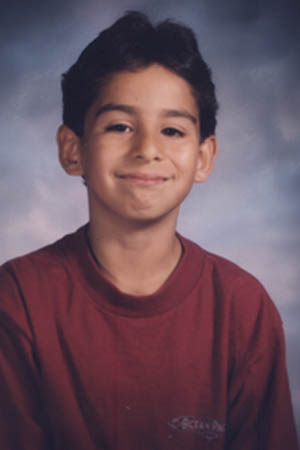

Army Specialist Jaime Rodriguez Jr., 1987-2007

A Soldier Comes Home

When the Kalitta Charters airplane carrying the body of U.S. Army Specialist Jaime Rodriguez Jr. landed at Santa Barbara Airport just before 2 p.m. on Thursday, August 2, the jet also brought home what the South Coast had avoided for more than four years-a young soldier killed in Iraq. The 19-year-old Rodriguez died July 26 when an Improvised Explosive Device detonated near his vehicle in Saqlawiyah, a city just northwest of Fallujah in Anbar province. Sgt. William R. Howdeshell, 37, of Norfolk, Virginia, and Spc. Charles E. Bilbrey Jr., 21, of Oswego, New York, from his unit also died from the blast.

About 50 members of Rodriguez’s family were at the airport. The charter plane touched down, taxied to Mercury Air Center, and came to a stop not far from the waiting group of mourners. As the brown wooden casket draped with an American flag was lowered, the plane’s two pilots, a soldier wearing the distinctive Army-green uniform, and six members of the Honor Guard all saluted. The only noise that could be heard was the buzzing of a nearby plane as the Honor Guard members, dressed in dark blue uniforms and white gloves, slowly carried the casket away from the plane.

The scene was solemn and tragic. Members of the Mercury Air Center staff stood on the tarmac for the ceremony while three men who had just arrived in a private plane stood respectfully outside their aircraft. Rodriguez’s mother, Dulce Soto, and her youngest son, Alex, walked hand-in-hand to the casket, followed by tearful family members, many of whom were wearing photos of Rodriguez tied on strings around their necks. After the family had spent a few moments at the casket, the Honor Guard carried it to the hearse that was waiting to take it to Welch-Ryce-Haider Funeral Chapel, where there would be a visitation later in the day, followed by a vigil that night at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Carpinteria. After closing the door to the hearse, his cousin, Jahir Garcia, a U.S. Marine in full-dress uniform, saluted Rodriguez, then put his fist to his mouth and walked away crying.

to Spc. Jaime Rodriguez Jr. before his burial at Santa Barbara Cemetery.

For many people around the country, Rodriguez will become another name added to the growing list of more than 3,670 U.S. servicemen and women who have given their lives in Iraq. In California, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger ordered-as he does whenever a Californian is killed in combat-state capitol flags to be flown at half-staff in honor of Rodriguez. Schwarzenegger also issued a statement saying the 19-year-old “joins a proud legacy of heroes who fought for their country and gave their lives to protect their fellow Americans,” a statement similar to the ones he had previously issued for the four other soldiers and marines from Santa Barbara County who have already died in Iraq. But to the 50 or so family members waiting on the tarmac Thursday afternoon, to the hundreds of friends gathered for the funeral at St. Joseph Church, and to a whole community in Carpinteria, it won’t be as easy.

“He always had a great heart.”

Jaime Rodriguez Jr. was born on October 14, 1987, in the City of Santa Barbara, the second of three children to Jaime Rodriguez and Dulce Soto. He was nicknamed “Pollito”-Spanish for “little chicken”-when he was three months old because his mother dressed him in yellow pajamas. Jaime, with his older sister Elizabeth and younger brother, went to school in Santa Barbara until his parents divorced in 2000 and his mother moved to Carpinteria. Rodriguez attended Carpinteria High School starting in 2001, and even after Soto moved to Oxnard, he remained in school there. His mother would drop off Jaime and Alex near the school on her way to work in Goleta. In high school, he ran track and cross-country usually as the sixth or seventh man on the cross-country team, and in the 400- and 800-meter races. He wasn’t the star of either team, though in his senior year he did finish sixth in the 400-meter race at the S.B. County Track Championships. But it’s not his athletic prowess his coaches remember; rather, it was his leadership and determination.

