Playing the Race Card

A Former Teacher Ponders What Really Makes Kids Achieve in School

These are not just economic achievement gaps,” said California’s schools czar Jack O’Connell last August. “These are racial achievement gaps.” With this controversial statement, the California Superintendent of Schools presented public school students’ standardized test results. As usual, there were distinct differences between the scores earned by various ethnic groups, with Asians scoring very high, whites trailing them, and Hispanics and blacks bringing up the rear.

O’Connell’s words got my attention. Besides the shock value, their beauty as a political pronouncement is that they can mean anything the listener wants to hear. From one end of the spectrum, it means our schools are bastions of institutional racism. From the other end, it means the schools are doing as well as can be expected, considering the racial deck they’ve been dealt.

Generations of schooling

O’Connell’s racial pill isn’t being swallowed by the Santa Barbara School District, where one civil servant remarked dryly, “He is running for office.” (O’Connell is considering a campaign for governor.) According to the district’s superintendent Brian Sarvis and statistician Davis Hayden, the most pertinent factor in students’ achievement is their parents’ education, especially the mother’s.

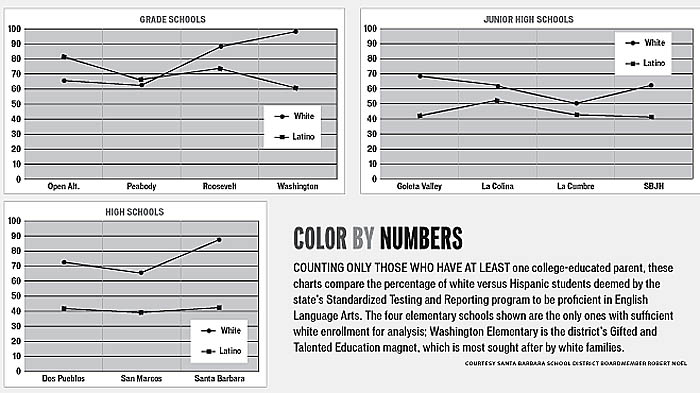

Among students who have at least one college-educated parent, the gap is small between Hispanic and white elementary school students. But that gap widens during junior high and becomes a yawning chasm by high school, particularly in the English language arts. Math scores don’t diverge as much. (As for Asians, their numbers in Santa Barbara schools are too small to be statistically significant for this particular chart.)

So if parents’ education is the most important factor, why is the achievement gap still there? Theories abound, including some pretty stupid ideas about racial IQ. However, Hayden suggested white students may have more than one college-educated parent, and those parents may also have postgraduate degrees. He also surmised that white parents are less likely to be first-generation college-educated, so their children are more likely to be surrounded by educated relatives and family friends. Income differences are another important factor, which are not shown on this chart.

It’s not just poverty, though: Nearly half of impoverished Asians tested at or above grade level in English language arts, compared to just a quarter of impoverished Hispanics. In O’Connell’s February State of the Schools address, he hypothesized a class of 32 students “representing the diversity of our state and the potential of our future.” Four were Asian-American, and all of them will graduate from high school. Two of the nine white students would not, nor would one of the three African Americans. If graduation rates aren’t improved, said O’Connell, six of the 16 Hispanics will not graduate.

To the ear of this former teacher, what O’Connell is clearly saying is that educators need to use methods that take advantage of a culture’s intellectual strengths, such as the rich oral tradition among Latino and African-American families. As someone who’s seen such students’ brilliance firsthand while watching their test scores flounder, I couldn’t agree more.

Gauging the Gap

Take my Latina friend Estella. In her twenties, when I was hanging out with her, Estella could make people laugh long and hard simply by giving an account of an otherwise mundane event like taking out the trash. But while her narrative skills were unrivaled, she didn’t even come close to graduating from high school. Her parents were working-class Latinos, and her whole generation-brothers, sisters, cousins, in-laws-was obviously intelligent, like her. But you’d never accuse them of being academically accomplished. They’re a collection of sinners and saints like the rest of us, but in a very direct way: One sister takes care of severely disabled children, a brother recently died of a drug overdose, and another brother is in prison. Does this not uncommon scenario mean Hispanic underacheivement is chiseled in stone?

Certainly not. One of Estella’s nieces-after leaving school at age 16 and later getting pregnant while in the military-is now doing great at UCSB, earning a 3.9 grade point average while working as a phone operator and raising her two children who are enrolled at the Santa Barbara Academy. Formal education is genuinely interesting and important to her. Which is to say that vast, unexploited intellectual wealth thrives within the Latino culture.

