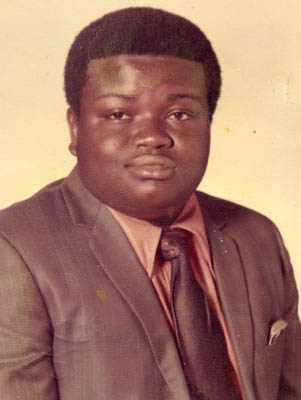

Rickey Ederington 1953-2007

Rickey Ederington was a gentle, gregarious African American and nine-year resident of the single-room occupancy (SRO) Faulding Hotel. He came to Santa Barbara 10 years ago for what was meant to be a simple day trip to sell magazines door-to-door, but ended up living here the rest of his life; a decade that was long on hardship and short on luck.

I met Rickey through an outreach project Trinity Episcopal Church sponsors at the Faulding-once a month, a group of parishioners brings lunch and some kind of creative activity to the hotel. The purpose of the project is to build a bridge with community members ordinarily dismissed because of their disability, poverty, or some other stigma. It was impossible not to love Rickey, with his larger-than-life personality, his good-natured kidding, and openness. Throughout time, we put together the pieces of his story, the events that led to his arrest in 1997 and the bandage taped conspicuously to his chest. After his death, I filled in the gaps by reading documents related to his failed claims against the city and county. It’s not a happy story.

Rickey was working for the Los Angeles branch of a national traveling sales company the day he arrived in Santa Barbara with a handful of other salesmen. He managed to sell a half-dozen subscriptions to homeowners on the Mesa, but on his way back to meet his group and return to L.A., he was detained by police and arrested for soliciting without a permit-an infraction. According to the notes of the arresting officer, because Rickey didn’t have good enough identification to be issued a citation, he was taken into custody and booked at the county jail. Despite his repeated statements to the officer that he was diabetic, and already late for his insulin shot, he was booked without being indentified as an insulin-dependent diabetic. He was kept there until his arraignment three days later, when his citation was dismissed. But according to his sworn affidavit, while in custody, he repeatedly asked for access to the insulin injections he desperately needed. The county denies withholding insulin from him, according to the case file, but Rickey’s sworn statements say jail personnel only gave him white pills; he was never told exactly what they were, only that they were to control his blood sugar. Still, they weren’t the injections of insulin he needed.

The dismissal of Rickey’s citation did not solve his problems; in fact, it was just the beginning. With skyrocketing blood sugar, he had to walk from the county jail to the police station to get his belongings. With no money to speak of, he got a room at the Rescue Mission. A nurse made an appointment for him at the county clinic where doctors told him what he already knew too well-that he needed coronary bypass surgery, and soon. Three months later, with his blood sugar more stable, Rickey had the surgery at Cottage Hospital. But in the weeks following, he developed a serious infection in the bone of his sternum. For the next 10 years-until his death on December 31-he would walk through the world with an open wound down the center of his chest.

Those who loved Rickey will always wonder how he managed, in the midst of all this, to summon his trademark charm and good will-it will remain one of life’s great mysteries. Perhaps it’s rooted in his Arkansas boyhood, where he was the second in a family with 10 children. What the Ederington home lacked in funds they made up for in kids. All but two were boys. Their home had only four rooms; the boys shared one, sleeping in a bank of bunk beds. Mr. Ederington was a physically powerful man who worked at the nearby International Paper mill making 50 dollars a week. Mrs. Ederington was a homemaker. If the weather was good, and he wasn’t working, Mr. Ederington would pile his brood in their truck-along with the lawn mower-and go fishing at Panther Lake, the lawn mower opening a path through the tall grass. Rickey’s younger brother, Carl, said their dad taught them all to cook early (Rickey’s culinary gifts and love of food were well-known around the Faulding). Every Sunday, one of the Ederington kids was tasked with making the family dinner while they were all at church, so it would be ready and waiting upon their return. This didn’t mean a holiday from religion for the appointed small chef. He or she would trot off to Bible study later in the afternoon. In high school, Rickey and Carl got after-school jobs at the nearby Duck Inn. When school let out at three, they’d run home and help clean the house. Then they’d go to work at the inn, where Rickey was a short-order cook and worked until midnight. But they got to keep their earnings.

After he started dialysis treatments a year or two ago, Rickey spent more time in his room. Perhaps he was trying to conserve his energy or avoid an infection. Whatever the case, in the week after Christmas, Rickey missed four dialysis treatments. Managers of the Faulding found him in his bed the morning of New Year’s Eve. He was holding his Bible.

Without a witness, there’s no way to know if Rickey’s arrest was racially motivated. He was certain it was-given the officer’s demeaning statements to him-but Rickey’s claims against the city and county were filed after the six-month statute of limitations was up, and the court denied his requests for leave to file late claims, even though he’d been struggling with serious health issues. If there’s anything to be learned from Rickey’s story, it’s one we already know but obviously can’t seem to change: It’s just not safe to be simultaneously poor and black, even in Santa Barbara.