Prime Minister of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile to Speak in S.B.

The Future of Tibet

Eddie Izzard, British comic and star of the TV series The Riches, has a routine in which he discusses the English colonization of India. “You don’t have a flag?” the imaginary Brits ask the Indian people. “No flag, no country!”

That a country without a flag is no country at all is philosophically facile; in effect, however, it’s a point the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has successfully made about Tibet since the 1950s. The PRC officially has occupied the nation of Tibet since 1950 and unofficially ruled through regents since the 1700s; it has reduced Tibet to a government without a country at all.

But what both Izzard’s comedic Englishmen and the PRC conveniently ignore is the ability of a people to cling to ideals, to imagine a different future, and to hope beyond reason. The experience of a national identity is more important than a flag could ever be.

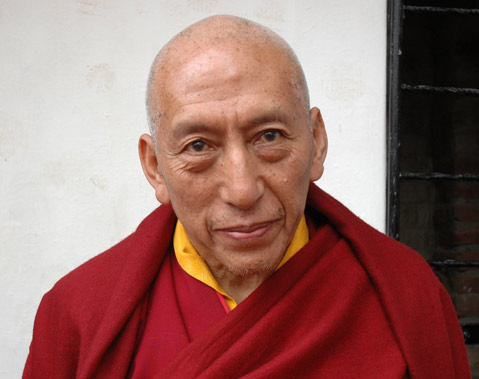

Samdhong Lobsang Tenzin Rinpoche, prime minister of Tibet’s exiled government, has devoted his life to keeping his people’s national identity alive. The fifth Samdhong Rinpoche was born Lobsang Tenzin in 1939, five years before he was recognized as the reincarnation of the fourth. At the age of seven he became a monk, and he has taught and promoted Tibetan interests ever since; he was voted into office by some 30,000 Tibetans in 2001. On October 20, he’ll appear in Santa Barbara at the Victoria Hall Theater to lecture on The Future of Tibet, which will discuss its future as a nation and as a political entity, a topic he is in a unique position to explicate.

China, of course, is the main obstacle. With a terrible human rights record-within the PRC as well as in occupied Tibet-China is handicapped in its relations with the Western world. At the same time, the United States needs a positive economic relationship with China, and has little to gain in promoting the interests of the Tibetan nationals. Samdhong Rinpoche, along with the Dalai Lama and other exiled Tibetan governmental figures, is thus left in an incredibly difficult position: China’s abuses are self-evident, but raising awareness of the plight of Tibet as a nation is the only option available.

The political viability of the Tibetan government-in-exile is also a large question, and one with no easy answer. Traditionally something of a theocracy, the nation of Tibet has produced figures of great importance to philosophy and religion. Both the Dalai Lama and Samdhong Rinpoche primarily are spiritual figures, teachers, and thinkers. While morals and philosophy are sound bases for a political theory, they’re not much of an asset in trying to negotiate international relations with China.

Further weakening the government-in-exile’s position is China’s refusal to admit its existence as a legitimate entity. In 2004, Tibetan officials sent a team of negotiators to Beijing; they were designated as “representatives of the Dalai Lama,” the only member of the Tibetan government the PRC would acknowledge. The necessity of making the negotiations nominally a personal act of the Dalai Lama caused some division within the Tibetan government itself, and further muddled the issue of who truly is responsible for Tibet’s future.

At the moment, the future of the physical land of Tibet would seem to be in the hands of the PRC, while the cultural and spiritual aspects of the nation are the responsibility not only of the Tibetan people under Chinese rule, but of the government-in-exile. Adjusting that balance of power in favor of the Tibetans is doubtless the future ideally envisioned by Samdhong Lobsang Tenzin Rinpoche.

4•1•1

Samdhong Lobsang Tenzin Rinpoche will speak at the Victoria Hall Theater (33 W. Victoria St.) on Monday, October 20, at 5:30 p.m. For tickets or more information, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.