Searching for Solutions

A former teacher himself, Jack O’Connell has been thinking about education for a long time-and putting those thoughts into action. He’s responsible for both the high school exit exam and the mandated 20-1 class-size ratio in the lower elementary grades, two radical measures he pushed through as Santa Barbara’s representative in the State Senate. O’Connell was also a prime mover in reducing the requirement from two-thirds to a 55 percent majority for passing bonds to build and repair schools.

It’s difficult to tell why O’Connell has chosen to hang his hat on this ethnic analysis, since it does not suggest any obvious solutions to the problem of low Hispanic achievement. And that problem-considering Hispanics are the state’s fastest growing ethnic group and that underacheivement translates to higher crime rates and other social costs-must be one of the state’s biggest.

When I called to set up an interview with O’Connell, I asked his press secretary, Hilary McLean, what actually works to boost Hispanic achievement levels. “If it was known how to close the gap,” she said, “we’d be doing it now.”

O’Connell called a few minutes later to correct his staffer, explaining, “It’s not exactly accurate to say we don’t know what works.” He then went into some of his boilerplate commentary, which sounds like the same old song and dance: higher expectations for students, more engaged parents, proper utilization of technology, and a motivated teacher in front of every class.

He’s right, of course, but his focus is on creating higher-quality schools in poor neighborhoods. In relatively affluent Santa Barbara, however, Hispanic students still fall behind their peers even in good schools. O’Connell has no skeleton key for unlocking such a complicated problem, unless it is to reduce class sizes even more, all the way down to just 15 kids per teacher. And that, at a time when teacher layoffs are more common than hiring binges, appears prohibitively expensive.

In the meantime, O’Connell is holding a summit in Sacramento next month to start hammering out policies to close the ethnic gap. By bringing together thousands of educators to meet with the experts in his office who have been studying stats and analyzing data about the racial divide, O’Connell hopes to make some much-needed headway.

But why have our schools been unable to solve the problem of low achievement, especially among Hispanics and African Americans? I have a few ideas about this, having spent three years at the turn of this century teaching for the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) in classrooms full of Latino immigrants, followed by a year and change in the Goleta Union School District. I could tell you stories of deficiencies in the system that would make your hair stand on end, but a short list would have to include ill-paced curriculum, grading systems that are random or demoralizing or both, and expensive computers gathering dust without the expertise or the software to make them useful. Another problem is that teachers like me-long on passion but short on skills-are thrown like raw meat into classrooms with 20 or so Spanish-speaking seven-year-olds. I couldn’t even keep them in their seats, let alone bring them up to grade-level standards.

I came to realize that I-and others like me who were part of an LAUSD program to turn educated professionals into instant teachers-never should have been allowed to take charge of a class without spending at least one year assisting someone who knew how to manage students. On the eve of graduating from our two-year, night-school training program, one bright, would-be teacher announced she was leaving to return to accounting. “I don’t really think I’m helping,” she said. Then she looked me in the eye and said, “Do you?”

So I think O’Connell is right on many counts, except that most teachers are better than I was. At the inner-city Los Angeles school where I worked, most teachers could manage a class like magic, plus decorate their rooms with word-rich illustrations. They were ideal role models, most of them first-generation college-educated Latinos who taught there because they cared about those kids-and the kids, by the way, were exceedingly bright. But year after year, the school received the lowest possible rating for its demographic.

Ancient Chinese Wisdom

Puzzling over this during one of my school breaks at LAUSD, I decided to go visit Castelar Street Elementary, a school in a Chinese neighborhood that continually received high test marks even though most of the students were English language learners from low-income families. The teachers were very good, but not better than those I had watched at my school, and their room decor was not nearly as attractive and print-rich.

I watched five different classes, then followed a mass of kids to the neighborhood library, where they studied in an upstairs workroom. The scene was not much different from any other homework hall, though there were parents and grandparents watching the kids. They couldn’t really help with the actual assignments, but watched patiently as the children worked, talked, and afterward ran around the library, annoying the other library patrons until closing time.

Perplexed as to how this made for high test scores, I walked outside and found myself nose to nose with a Chinese school, located almost next door, where many of these same students spent several hours on the weekend studying in Mandarin or Cantonese. Education was everywhere in this little slice of Chinese culture. As I asked random parents why they thought their school did better than others, it was also pointed out that Castelar offers tutoring on the weekends.

