Inside the Debate over What to Officially Call Fortified Red Dessert Wines

The Protection of Port

What’s in a name? If it’s Burgundy, Champagne, or Napa, it’s not just wine. It’s a place, too, and there is simply no argument about it. Thus, the names are rightfully protected from abuse by outsider profiteers.

But if we turn to port, the debate of who has rights to the word is less clear. While the so-named wine style is inarguably linked to Oporto, the Portuguese city on the sea downstream from the wine’s vineyards of origin, some winemakers feel that port is simply a generic wine style-not a product essentially linked to a specific place and terroir. Other regional names deserve protection, says winemaker David Hopkins of Bridlewood Winery near Los Olivos. Burgundy, for example, is a recognizable name that describes not so much a wine style as it describes its exclusive place of origin. But port, he argues, is a winemaker’s style that can be and is made virtually anywhere. Moreover, fortified red dessert wines, regardless of where they were made, depend upon the term “port” as a crucial point of marketing leverage.

“Is a consumer really going to understand me if I call it ‘a red fortified dessert wine, strengthened with brandy or some pot-distilled alcohol and ranging somewhere between 21 and 18.1 percent alcohol’?” asked Hopkins.

But as of March 2006, federal law has prohibited American winemakers from labeling their red fortified dessert wines “port” or even “port-style.” Labels that existed before the law was passed were allowed to remain in production, but new winemakers eager to make a port-style wine face a bit of a challenge. For example, Quady Winery in Madera County sells its port by the clever-and patented-name “Starboard.”

“The problem with port and sherry is that there are no other terms to describe them,” said Richard Gahagan, an industry consultant in wine labeling. “There’s not much you can do, except my favorite, ‘red oxidized dessert wine.'”

Rupert Symington, whose family has made and sold true port for 350 years in Portugal, believes the term deserves full protection. Douro port is unique in character, and imitating winemakers can sufficiently market their products with the terms “Ruby” and “Tawny,” he said.

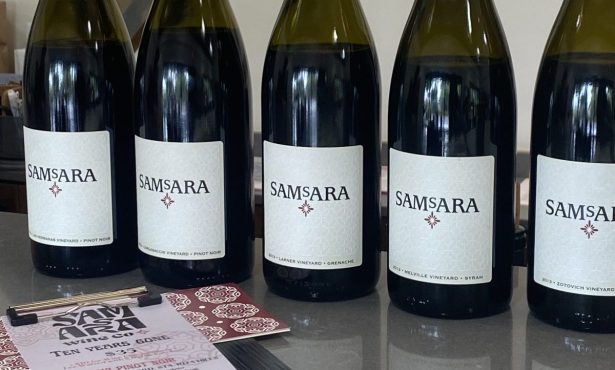

Kalyra Winery in the Santa Ynez Valley carries five Port-style wines, one of which is made with traditional Douro Valley grape varieties. Winery manager Martin Brown observes that more and more wineries throughout the state have elected to make sweet red wines and call them “port,” even if they are made through techniques that only vaguely resemble the traditional methods of port-making. In effect, he says, these wines are an abuse of the meaning of the term and tradition of port.

Yet port, Brown acknowledges, has become such a generic word that making it in new and innovative ways goes largely unquestioned. There are chocolate “ports” and mint “ports,” noted Brown. “You could even make a so-called ‘port’ by accident, if you get a stuck fermentation and high residual sugar.”

Portuguese ports are defined by a particular spectrum of grapes, a limited range of alcohol content, a specific aging scheme, and an appropriate fortifying liquor-not to mention a strictly delineated region of origin. Still, Kalyra does some innovating in making its ports. Its Gew¼rztraminer Port (white) and the 20-year Muscat Tawny Port each overstep the boundaries of what would be legal in the Douro River Valley. Each wine, however, received its current label years ago and so has persisted on the “grandfather” policy.

Although the red oxidized dessert wine of Bridlewood is made with estate syrah grapes, the wine is stylistically a port, says Hopkins, who has over 20 years of port-making experience under his belt. “If I can’t call this wine a port,” he asked, “then what do I call it?”

To him and others in America who model their red oxidized dessert wines after those of the Douro, if it looks like port, and it tastes like port, it must be port.