UCSB Prof. Publishes Research on Man-Made Black Holes

Paper Touts Basic Physics Research, Refutes Fears About World Ending

If UCSB researcher Steven Giddings’ recent ideas about black hole creation on Earth are realized, then you might want to read this story fast, because those black holes could very well swallow up the planet. That’s what critics of the project, say, anyway, though Giddings would disagree that the research poses any threat to our existence.

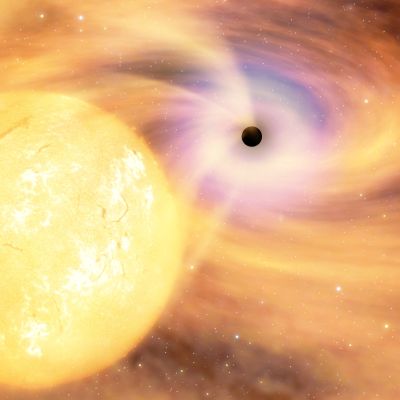

Giddings, a professor of physics, has coauthored a paper that has been accepted for publication in an upcoming issue of the scientific journal Physical Review D. The paper, “Astrophysical Implications of Hypothetical Stable TeV-scale Black Holes,” discusses his research on small, hypothetical black holes that would be produced by a machine called the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is being built in Geneva, Switzerland. The project, which will launch this September, has taken 14 years and has cost $8 billion.

The idea of black holes on Earth, however, has created some controversy, mostly due to the fear of the possibility that they might suck matter into them. According to a press release from the UCSB Office of Public Affairs, two men in Hawai’i have filed a federal lawsuit in hopes of stopping the startup of the LHC, citing apprehension about the safety of black holes.

However, Giddings has said that safety has been one of the researchers’ top priorities from the start.

“The future health of our planet and the safety of its people are of paramount concern to us all,” Giddings said in the press release. “There were already very strong physics arguments that there is no risk from hypothetical micro black holes, and we’ve provided additional arguments ruling out risk even under very bizarre hypotheses.”

In addition, Giddings said that despite his best hopes for the LHC, the possibility of it actually succeeding at creating black holes is very slight; but, if the researchers did end up producing one, the benefits would be vast. “Black hole production is not likely,” he said. “[But] on the off chance it did happen, it would be very exciting, and we’d learn a lot from it. There would be enormous consequences for our understanding of physical reality. Just discovering more dimensions of space would be a huge revolution in our understanding of nature : The LHC is exploring the next frontier of science, and is designed to help us understand the structure of matter, the properties of forces, and the nature of space and time at even shorter distances and higher energies than ever before,” he added.

According to Giddings, the LHC works by smashing several protons together at very high energies. “Occasionally,” he said, “when two of these protons collide, there is enough energy to temporarily produce new forms of matter, and possibly see effects of new kinds of forces beyond electromagnetism and gravity.” These new kinds of forces include black holes. “In some of our theories, there are extra dimensions of space,” Giddings said. “If the extra dimensions of space are configured in certain particular ways, it could be possible that black holes – or more properly quantum black holes – would be produced. This would happen when the proton collisions managed to focus enough energy into a very small region.”

Giddings said the value of this research is priceless, and will have an impact on technology of the future. “Look at history,” he said. “Much of what we have in modern society traces directly back to discoveries in fundamental physics in the past century or so. You wouldn’t have your cell phone, your iPod, your computer, or many other of the great benefits of technology without discoveries in fundamental physics : But when the original physics discoveries were first made, it was very hard for people to envision all their possible applications toward improving our lives,” he added. “That’s part of how basic research works. We drive toward deeper understanding, and ultimately that improves us in many ways.”

This story has been amended since its first posting.