DeSal Plant to Get Re-re-examination

Tuesday's Santa Barbara City Council Vote Is Not Enough to Prompt Study

It turns out the 3-2 council majority was not sufficient to authorize a $122,000 study of what’s required to fire up the City of Santa Barbara’s 18-year-old desalination plant. Because a four-vote majority is required for such a study, this week’s council “authorization” lacks legal authority, and the councilmembers will re-examine the issue this coming Tuesday. This past week, councilmembers Iya Falcone and Grant House were not present, so only five members of the seven-member body were on hand to vote.

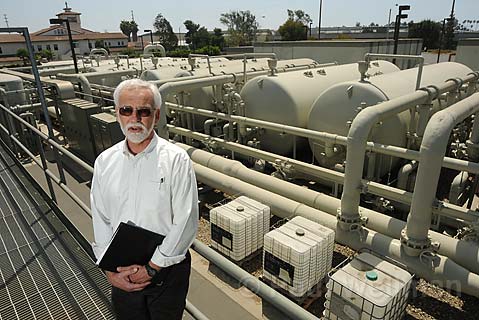

Water is one of those quintessentially Southern California topics that can’t be discussed without someone getting their hackles up, and the desalination plant – built in response to the sustained drought that afflicted the South Coast in the late 1980s and early ’90s – is no exception. Tuesday’s discussion was about whether to even study what would be required to get the plant – initially designed to provide water for the City of Santa Barbara, Goleta, and Montecito – operating again in case of emergencies. Water planners argued the study would provide solid information about how much it would cost to make the desal plant – on which City Hall spent $34 million in 1991 -operational, whether new technology might reduce the energy demand, and what kinds of permits might be required and from which government agencies. They also argued such information might prove useful as Santa Barbara prepares to revamp its general plan.

Councilmember Das Williams worried that a new water supply – the original desal plant was designed to produce 7,500 acre feet of water a year, more than half the city’s total water demand – would prove growth-inducing. He argued City Hall should spend its money studying water conservation, the long term effects of climate change, and how City Hall could further its water recycling efforts. And because desalination plants require an inordinate amount of energy, he fretted that the operation of the plant could wipe out substantial energy conservation gains City Hall has recently made. Finally, he contended that the ratepayers of Goleta and Montecito should not get a free ride since they might benefit from the operation of an emergency water supply.

Russell Ruiz, now with the City of Santa Barbara water commission and formerly the attorney for the Goleta Water District, is also concerned. In his written remarks, Ruiz explained that when the city enters its general plan update, it should be made absolutely clear that the desalination plan is regarded as a source of emergency water only. So long as the desal plant is regarded as a “baseline” source of water, Ruiz worried that other water agencies – plus influential state and federal water regulators – would regard the water capacity of the desal plant as a viable replacement for water the city now draws from Lake Cachuma. With the prospect of a prolonged drought on the horizon statewide, Ruiz’s caution is hardly academic.

Mayor Marty Blum argued that the cost of desalinated water was 25 times the price of its existing water and hence too expensive to fuel further growth. She said it would be “irresponsible” for the city not to find out what’s involved in re-activating the desal plant.

Councilmember Dale Francisco said such an emergency water supply could prove essential if the tunnels connecting city water customers with Santa Barbara’s two main reservoirs were to collapse in an earthquake. Without such a fallback plan, Francisco predicted, “There would be a lot of finger pointing and they would be pointing, justifiably, at us.” Williams noted that there were already plans afoot to build another set of tunnels – creating a “double-barrel effect” – as insurance in the case of an earthquake-induced tunnel collapse.

Aside from the desalination plant study, city water planners are preparing to bid for studies on the reliability of State Water, the long-term consequences of climate change on local water supplies, and the opportunities of further conservation and water recycling.

For the time being, the City of Santa Barbara enjoys a healthy and abundant supply of water, even though statewide, water planners are girding themselves for an onslaught of painful shortages. In that vein, the ordinance committee of the Santa Barbara City Council took the first baby steps toward passing a new landscape water conservation ordinance.

On top of all this, the council heard how last year’s Zaca Fire is still causing water quality issues for the city’s water supplies at Cachuma and Gibraltar. In response to all the silt and ash in the water, water engineers have been forced to dump large quantities of powdered carbon and other coagulants to fuse with the contaminants. But that creates large quantities of sludge, which has to be removed from the water and dried before it can be shipped off. Water engineers explained how they need to buy a belt-dryer to handle the sludge because there isn’t enough room to dry the sludge on the ground by the Cater Treatment Plant. To this end, the council approved the expenditure of $300,000 on a sludge belt.