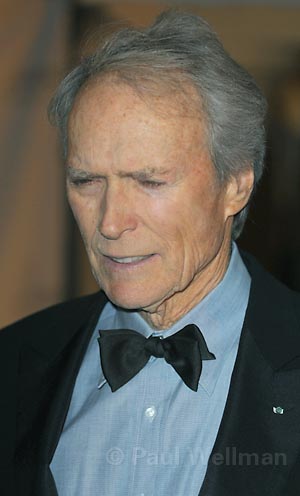

SBIFF ’09: The Good, the Bad, and the Arch-Conservative

A Look at Clint Eastwood's Aesthetic Life

If you’re reading this in newsprint, you’re probably old enough to have once considered Clint Eastwood a reactionary creep. “The action genre has always had a fascist potential,” said Pauline Kael, reviewing Dirty Harry in 1971. “And it surfaces in this movie.”

Remember, Eastwood emerged as what is now commonly called an “icon” in the late 1960s, leaping from his pungent television role as Rowdy Yates on Rawhide about the same time the core movie-going group was announcing the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. (I remember friends dropping acid to watch him in Sergio Leone movies, but that’s another story.) In a time of love and peace, decidedly antiwar at least, he was a man with no name and a long-pistolled cop who unapologetically used vigilante techniques to override a weak-kneed justice system-and, was applauded by the silent majority. To me, that man was a guilty pleasure at best.

He had fans from the beginning, though. Or at least after his dicey debuts in the 1955 “classics” Francis in the Navy and Revenge of the Creature. Between Leone’s glacially long close-up shots and Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry kill shots, Eastwood was something like the last of the craggy adventurers descended from John Wayne. (It’s telling that he first met Wayne in 1968 at the Republican convention.) But even those precious love-dominated years demanded Western heroes, and as the subsequent decades passed, Eastwood’s public stature grew as our tolerance for mayhem and escapism spread.

At first, his roles remained laconic-prone to shoot first and sort it out later. Walt Coogan, Private Kelly, and Josey Wales were not significantly different from each other and, though it seems blasphemous to say it, could’ve been played satisfactorily by Charles Bronson or James Coburn. Later, as he “grew” into comedic parts like Philo Beddoe in the chimp and trucker buddy movies like Every Which Way But Loose, his relationship with critics remained truculent, while his international mass popularity ballooned, even in the low Reagan-iffic eras when Heartbreak Ridge (1986) and Firefox (1982) redefined him as our frontline against the Evil Empire.

As a director, however, Eastwood’s critical estimation hardly ever suffered. He began directing right away, in fact-he claims to have stepped in for Leone, directing sequences of A Fistful of Dollars when the Italian auteur was ailing. But Eastwood’s first big splash was the nerve-rattling Play Misty for Me (1971). And though there are more than a few “meh” films among the 31 he’s made, very few of them are terrible. And some, mostly those made in the last two decades, have been astoundingly good-Unforgiven (1992), Mystic River (2003), and Million Dollar Baby (2004), most notably.

Only Woody Allen can claim anything like it for lifetime acting/directing output, and his hits are bigger, but his misses are, too. For sheer adventurousness, Eastwood can hardly be matched by any young director working-the two Iwo Jima movies were not great, but the impulse to take them on was. This last year’s output-Changeling and Gran Torino-brings him to an unmatched creative pitch. The only comparable directors are the Coens, who made No Country for Old Men and Burn After Reading back to back. But there are two of them.

And, yes, before applying the I-word yet again, let’s reiterate: There is only one icon named Eastwood. (He’s a refrain in an Adam Ant song, the title of a Gorillaz song, and a smirky character in Back to the Future III-his poncho and cigarillo ought to be trademarked.) But the streak of conservative values that helped to define him hasn’t disappeared as his directorial virtues have gotten more renowned. I always thought, much as I like it, that Unforgiven was a con job. Preach all you want about the wrongs of violence, but the film ends in a satisfying blood bath. Likewise, Mystic River concludes by asserting that might makes right and street justice prevails even among Boston’s lace curtain Irish.

And Gran Torino, well, don’t get me started. You can see it as a Shakespearean Tempest‘s Prospero-like conclusion to a career. Eastwood plays himself again (doesn’t he always?), a growling racist addicted to cutting down bullies. And it’s genuinely a funny film, which critics don’t often mention. But what’s with the Christ-like allegory at the end? His character Kowalski’s abnegated way of circumventing gangland revenges seems noble, but it wouldn’t have been necessary if he hadn’t started in on the Hmong street gang in the first place. So when he leaves the GT to Tao, Kowalski-and I have to assume Eastwood-is leaving a legacy of tough-minded resignation to the violence that lives on in America.

This would be Eastwood’s legacy, from the nameless stranger to the racist neighbor. Eastwood did not fit in with a hippie zeitgeist, obviously. And as much as I wish that peace could be given a chance in Eastwood’s ethos, I still respect the man, actor, and director for not only making five decades of movies completely consistent with his own philosophy, but because he made some of them great with craft.

He also made a fistful of dollars, but he never really sold himself out.

4•1•1

Clint Eastwood will be presented with the Modern Master Award on Thursday, January 29, at the Arlington Theatre.