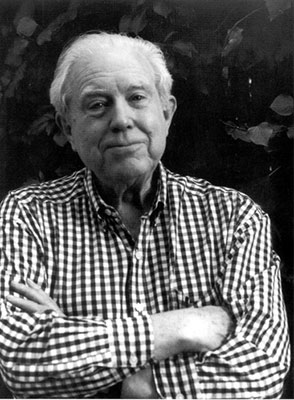

Elliott Carter Turns 100

Fringe Beat

A remarkable thing happened in America recently, although the news didn’t exactly light up mass media outlets. Elliott Carter, one of the indisputably great American composers in history, turned 100. The occasion was toasted with a Carnegie Hall concert, where the Boston Symphony performed Carter’s orchestral piece “Interventions,” written at age 98. He’s still actively involved in composing, and he wrestles and dances with the muse in a Greenwich Village apartment he has occupied since 1945. That kind of artistic continuity-and Carter is still going-is actually something brand new in American musical life.

Good luck finding Carter’s music on the radio or concert stage, especially on the West Coast. Last June at the traditionally anti-traditional Ojai Music Festival, a fine Carter chamber concert took place in the tiny Ojai Center for the Arts venue, as a rather gratuitous nod to his 100th b-day. If cultural justice were served, Carter-mania would have been center stage at the festival’s larger Libbey Bowl.

Part of the reason hats and hooters of the general public haven’t been flying relates to the supposed difficulty or intellectuality of Carter’s music. He tends to embrace dissonance and plot polyrhythmic pile-ups. But once you have gotten the language of Carter’s bustling musical conversations down, there is great visceral energy and hypnotic intrigue to be found. As with his compeer Pierre Boulez, Carter has wrangled expressive, muscular, and life-affirming spirit out of a presumably “dry” post-serial musical style.

In an interview in Los Angeles back in 1994-when he was a mere 85-Carter spoke expansively about his life in music. The story is often told that Carter’s musical awakening came, fittingly, after hearing Igor Stravinsky‘s pivotal Modernist masterpiece “Rite of Spring.” He explained, “I became interested in music through hearing the advanced music of the time when I was an adolescent in the late ’20s and early ’30s, when we did hear a lot of Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg and sometimes Charles Ives. I knew Edgard Varese quite well, and Charles Ives I knew somewhat. That music got me going in music. Then when I started to study at that time, most people who taught music were not interested in contemporary music and didn’t like the idea that a young man was starting out that way.”

Carter went on to study with famed pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, grounding himself in classical foundations. His music from the ’40s is lyrical and tonal, even Copland-esque. That early music actually does occasionally get played on classical radio (a cheater’s way for radio programmers to earn bragging rights, similar to playing Schoenberg’s pre-12-tone music). In those formative years, Carter said, “I felt I was learning how to write through writing this sort of neo-classical music, so finally I could write this more dissonant music that I really wanted to write from the very beginning.”

While recognizing that his music will never appeal to mass taste, Carter views his music as being directly engaged with the nature of life and human consciousness, in ways that other more simplistic and accessible music may not be. “What it’s all about really is the way we lead our human lives,” he commented. “There are all sorts of things: The way our attention is focused, and the way we deal with our problems. It seems to me that too much music has been too conventional in all of this. It isn’t a picture of living, somehow.

“I’ve tried to do that, to picture thinking and feeling. I’m not trying to be very high and transcendental about all of that, although the assumption is, of course, that human beings are wonderful things. They live this extraordinary thing that goes on. It’s rather hard to understand, but it’s also very remarkable.”

Try this: Create an “Elliott Carter” station on the current godsend to musical curiosity, Pandora.com. His music is much less scary than it’s cracked down to be. May Carter-mania spread: He is very likely the hippest centenarian in America.