Santa Barbara has a Chinese school, too, begun in 1994 by UCSB Chinese lecturer Jennifer Hsu. On Sundays, about 80 children study Mandarin reading and writing for two hours, interspersed by an hour of arts like calligraphy and folk dancing. The teachers are mostly parents, and the administrators are all volunteers.

Hsu explained to me that Asian cultures have been studious for thousands of years. It goes all the way back to Confucius in China, who was part of a flowering of philosophical schools circa 500 BCE, around the time the Chinese started using chopsticks and developed their writing system. Confucius was not only a scholar, but a teacher of literature, history, art, music, sports. While many of the parents at the Santa Barbara Chinese School are successful engineers and professors from Taiwan, Confucius’ emphasis on education wasn’t just for the elite-it spread throughout the classes and the region, elevating the importance of a good education across China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and beyond. That explains a lot.

One Santa Barbara Chinese School parent-whose children are staggeringly accomplished in sports, music, and scholastics-emphasized the role of poverty as a major factor in low achievement. Although the mother has a degree, she stays at home in order to raise her children. How, she asks, can people do that if they are working all the time?

“If my kids had a choice,” she said, explaining that she makes her children schedule playtime in with their more studious activities, “they would rather go play outside with their friends than play piano. Any child would, but they have to discipline themselves. How can their family teach them this self-discipline if they are away from home working so much? The children go out to the streets to find a family feeling, and with a bunch of kids hanging out together with no adult supervision, guess what’s going to happen?”

Working-class struggles aside, the mother also pondered the cultural quandary, saying, “I don’t know how much the [Hispanic] cultures treasure education.”

Latino Futures

A popular idea in educational circles is to “raise expectations” for Latino students. Michael Gonzalez, who is the director of Compliance and Categoricals for the Santa Barbara School District, took umbrage when I used the phrase with regard to Latino parents, explaining, “I don’t think I’ve ever met, in my 35 yeas of working with students in Santa Barbara schools, two families-brown, black, white, or Asian-who don’t want the best life for their children.” But he conceded that a university education is not necessarily the goal of most Latino parents.

Even Gonzalez’s own parents never said a word to him about college. His father had a first-grade education and never worked fewer than three jobs, while his mother, with a high school education, was a stay-at-home mother. Gonzalez caught the education buzz from an English professor at Santa Barbara City College, Dr. Ronald Billingsly, an African American, who Gonzalez said “was knowledgeable, engaging, enthusiastic, literate, and phenomenally interesting, and who encouraged me.”

Now she is a UCSB sociology professor who teaches, reads, and writes about oral tradition.

Like Gonzalez, a lot of academically accomplished Latinos seem to have almost stumbled upon the path. UCSB sociology professor Mar-a Herrera-Sobek, who also has a degree in chemistry, lived alone with her grandparents in the agricultural fields of California because her parents had too many children to fit into their house. Not only did she hear her teachers’ message that school was a way out of hard labor, but she had little to distract her from reading. First District County Supervisor Salud Carbajal, who grew up in the heavily immigrant La Colonia neighborhood of Oxnard, credited his ineptness with household chores for his college education. Carbajal explained, “I remember my father saying to me, ‘Son, you’d better stay in school because you will starve to death if you have to be a laborer.'”

A number of educated Latinos in Santa Barbara are working hard to cultivate a culture of intellectualism within the community here that can sustain itself generation after generation. One of these is Marisela M¡rquez, president of La Casa de la Raza, which has always had an educational component among its broad range of social services. M¡rquez, who has a PhD in political science and a doctor and a lawyer for brothers, helped design the current after-school and summer offerings. During the past four years, these classes have focused on math and science using Mesoamerican culture-such as the Mayan pyramids and the Aztec calendar-as a basis. When considering the successful emphasis in Chinese schools on cultural arts, M¡rquez’s approach doesn’t seem so radical.

But Confucius’ teachings took about 1,000 years to grab hold of the Asian world, and much remains the same in Santa Barbara’s Latino culture as it was when Gonzalez was growing up. I recently ran into an Adams Elementary sixth-grader at a Westside Laundromat, and listened to her wax enthusiastic about school and share her desire to go to college in order to become a fashion designer. I asked her mother, who went through the fourth grade in Guatemala, if she wanted her daughter to go to college. “Yes,” said the mom, “because it is important to her.” The motivation for higher education, it seemed, was squarely on the sixth-grader. Another parent said her children, now grown, had felt the same way about school when they were young-but eventually school lost its charm.

It’s not that Latino families do not value school, said Denise Segura, another UCSB professor of sociology. Though they may not have ambitions beyond elementary or secondary school, parents revere the teachers almost too much, and take a hands-off approach to their children’s education. But even that may be changing.