in Fort Knox, Kentucky

John Larralde, now an assistant cross-county coach at Westmont College, worked at Carpinteria High when Rodriguez was a student. He called Rodriguez a stabilizer on the team; “Guys listened to him,” he said. And he was always doing what he was supposed to be doing, according to Ben Hollack, an assistant track coach who also taught Rodriguez science his sophomore year of school. The kind of kid who didn’t belong to any one clique, Rodriguez could finesse all his peers with grace, according to Art Monarres, a Carpinteria High physical education teacher who taught Rodriguez for three years and had him as a teacher’s aid for a fourth. “I can still remember him as a freshman in PE class; this small, little kid. But he always had a great heart,” Monarres said.

Rodriguez did okay in school, but was never a big fan of it. “He didn’t like to do homework,” Soto recalled. “That was his biggest problem. He’d carry his backpack with only a notebook and pen in it.” His teachers and friends remember people gravitating toward his good nature and humor. “Jaime was the best friend anyone could want or have,” Michael Sandoval, Rodriguez’s friend from Carpinteria High, wrote in an email. “He was just the coolest to be around. He always made me laugh.”

Carpinteria High teacher Monarres remembers Rodriguez asking him to keep tabs on his younger brother, Alex, while he was overseas. So, whenever they’d run into each other at school, Monarres would ask Alex how he was doing. Monarres said he talked with Alex, who will be a sophomore in high school this fall, at the vigil last Monday: “‘Hey, you know how I’m always asking you how things are going?’ I said, ‘Well, I did that because Jaime asked me to. He was looking out for you.'” Rodriguez liked picking on Alex, who said his older brother would pin him on the ground and poke him in the ribs. “He was a pretty good kid,” Soto said. “He was quiet and playful. He was always making jokes.” He used to call her fat, his way of telling her that he loved her. “We all knew what he meant when he called me fat,” she said.

The Road to Iraq

Known as Gandhi to his friends on the cross-country and track teams, Rodriguez got his nickname because of his wire-rimmed glasses and skinny frame. He was even called scrawny and lean by some of his teachers, and was described as an unassuming kid who few predicted would become a military man. Monarres said, “I never pictured him as a soldier.”

Rodriguez, however, enlisted in the Army soon after graduating high school in 2005, joining two fellow graduates and friends, Marine Corps Reservist Rodrigo Gonzalez and Army soldier Luis Arreola, according to Monarres. Rodriguez listed Oxnard as his home address where his mother was then living. According to others, he always had a high admiration for the military, and had considered joining the Air Force, but knew he wouldn’t be accepted because of his poor vision. His mother remembered how he wasn’t ready to go to college. He told her, “Mom, you know I don’t like school.” So, Soto said, “I told him to find a job.” In the summer months after graduating, he hung out at home, went to the pool, and played video games. During his job search, Soto asked him if he’d thought about joining the Armed Forces. Rodriguez did some research, and after speaking with a recruiter, he decided to join the Army. Monarres said that soon after, Rodriguez told him, “‘I just want to help, I want to go do something.’ He knew he was going to Iraq.”

After his basic training in Fort Knox, Kentucky, Rodriguez returned to Carpinteria for a couple weeks in spring 2006. “He had a different perspective,” Carpinteria High School’s track coach Van Latham said. “He seemed to have a more focused vision of where he was going. He looked great. He was very proud of getting through camp.” His official Army photo shows Rodriguez sitting in front of an American flag, dressed in fatigues, his hat pulled down so low his eyes can barely be seen. It’s a serious young face, portraying Rodriguez as a soldier, as a man.

