Bristol: 100 at East/West Gallery

A Centennial Exhibition Celebrating the Life and Photography of Horace Bristol

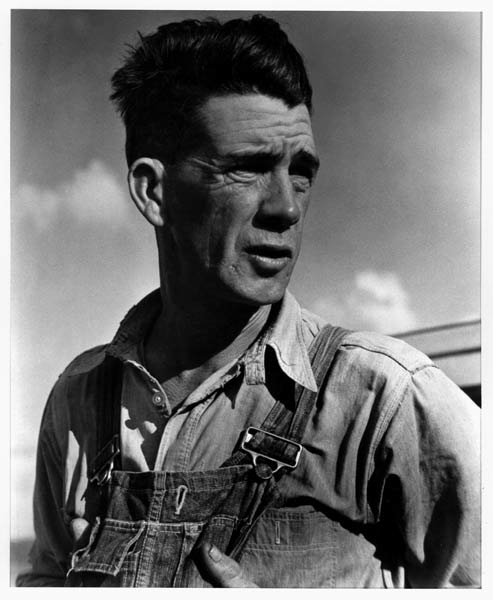

When gallerist Henri Bristol was assigned a book report in high school, he did what most kids would: brought home the novel in question to ask his father if he had ever heard of it. Upon seeing The Grapes of Wrath in his son’s hands, Horace Bristol disappeared to another room and returned with a selection of photographs that brought to life the characters and the setting of John Steinbeck’s epic California novel. The discovery of these photographs marked the beginning of a personal mission for Henri Bristol-to share his father’s images with the world.

“There was a huge part of his life that he had locked away,” Henri Bristol explained recently as he stood in the center of his Santa Barbara art gallery, surrounded by Horace’s work. In honor of what would have been his father’s 100th birthday, Bristol has put together a retrospective show, Horace Bristol: 100. “I knew he was a photographer ,and I had heard stories,” Bristol continued, “but I really knew nothing about his images until he started pulling them out after that incident in high school. I guess that’s why I feel this inexplicable link to his work.”

It turned out that the elder Bristol had been a staff photographer for LIFE magazine and in 1938 had worked closely with Steinbeck on a book-length project to document the migrant workers of California’s Central Valley. Steinbeck eventually pulled out of the project to write the novel that became The Grapes of Wrath, while Bristol’s hundreds of photographs went into the archives. It was in 2006, 20 years after he’d first seen those haunting, unforgettable images, when Henri opened East/West Gallery at 714 Bond Avenue, just one block from Santa Barbara Junior High.

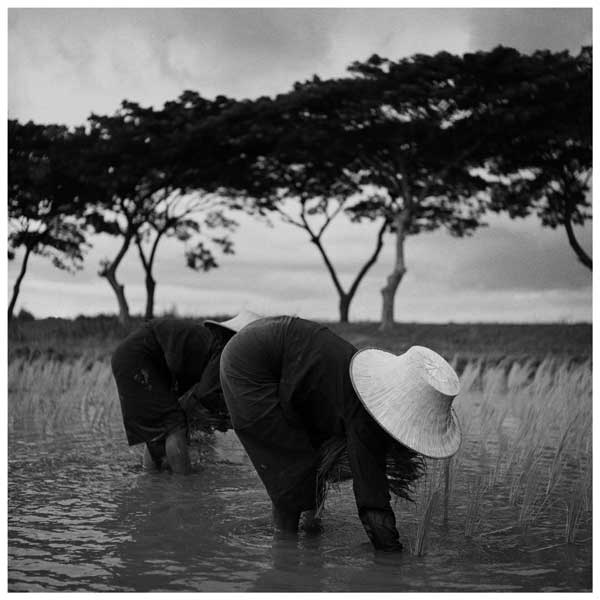

The name of the gallery is a nod to both his father’s California legacy and his ties to Asia. Horace Bristol spent a considerable portion of his professional career in Japan. He remarried and started a family with his Japanese wife there before relocating to Mexico in 1967-where Henri was born-and eventually returned to California in 1976. “The gallery’s name reflects my father’s East-West Photo Agency, a stock photography agency of sorts that allowed Western publications access to images of the emerging and developing countries of Southeast Asia,” Bristol explained. “The name also reflects the merging of Eastern and Western culture in my life and personal aesthetics.”

Horace Bristol was born into a newspaper family. Having ventured to Europe to study art and architecture in the late ’20s, he returned to Southern California in 1931 and attended a Los Angeles art school where he soon forged a connection with photography. Relocating to San Francisco two years later, he established a photography studio two doors down from Ansel Adams’s gallery and was soon keeping company with Adams, Edward Weston, and Imogen Cunningham. While many photographers of the time were dedicated to the pursuit of the medium’s aesthetic subtleties, Bristol stood firmly by his journalistic intent. Unlike his contemporaries, he rarely made singular images, leaning instead toward exposes. As the Great Depression descended upon the city, Bristol took his camera into the streets, and when LIFE magazine emerged in 1936, Bristol’s narrative approach was a perfect fit.

It was that same year when Bristol learned about the plight of migrant workers in California’s Central Valley, and teamed up with Steinbeck to document their story, a project that fizzled out. Bristol’s images remained in obscurity, Henri explained, “until the publication of the novel, when LIFE ironically published them to announce the book and later the movie. In fact, they cast the movie and designed the overall look of the film from my father’s photographs. The film has a very stark, documentary feel, and you can really see the connection.”

With the advent of WWII, Bristol joined the Navy’s Photographic Unit, where he found himself under the direction of one of his photographic inspirations, Edward Steichen. Here, Bristol employed the same empathetic approach that had guided his work at LIFE. By capturing the human face of war, Bristol quickly established himself as one of the leading practitioners of documentary photography.

At the conclusion of the war, Bristol moved his family to Japan and established the East-West Agency. But when, after 10 years in Asia, his first wife, Virginia, committed suicide, Bristol disassociated himself from the medium. He walked away from both the studio and photography-even destroying the negatives and prints he had at hand. It was a charged period of Bristol’s life; his time in Asia had contributed to some of his most insightful and poetic work before taking it all away.

“While it resulted in my dad locking away a portion of his life for a number of years, I think that the work he did in Asia is his real contribution to photography,” said Henri. “He lived there for 25 years and was able to tell so many stories. And he did so from such a unique perspective-he was right there in the midst of it and I really think this work is his ultimate legacy.”

4•1•1

Horace Bristol: 100 is on display at East/West Gallery through December 31. Works by Horace Bristol will also be shown at Brooks Institute’s Gallery 27 through December 1, with a reception on Thursday, November 6, from 5-8 p.m. For more on Bristol and the East/West exhibit, call 963-4041 or visit eastwest-gallery.com.