For 21 years, Juanita Carney has been the principal of McKinley Elementary School on Loma Alta Drive, which has been in Program Improvement (PI) status for four years and risks being taken over by the state if test scores don’t improve. But the PI program also mandates district money be spent on tutoring, which is offered by a variety of for-profit and nonprofit companies that parents can sign up for during annual vendors’ fairs.

In 2005, McKinley got enough money to tutor 200 students. To generate interest among parents, Carney created coupons telling parents that their child was entitled to $1,200 worth of free tutorial services. Parents swarmed to the fair and all the available places were claimed.

“I personally feel,” said Carney, “that parents are much more aware now-whether it’s through the media they are listening to or the community grapevine-that they need to be involved in their children’s education. And I think there is an evolving awareness that, without a good, solid education, their children are not going to be able to have the kind of good life that they want for them.”

This September, the same kind of vendors’ fair was held at Santa Barbara Junior High School. The room was lined with representatives from tutorial companies all vying shamelessly to be chosen by the parents-some with their teenagers in tow-who crammed into the room the minute the door opened at 5 p.m. By the end of the hour, all the available spots were claimed. Two sets of parents who arrived shortly after 6 p.m. appeared close to tears as they asked if there was any possible way their students could participate.

The Value of Tutoring

This brings me to the main gripe I have with Jack O’Connell: His dream of reducing class sizes to 15 students, as daring as it sounds, does not go far enough. In my opinion, good, old-fashioned tutoring on a very personal level is the most reliable bet.

I was eventually eased out of the teaching profession when a federal grant at Isla Vista Elementary School dried up. The grant had funded the school’s tutoring program for English Language Learners that pulled them out of their classes in ever-changing groups for short periods of time at odd intervals. The program resembled a sleep disorder. But during my final year, I got to tutor a small group of English learners four days a week-the same six second-graders at the same time in the morning, for a whole hour.

It was heaven on earth. We just sat at a table together and read their grade-level literature over and over again, sometimes in exaggerated voices, sometimes timing ourselves. We also did phonics and even the occasional worksheet, though not as many as I was supposed to do. We chatted about literature and life. Nobody got ignored and I didn’t get into any fights with students. I don’t think I’m kidding myself when I say that a good time was had by all, and that the students learned to read and enjoy the written word.

Like my I.V. experience, the classes at the Santa Barbara Chinese School are small, with five to eight students per teacher. The 12 teachers, mostly parents, get paid $10-$14 per hour, but no one is in it for the money-once a parent’s children leave the school and move on to busy high school or college lives, the teacher/parent leaves, too. “It’s too much work, too much preparation, and very challenging,” said Hsu, the school’s founder.

"I don't know why we can't have this intensification in other areas," said Ah Tye.

When his daughter was at San Marcos High, Kirk Ah Tye, an attorney for the California Rural Assistance League, coached the Mock Trial Club. Although they were already some of the top kids at the school, Ah Tye said the club won the county competition because of the intimate tutoring they received. “The coaching is very intense, one-on-one,” he said. “The schedule was initially twice a week, and became almost daily or nightly as the competition approached. I’d like to see this intensification with the goal of college.”

So it’s not inexpensive or easy, but small-group tutoring is a proven method of elevating achievement. The National Institute for Science Education studied the effects of small-group instruction on university science, math, and engineering students. The students improved in “achievement, persistence, and attitudes” by a whopping 50 percent. Another small-group study on 122 very low achievers in kindergarten to third grade-some with aggressive discipline problems-also found a 50 percent improvement in reading ability, compared to a control group. But the improvement became substantial only after two years of that program, which corroborates an observation by the anonymous Santa Barbara Chinese School parent. “Sometimes I almost wish I could just stop raising my children and just let them go by themselves,” said the educated, stay-at-home mom, “but you can’t.”

Two more Santa Barbara elementary schools have hit Program Improvement status since 2005. That means the mandated money is more spread out, and only 55 students at each of the three eligible elementary campuses can receive free tutoring. For the secondary district, there is enough money for 66 students at each of the three PI campuses.

Student who do well academically seldom find themselves suspended from scool for discipline problems. Judging by the fact that 169 students were suspended last year from elementary schools, and almost 2,000 were suspended from the district’s junior and senior high schools, it appears that the number of students who need tutoring attention far exceeds the number who receive it.

It’s certainly true that intense, small-group teaching is expensive. But when you consider the consequences of the status quo, it begins to look like low-hanging fruit, and a bargain at any price.