“He was different,” Soto agreed. “He wasn’t the little kid I let go of five months before. He was more mature.” After his break, Rodriguez returned to Fort Stewart, Georgia, where, in January, he became part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. As a cavalry scout in the 5th Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division, Rodriguez took part in foot and vehicle patrols, combat and search operations, and worked with the Iraqi army. Monarres would get email updates from Rodriguez semi-regularly, some of which Monarres would read to his classes. In the letters, Rodriguez would describe what he was doing. “It looked like he was going, ‘Oh boy, this is for real,'” Monarres said. When Rodriguez was killed, he had less than a month before a scheduled two-week leave in August.

“Death always comes without knocking.”

Soto heard the devastating news that her middle child had died on July 30 when an Army lieutenant, accompanied by a Santa Barbara police officer, knocked on her door. A vigil was held in his honor that night on the beach in Carpinteria. More than 250 people attended his funeral at St. Joseph Church on Friday, August 3, including Carpinteria Mayor Michael Ledbetter and an assistant from Rep. Lois Capps’s office.

The funeral was led by Fr. Adalberto Blanco, who spoke in both English and Spanish to the crowded sanctuary. “This is one of those times when there are no words to describe what this event really means; it’s too overwhelming,” Blanco told the mourners, about half of whom were wearing white. “Death always comes without knocking.” Fr. Tom Kelly from Vandenberg Air Force Base told the crowd to “remember the constant struggle that goes on for freedom. Jaime died an honorable death for his brothers and for the cause of freedom.”

Many of the people gathered at St. Joseph Church made the nine-mile drive to Santa Barbara Cemetery-Jaime Rodriguez’s final resting place-where they gathered on top of a hill near an American flag flown at half-mast. After the casket-with a U.S. flag draped over it and Rodriguez’s Army dog tags hanging from one of the handles-arrived, Frs. Blanco and Kelly and members of the family, one by one, sprinkled the site with baptismal water.

After a long period of silence, a three-volley salute from the six-man Honor Guard sent a shock wave over the mourners. The Honor Guard, with the muzzles of their rifles pointed up over the casket of Rodriguez, fired in unison, followed by a wrenchingly slow bugle rendition of “Taps.” The Honor Guard then ceremoniously folded the flag from the casket, and U.S. Army Brig. General James Chambers presented each parent with an American flag, and five posthumous medals-the Army Good Conduct Medal, a Purple Heart medal, a Bronze Star Medal, and two for serving in the Iraq War-while an officer read off the merits for the awards. The Bronze Star Medal, given for service and bravery, is the fourth highest combat award of the U.S. Armed Forces.

The funeral director then announced the end of the ceremony, thanking everyone on behalf of the family, but no one could bear to leave the site. Instead, they stood in silence around the gravesite. One by one, family members, dressed in white and many wearing black-and-gold remembrance ribbons, got up to pay their final respects. Soto, with her youngest son, Alex, again by her side, approached the coffin one last time, laid her head on the wooden cover, and embraced her dead son as best she could, extending her arms around the coffin. It was a scene sad enough to break anyone’s heart, and a reminder of the sacrifices being made. “It’s a shame to see,” Larralde said. “We seem to be losing our best young men. It really seems to come back to you when it hits you personally.”

“I’m struck by this loss, that this just shouldn’t happen,” said an emotional Hollack. “I would’ve looked forward to teaching and coaching his kids. This is a tremendous loss. I hope the government is acting in a way that is responsible for the sacrifices that are being made. They’re taking away some of our best.”

“I’d had other students go and come back,” Monarres said. “When I said goodbye to Jaime, in my heart, I thought I’d see him again. But he didn’t come back.”

“I’ll always be waiting for him,” Soto said, “waiting for his phone call.”

S.B. County Iraq War Deaths

Lompoc

Air Force Captain Derek Argel: d. May 30, 2005

Santa Maria

Marine Corporal Joseph J. Heredia: d. November 20, 2004

Marine Corporal Garrywesley T. Rimes: d. April 1, 2005

Army Sergeant Shawn E. Dressler: d. June 2, 2007

Santa Barbara

Army Specialist Jaime Rodriguez Jr.: d. July 26, 2007