Buried within the “One Big Beautiful Bill” is what many see as a slap in the face to front-line healthcare workers. According to a November 6 press release from the Department of Education, nursing — along with several other health and education fields — has been excluded from the newly revised list of “professional degrees.”

The decision imposes strict caps on student loans for graduate-level programs. Students pursuing degrees not deemed “professional” by the federal government will be limited to $20,500 per year in federal loans, with a $100,000 lifetime cap. In contrast, students in approved “professional” programs — such as medicine, dentistry, and law — can borrow up to $50,000 annually, with a $200,000 lifetime cap.

Nursing didn’t make the cut.

“They’re saying we’re not professional enough. That’s the message,” said Sandy Reding, a Bakersfield-based operating room nurse and representative of National Nurses United. “This is not only disrespectful but a financial barrier for nurses who want to advance their education.”

In Santa Barbara, the exclusion feels not only offensive but deeply disheartening to nurses working their way up the ranks.

At Santa Barbara City College, the nursing program offers only associate degrees. “These changes do not impact our nursing programs,” confirmed Rosette Strandberg, SBCC’s Director of the Vocational Nursing Program. But many SBCC students plan to continue their education, and that’s where the impact hits.

“I have friends who want to go to NP [nurse practitioner] or CRNA [certified registered nurse anesthetist] school,” said Savannah Boehmer, a fourth-semester nursing student. “They’re all pretty upset because they’ll now have to take out private loans, which are harder to get and come with higher interest. It sucks.”

Brittany Jordan, also an SBCC nursing student and practicing respiratory therapist, is planning to pursue a CRNA degree — a doctoral-level specialty. “I probably won’t qualify for personal loans,” she said. “And those programs cost anywhere from $98,000 and up. This change just cuts people like me out.”

Jordan acknowledged the administration’s stated reasoning: that limiting federal borrowing could pressure graduate schools to lower tuition. “But that’s not a guarantee,” she said. “Meanwhile, people like me who can’t qualify for private loans just get left behind while we hope schools get cheaper someday. I’ve never seen that happen.”

Advocates warn the new rule could discourage nurses from pursuing advanced degrees, deepening the staffing crisis in rural and underserved areas. According to National Nurses United, the issue isn’t a shortage of licensed nurses — but a shortage of nurses willing to work under current conditions. Unsafe staffing ratios, sicker patients, and burnout have pushed many away from the bedside.

The stakes are especially high in Santa Barbara County, where access to physicians is already stretched thin. The current patient-to-primary-care-physician ratio here is approximately 1,305 to 1. While the county isn’t officially rural, many inland and outlying communities experience rural-like barriers to care. In these gaps, advanced practice nurses — like nurse practitioners and CRNAs — often serve as primary providers. If fewer nurses can afford to pursue these degrees, the cracks could widen.

“We have over a million licensed nurses in this country,” Reding said. “But they’re not working in hospitals because of the conditions. The corporations have manufactured this staffing shortage.” She added that for every additional patient assigned to a nurse’s workload, patient mortality increases by 7 percent.

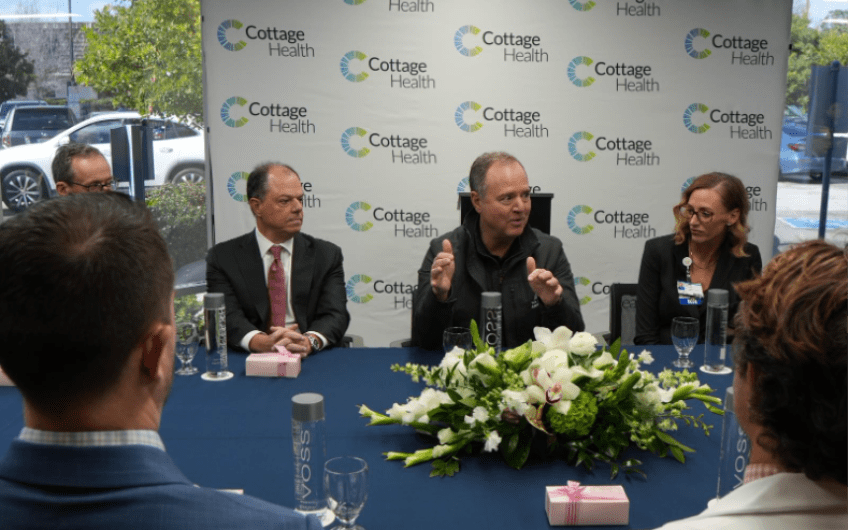

Meanwhile, Cottage Health — the region’s largest employer of nurses — declined to comment.

“This affects who gets to be a nurse practitioner, who can afford to teach nursing, who fills in the gaps where there are no doctors,” Boehmer said. “It’s not just policy — it’s public health.”

The Department of Education is accepting public comment on the proposal, which is set to take effect on July 1, 2026.

“If you want to solve the staffing crisis,” Reding said, “fund our education and fix the working conditions. Ask the nurses. We already know the answers.”

Premier Events

Fri, Mar 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07

9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Sun, Mar 01

7:00 PM

Goleta

Natalie MacMaster, Donnell Leahy, Celtic All Stars

Fri, Mar 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06

8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Mon, Mar 09

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28

All day

Santa Barbara

Coffee Culture Fest

Fri, Mar 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07 9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Sun, Mar 01 7:00 PM

Goleta

Natalie MacMaster, Donnell Leahy, Celtic All Stars

Fri, Mar 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06 8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Mon, Mar 09 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Science Pub: Cyborg Jellies Exploring Our Oceans

Sat, Mar 28 All day

Santa Barbara