There have been few studies of the effects of rezoning on housing supply, including of rental units. If height limits were raised, would that produce more housing, lower rents, or no change at all to a city that has always been very much in demand, with its geography-limiting boundaries? The Urban Institute Journal article of March 29, 2023, reports on a study of 1,136 cities in eight metropolitan areas, including Los Angeles and Long Beach. They found that loosening restrictions, including height limits, resulted in a 0.8 percent increase in housing supply over 3-9 years. However, “This increase occurs predominantly for units at the higher end of the rent price distribution [and] found no statistically significant evidence that additional lower-cost units became available or became less expensive in the years following reforms.”

It is not helpful for Santa Barbara to gamble with loosening the protections built into our beautiful downtown, our El Paseo Viejo areas, only to gain more market-rate housing! Achieving such housing has not been a significant problem.

What Santa Barbara looks like, how livable it is, belongs to Santa Barbarans, not Bay Area legislators. It’s also not what local architects think would be best, although we’ve appreciated their charrettes.

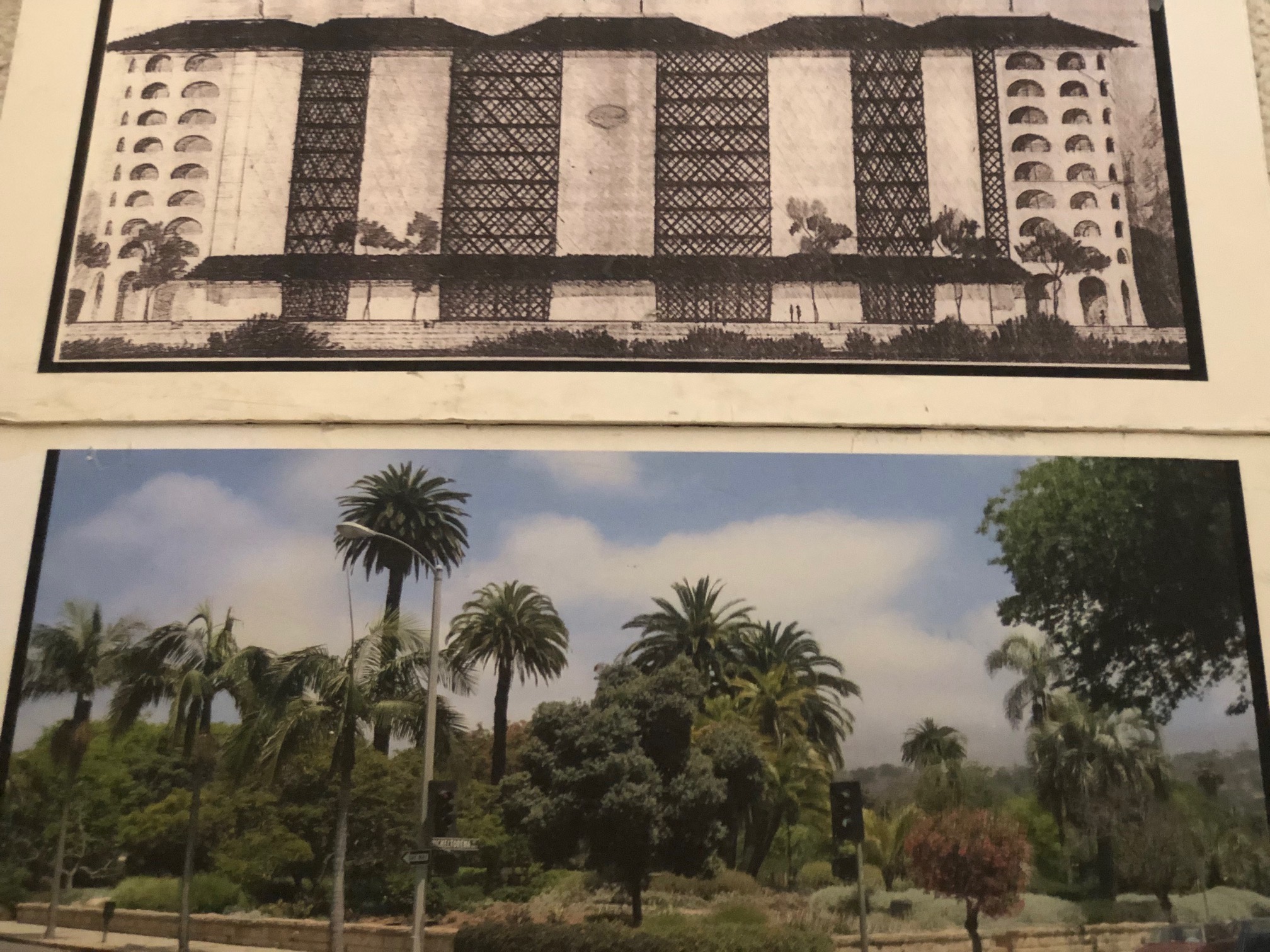

It’s what we, the people, want, as memorialized in our ordinances and City Charter that says how tall is too tall. And it is for those words, our Santa Barbara constitution, that we need to fight, just as neighbors and civic organizations, like Citizens Planning Association, did in the 1960s and ’70s, creating for all of us Alice Keck Park Memorial Garden, rejecting a developer high-rise for the few.